- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: True Crime

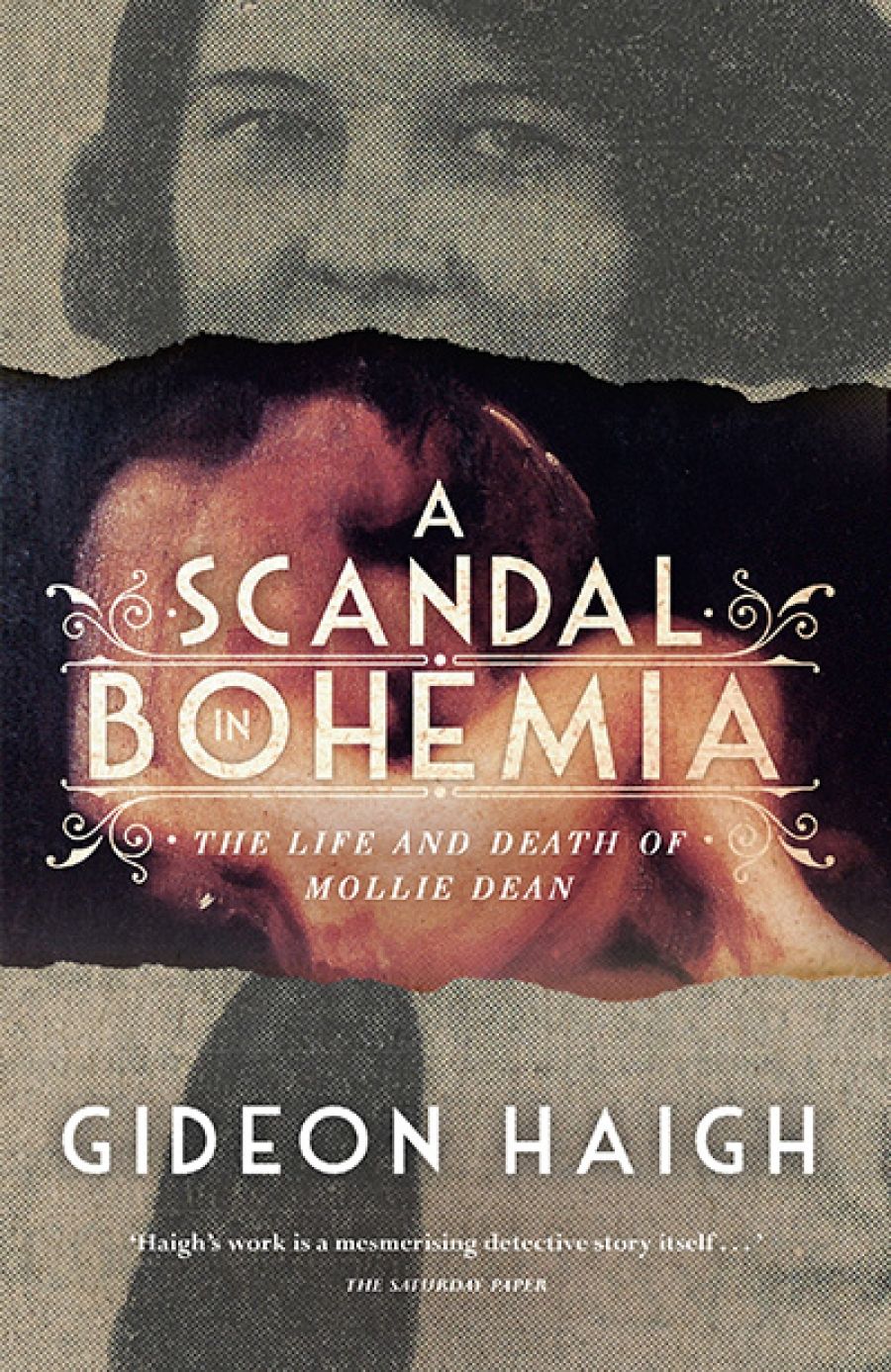

- Custom Article Title: Anna MacDonald reviews 'A Scandal in Bohemia: The life and death of Mollie Dean' by Gideon Haigh

- Custom Highlight Text:

A Scandal in Bohemia: The life and death of Mollie Dean is Gideon Haigh’s engrossing account of the circumstances surrounding the unsolved 1930 murder in Elwood of primary school teacher, aspiring journalist, and bohemian, Mollie Dean. Less true crime journalism than an interrogation of the genre, Haigh’s ...

- Book 1 Title: A Scandal in Bohemia

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and death of Mollie Dean

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $32.99 pb, 320 pp, 9780143789574

Haigh reflects upon the narrative effect of a crime that remains unsolved. ‘When nobody is punished,’ he writes, ‘the reproach distributes itself more widely, less predictably – over individuals, systems, societies, even the victim themselves, for incurring what can come to be felt as foreseeable danger. Instead of arcing, the narrative fans.’ Thus, Haigh’s narrative takes shape through powerful ‘layers of association’: between Mollie and Colahan, with whom she was in a relationship at the time of her death; between Colahan and George Johnston, via whose fictionalisation of Mollie’s murder, in My Brother Jack, many readers will first have encountered her story; between earlier representations of Mollie (in fiction, painting, diaries, newspaper reports) and Haigh’s own; and between Mollie’s death and the murders of other young women, past as well as present. As a result of this many-layered narrative, what gradually unfolds is as much a portrait of Mollie’s life and death as it is a portrayal of the city and the society in which she lived.

It is also the portrait of a woman whose story has remained disturbingly current. A Scandal in Bohemia is one among a number of recent retellings and in an especially satisfying chapter, Haigh considers these others – a play, Solitude in Blue (2002) by Melita Rowston, Lisa Miller’s ballad ‘Molly Dean’ (2016), and Katherine Kovacic’s forthcoming crime novel, The Portrait of Molly Dean – as part of ‘a belated female editing of [Mollie’s] story’. ‘[T]he times,’ writes Haigh, ‘rather suit Mollie Dean. She modernises so easily that it’s as though we have caught up with her rather than she catching up with us.’

Certainly, Mollie seems to have been an uncomfortable fit in many circles. She was, in this sense, ahead of her time. Mollie’s mother, Ethel Dean, chastised her violently for being ‘too brainy’, having aspirations inappropriate to her station, and mixing with ‘bohemians’. Indeed, the relationship between mother and daughter was so acrimonious that Ethel was suspected of being implicated in her murder. Neither were Mollie’s independence and creative ambition easily accepted by Colahan and his circle (the Meldrumites). They had their own – surprisingly conventional – ideas about what a woman’s role should be and how she should fulfil it. According to Haigh:

It was not only convention that Mollie found herself pitted against; it was unconvention too. To the ranks of the Meldrumites, she was a unique addition: young, bold and a bit barefaced, a misfit by gender, class and youth in being a woman who worked outside the home at a time it still in some circles engendered pity and contempt. Her manners were modern … It was thought of her that she had rather much to say for one so young … And for all their self-conscious épatage, the Meldrumites observed social conventions reflecting their leeriness of modernism. Women were fetchers, carriers and cleaners, and certainly not co-creators.

Mollie refused to accept such unnatural restraint. At the time of her death, she was writing a novel of which only the title, Monsters Not Men, remains. Her final act before walking home on the night of her death was to telephone Colahan to discuss the possibility of her giving up teaching in favour of pursuing a career in journalism. (Colahan was against the idea.) In the context of her refusal to comply, some of the contemporary responses to Mollie’s murder are all too familiar: that in seeking independence, she was also courting risk. When he heard of her violent death, Percy Leason is reported to have said, ‘How completely in character.’ And from Lena Skipper’s diaries – recovered years after the event from a rubbish heap at Montsalvat – there is a clear sense that ‘Mollie’s sauciness … was bound to drive a man to violence.’

At the heart of Haigh’s approach to Mollie Dean is a consideration of the ways in which, via narrative, we seek to make sense of a violent and apparently random act. In composing his narrative, he is, therefore, also concerned that it should tell ‘its own story’, which in the case of Mollie’s life – being ‘[t]oo brief to leave deep traces’ – leads ‘one unavoidably into … realms of [well-researched] conjecture’. Such conjecture pits itself against the suspect ‘closure’ of a ‘solved’ murder. In so doing, A Scandal in Bohemia focuses upon Mollie – in ‘the fullness of living’ – rather than restraining her story to the circumstances of a violent death.

Comments powered by CComment