- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

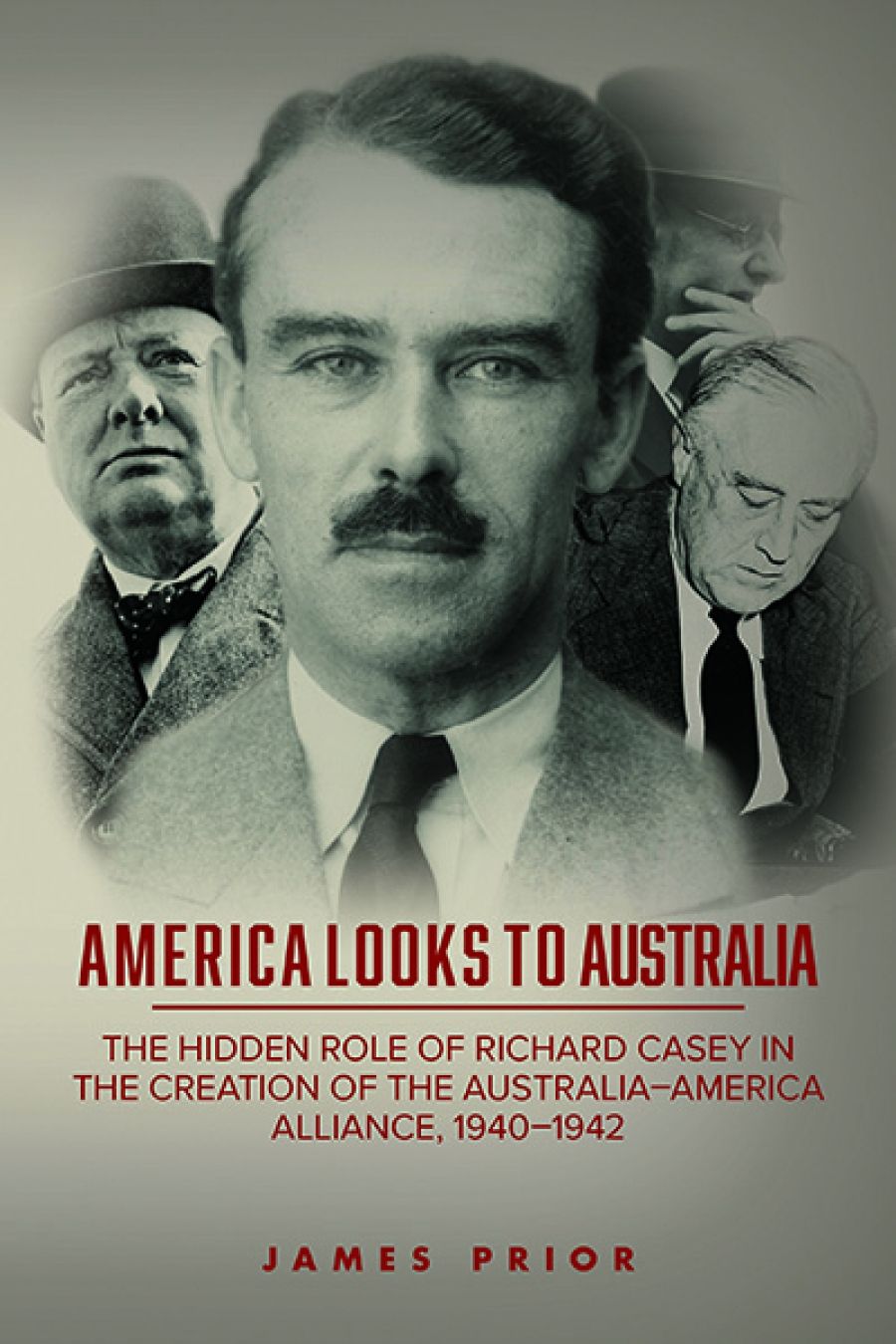

- Custom Article Title: Rémy Davison reviews 'America Looks to Australia: The hidden role of Richard Casey in the creation of the Australia–America alliance, 1940–1942' by James Prior

- Custom Highlight Text:

Duumvirates frequently dominate politics, irrespective of whether they are partners or rivals: Napoleon and Talleyrand; Nixon and Kissinger; Mao and Deng. But few second bananas survive history’s vicissitudes. A dwindling portion of the Australian public might still recognise the names of Robert Menzies and John Curtin ...

- Book 1 Title: America Looks to Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: The hidden role of Richard Casey in the creation of the Australia–America alliance, 1940–1942

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $39.95 pb, 244 pp, 9781925588323

As Prior notes, even prior to Federation Australian leaders recognised that Washington was a Pacific as well as Atlantic power, a fact the Spanish-American War (1898) made explicit. To drive the point home, Theodore Roosevelt’s ‘Great White Fleet’ circumnavigated the globe in 1907–09, visiting Melbourne and Sydney en route, demonstrating America’s burgeoning blue-water naval capabilities. The fleet’s visit was stage managed by Alfred Deakin, in an unsubtle cock of the snook to London. Britain’s alliance with Japan (1902–23) was unpopular with Australian political élites, as Tokyo was clearly a revisionist Pacific power, evidenced by its 1910 occupation of Korea. However, the 1922 Naval Treaty effectively gave Japan a free hand in the Pacific, deepening Australian anxieties still further, as Tokyo’s territorial aggrandisement in the 1930s went unchallenged by either London or Washington. Ironically, Casey greeted Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931 ‘with a sigh of relief’, convinced that Tokyo would be preoccupied by its northern turn, thus distracting it from adventurism in Australia’s immediate sphere of interest.

Casey was an early realist. Like his contemporary, the Sovietologist E.H. Carr, Casey was an enthusiastic appeaser, before the word took on pejorative connotations. Carr advocated appeasement of Hitler in his first edition of The Twenty Years’ Crisis (1939). In subsequent editions, Carr obliterated all references to his support for appeasement; however, for Casey, appeasement was a pragmatic means of averting a world war that was inimical to Australia’s national interests.

For Casey, British interests, a priori, were not Australian interests. London was a global power, but the European theatre was the epicentre of its core balance-of-power strategy. In contrast, Australian eyes were fixed firmly upon the Pacific. However, from the 1920s until 1935 Australia enjoyed little foreign policy autonomy; despite the 1931 Statute of Westminster, which conferred law-making powers upon the British colonies, Commonwealth policy remained entrenched at the Foreign Office. Energetic attempts by Stanley Bruce and, later, Joseph Lyons, to establish a system of diplomatic liaison officers were only partially successful; by the mid-1930s Australia still had no foreign service. Nevertheless, Prior finds Casey making early appearances in the diplomatic milieu of the 1920s; Casey acted as UK liaison officer throughout 1924– 1931, providing Australian cabinets with information that Westminster otherwise hid from its colonial governments.

Appeasers had gained the ascendancy in the late 1930s, counting Casey and Menzies among their numbers. Conversely, the ALP was isolationist, supporting a policy of withdrawal from international affairs. Menzies, leader of a minority government in 1939, argued that Poland was not worth fighting over, even after Hitler’s occupation of Czechoslovakia. The only noteworthy anti-appeasers were independent MP Percy Spender and that political polygamist, Billy Hughes.

Menzies may have considered himself British to the bootstraps, but geopolitics dictated a Pacific strategic calculus. In January 1940 he appointed Casey, his political rival, as Australia’s first ambassador to Washington. For Menzies, who was overturning his own earlier opposition to such appointments, worsening relations between London and Tokyo necessitated a decisive response. Cabinet also endorsed an Australian representative to Japan, but Rab Butler, an ultra-appeaser serving at the Foreign Office, intercepted Canberra’s request for an Australian minister in Tokyo and scotched the scheme. Butler thought an Australian legate would publicly reveal Canberra’s dissatisfaction with London and let slip to the Japanese that the colonies were far from united on foreign policy.

Casey deployed his considerable charm and networking skills to remarkable effect in Washington. Casey urged Canberra to gear up for war production; the means was American Lend-Lease, which prompted a wave of industrial dynamism in Australia. As US–Japanese relations reached their nadir in late 1941, Casey sought – and obtained – a guarantee from Washington, if the Japanese attacked Malaya. This was a singular achievement, which pre-dated Pearl Harbor. That said, Casey still sought to delay a Pacific conflict at all costs, although, like Churchill, he hoped an ‘incident’ would bring America into the war. He did not have to wait long.

Equally, it was Casey’s discussions with General George Marshall that likely persuaded Dwight D. Eisenhower and Franklin D. Roosevelt to designate Australia as Washington’s operational base to drive the Japanese out of Southeast Asia. By contrast, Curtin’s famous proclamation that ‘Australia looks to America’ was a diplomatic blunder that was condemned privately by Roosevelt himself. Elsewhere, Prior’s eye for detail impresses; one can only admire Casey’s chutzpah in attempting to set the Soviets against the Japanese in the wake of Pearl Harbor, if only to divert the Japanese from their southern push.

The shock of Pearl Harbor placed Casey squarely in Roosevelt’s circle and saw him appointed to Churchill’s war cabinet. Readers will not be surprised that Casey, as External Affairs Minister, ultimately oversaw the promulgation of the ANZUS Treaty in 1951. And, like his old boss, Curtin, Casey saw no need to include Britain in this new Pacific alliance.

Comments powered by CComment