- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Lyndon Megarrity reviews 'The Boy from Baradine' by Craig Emerson

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Boy from Baradine is one of the latest Australian political memoirs to hit the shelves. Craig Emerson, a prominent minister in the Rudd and Gillard governments between 2007 and 2013, has some interesting stories to tell about life as a political adviser, a pragmatic supporter of the environment, and an ambitious ...

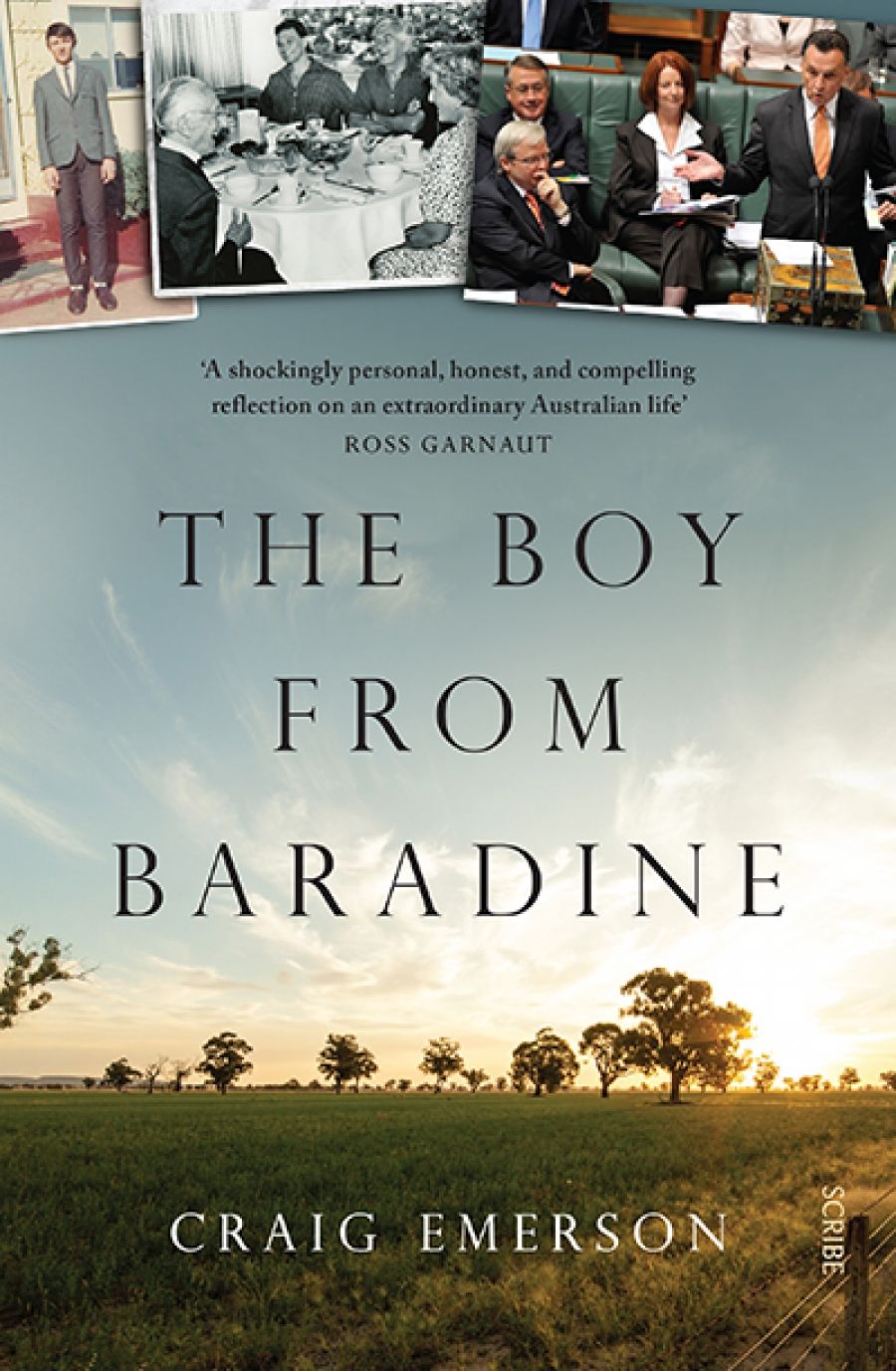

- Book 1 Title: The Boy from Baradine

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $35 pb, 368 pp, 9781925322590

Emerson studied economics at the University of Sydney and later completed a PhD thesis on mining taxation at the Australian National University. His supervisor, Ross Garnaut, was to be an important source of economic advice to the Hawke government. It was partly on Garnaut’s recommendation that Emerson became an economic adviser to Resources and Energy Minister Peter Walsh (1984–86), who was later promoted to Finance. Subsequently, Emerson became an Economic and Environmental Adviser to Prime Minister Bob Hawke (1986–90).

Emerson’s time as an adviser seems to have been the most enjoyable and rewarding of his professional life. ‘Hawkie’ knew how to have fun, and his staff loved him. According to Emerson’s account, part of Bob Hawke’s political longevity and reputation for being a good leader came from the prime minister’s capacity to listen to the uncompromising advice of his staff and from his ability to manage media and public perceptions. He was also able to form useful political relationships, not the least of which was with the environment movement. Emerson captures the excitement and passion of the Prime Minister’s Office as it achieved change on issues such as the protection of Antarctica from mining. Emerson shares a striking example of the camaraderie that existed within Hawke’s inner circle as they put the finishing touches to the 1987 election campaign song, with its chorus of ‘Let’s stick together; let’s see it through’:

Graham ‘Freudie’ Freudenberg improved the lyrics by replacing the second ‘let’s stick together’ with ‘Australians together’, his arm swishing in a theatrical loop, ‘Australians together; let’s see it through.’ With that flourish, Bob [Hawke], Singo [John Singleton], Terry [Hannigan], and staff sang the revised rendition with ever-increasing gusto … the air thick with Freudie’s cigarettes and Bob’s cigars.

Not all of Emerson’s anecdotes are so engaging. His memoirs of political staffers and others getting up to mischief and high jinks will leave most readers unmoved: for most of these stories to work you needed to be there at the time they took place and have a strong personal affection for the people involved.

Of greater interest to the general reader is Emerson’s account of climbing Labor’s greasy pole all the way to the ministry. To reach the top of politics involves an obsession with seizing the main chance, persuading powerful party patrons to use their influence on your behalf, and finding out that the friendship of fellow MPs can wither on the vine if you are perceived to be a threat to their own career ambitions. As Emerson’s own example shows, playing the political game involves personal sacrifices and challenges for any politician who wishes to maintain strong relationships outside work.

Emerson’s narrative of public life implies that the 24/7 political cycle and culture are not working for parliamentarians or for the people they are meant to serve. However, the author has little to say about how this cut-throat culture might be changed. He was personally advantaged and disadvantaged by a political world where being in the ‘right’ political faction or being associated with party heavyweights counted more that merit. Emerson does not use the memoir to challenge this modus operandi.

Nor does Emerson reflect in great depth on the immense public resistance to privatising government enterprises and other ALP reforms, other than to acknowledge its existence. There is an orthodox, doctrinaire quality to the author’s commitment to the free market and competition which means that his defence of Labor’s record tends towards the use of platitudes and slogans rather than illuminating argument: ‘This economic statement [of May 1988] … was pivotal in turning the nation away from an inward-looking Fortress Australia protected by high tariff walls to an open, competitive economy fully engaged with Asia.’

The Boy from Baradine is a conventional political memoir that is certainly better written and structured than many competing books of the genre. While the book has flaws, it is a useful contribution to our understanding of Australian political history since 1983.

Comments powered by CComment