- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: 'Thinking black'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'Thinking black'

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the wake of the Commonwealth parliament’s apology to the ‘stolen generations’, what are we to make of Daisy Bates (1859–1951) – especially given that, in the past year, two new biographical studies have appeared, indicating, more than fifty years after er death, an enduring fascination with her commitment to ‘render the passing of the Aborigines easier’?

Bates will not ( as Ann Standish hoped) ‘sink like a stone', taking with her with the easy popularisation of some of the most morally and politically debilitating characterisations of the 'plight' of indigenous Australians: that 'full bloods' are doomed to extinction because they cannot cope with 'civilisation'; that 'half-bloods' are, at best, the consequence of that failure, needing to be saved, or, at worst, evidence of irredeemable lasciviousness. 'The only good half-caste,' Bates once confided, 'is a dead one.'

- Book 1 Title: Daisy Bates

- Book 1 Subtitle: Grand Dame of the Desert

- Book 1 Biblio: NLA, $24.95 pb, 205 pp, 978064227544

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

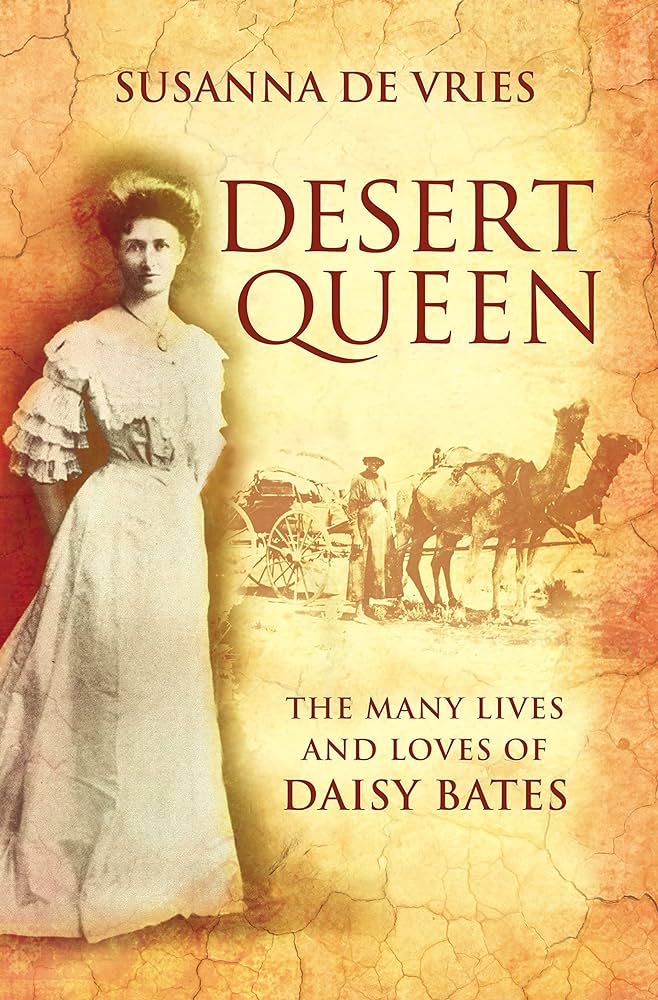

- Book 2 Title: Desert Queen

- Book 2 Subtitle: The Many Lives and Loves of Daisy Bates

- Book 2 Biblio: HarperCollins, $32.99 pb, 295 pp 978073228243

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Both Bob Reece and Susanna de Vries convey, in sometimes exasperated, often beguiled detail, the complexity of Bates’s personality, and the clever, pitiful twists of her life. She systematically lied about her family background, hiding origins in Irish Catholic poverty behind a genteel Protestant veil. A ‘terrible flirt’, so Reece observes, she contracted three marriages in two years (the last two bigamously) and may (de Vries speculates) have based much of her flaunted acquaintance with the British upper class on a period as ‘high class call girl’ at their weekend house parties.

Deeply opportunistic, Bates knew how to say and write the things that would please governments and editors – but not sufficiently so to gain security. In short, she could rarely be trusted until she committed herself to living with and recording the lives of ‘her natives’. Even then she was prone to sell yet another account of circumcision, infanticide and cannibalism if the need arose. But, fundamentally, de Vries insists, ‘she genuinely cared’ about the people with whom she lived at Eucla and Ooldea between 1912 and 1935. Her Passing of the Aborigines (1938) was, Reece maintains (a bit implausibly), ‘one of the most influential books ever to be published in the English Language’.

Such claims are challenging. How are we to understand such care and influence without straying too far into historical relativism? Each book has strengths in defining such boundaries. Neither offers a resolved assessment of their subjects as an historical figure.

Bates can’t be dismissed as an eccentric: she is too implicated – too much the ready apologist, sage, even celebrity. Reece’s book, which is based on Bates’s extensive papers in the National Library of Australia, demonstrates how much she was a part of the textual production of Aborigines in the first half of the last century, spanning from journalism to ‘scientific’ research. She even sought to write Aborigines into an environmental consciousness, but as those who had degraded the continent now presented to Europeans as a new chance and duty of development.

With her collection of Dickens ready to hand in her tent, and the piles of notes she struggled to keep from dust and disorder, Bates was part of a world of ‘literature’ that was, as Meaghan Morris argued, more inclusive, and elusive, than we now appreciate. Both Reece and de Vries give us Bates as an author struggling to be published, yet there is little sustained consideration of her writing as such – its style, appeal, models. We have her message but not her voice; its intention but not audience; her temperament (‘moody’. ‘difficult’) but not her tactics – that finely crafted intimacy she created as someone seen at the time to have learned ‘to think black’, yet who also recoiled in horror at many ‘ghastly’ practices.

Equally, for both authors, Bates is trapped in a fairly one-dimensional assessment of her zealously accumulated expertise. De Vries dismisses ‘amateur’ as a ‘misleading, modern construct’ in assessing Bates’s work, but argues just as trenchantly that Bates was denied the possibility of a ‘flourishing academic career’ as an ‘ethnologist’ or ‘anthropologist’ (‘depending on your point of view’). Daisy, she adds, has superior claims to Margaret Mead as the ‘pioneer of social anthropology’. For Reece, her interests were ‘scientific’ as much as journalistic, although he also notes a ‘subtle transition’ in her work from the ‘women of science’ to the ‘welfare worker who scribbled down information from her charges whenever the fleeting opportunity arose’.

‘Science’ and ‘anthropology’ are clunky terms with which to grasp the highly contextual nature of Bates’s work. As Isobel White judged, Bates was precocious in developing a ‘participant observation’ approach, living with communities, talking and watching at length, gaining trust. She has, to that extent, fair claim to be regarded as an anthropologist, especially in the period 1900—14. But to extrapolate from this a thwarted professional career seems to set aside much that drives these studies and accounts for Bates’s renown over the longer span of her life.

Prone to sneer at 'the hieroglyphics of the anthropologists', Bates s appeal and significance was, again, to another, wider world of commentary and interest. For Russell McGregor, for example, Bates belongs within a philanthropic strand of concern, her preoccupations with extinction to be contrasted with concepts of 'preservation' and 'uplift' in the work of Baldwin Spencer. Bates exemplified a 'sentimentally tragic' theme in thinking about Aborigines – a theme with its own genres, motifs, silences and complicity. Arguably it is one that we haven't quite escaped in our self-conscious, white rehearsals of sorrow and mourning.

It is within this theme – with its rituals of self-fashioning and self-regard – that Bates remains a relevant biographical subject. Inevitably, de Vries's is the fuller but more popular study. But in it detail comes at the cost of digressions ( do we need to be told that immigration ships of the 1880s lacked electric fans?), anachronisms (no 'hanky-panky' was allowed on such ships), howlers ('Catholic and Protestant National Schools' in Ireland; women barred from universities in Australia in 1883), cliches (relationships that would 'end in tears') and an author-as-sleuth style.

De Vries 's speculations about the sources of 'mystery money', the early onset of Bates's dementia, and her investigation of parallels with Lady Hester, Olive Pink and Ernestine Hill, are intriguing, but they leave us with a sense of a quirky individual more than they help us understand the circumstances of such choices, possibilities and performances. De Vries 's concluding personal note, that she commenced this study in search of her own concealed Irish origins, explains something of the legitimacy she confers to Bates, redeeming her as, in many ways in her time, a 'progressive humanitarian'.

Certainly, Bates emerges as no stereotype: she would not take charity for herself or 'her natives'; she sought to stop them making objects for trade, having, as Reece notes, 'no time for anything that was not absolutely authentic'. She is remembered in Down the Hole, a children's story by Edna Tantjingu Williams and Eileen Wani Wingfield, as swooping on Aboriginal children like a predatory bird, pursuing her obsession with eradicating the stain of miscegenation. Yet she also sheltered children from inspectors, and she is often remembered fondly by those among whom she lived. The starched and buttoned figure was likely, it seems, to linger longer than she should in applying olive oil, her sworn cure for venereal disease, to Aboriginal men. Taking all such evidence into account, Reece's final verdict is different: Bates exerted a 'retrograde influence' on popular thinking regarding Aborigines.

Which still leaves us with this enduring fascination for Daisy Bates. One theme spans the writing that has circled Bates. Julia Blackburn was steered towards Bates by an older acquaintance who recalled her desperate boredom in Australia between the wars – except for Bates: 'the only interesting person with a white skin who had ever lived in the entire continent'. Alan Moorehead's foreword to the 1966 edition of The Passing of the Aborigines similarly noted, 'she never for one moment in anything she said or did became a bore about them [the Aborigines]'.

Perhaps Bates is most important as an historical figure because she played adroitly on the sentimentality that conveniently surrounds Aborigines. She effectively personalised the romance of the primitive, the tedium of benevolence. 'Sorry', as Sara Ahmed warns, can get caught in a spiral in which 'the very claim to feel bad involves a self-perception of being good'. The figure of Bates might now at last prompt us to see both states as highly sentimentalised, self-regarding conditions, and finally lead white Australians to leave their tents.

Comments powered by CComment