- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

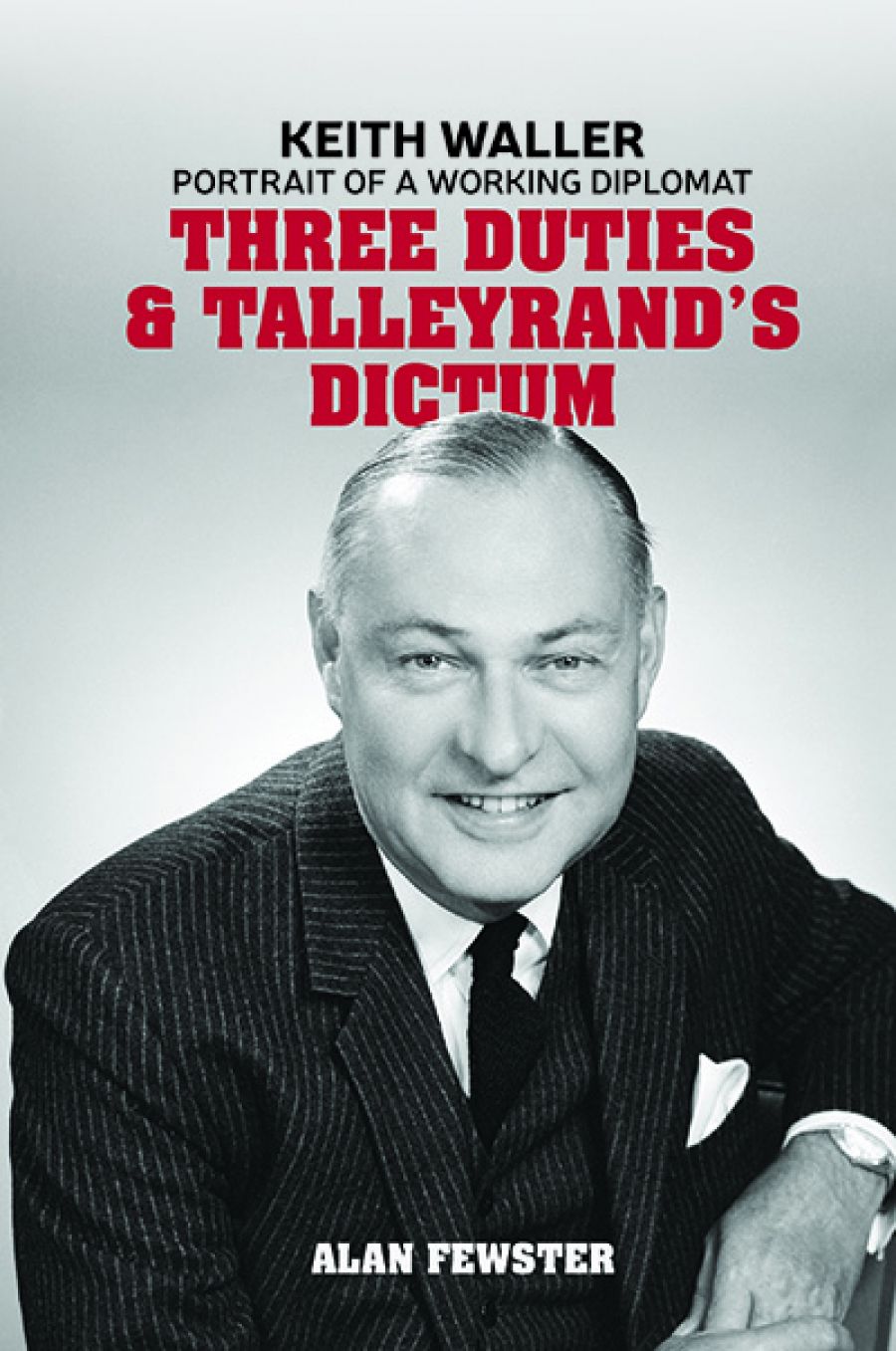

- Custom Article Title: Geoffrey Blainey reviews 'Three Duties and Talleyrand’s Dictum: Keith Waller: Portrait of a working diplomat' by Alan Fewster

- Custom Highlight Text:

Keith Waller was one of the top ambassadors in a period when Australia urgently needed them. During the Cold War, he served in Moscow and then Washington, where a skilled resident diplomat could be more important than a visiting prime minister ...

- Book 1 Title: Three Duties and Talleyrand’s Dictum:

- Book 1 Subtitle: Keith Waller: Portrait of a working diplomat

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $44 hb, 320 pp, 9781925588613

Accompanying the learned and kindly Frederic Eggleston, our first ambassador, Waller walked with some excitement up the steep hillside steps of Chongqing to meet China’s leader, General Chiang Kai-shek. The general’s wife, also present, was one of the four or five most famous women in the world, – charming in her ‘very hard way’, and admired by those who thought Nationalist China was a vital ally in the war against Japan. Young Waller was less impressed. He soon believed the ruling Chinese regime was corrupt, inefficient, and almost ready to be overthrown by Mao’s communists.

After China he served in Rio, Washington, and London, and then in Manila before becoming the ambassador in Bangkok, whose people he loved. Like apprentice tradesmen, he always learned on the job. Among his teachers was the long-dead Talleyrand of France, whose dictum embodied the advice, ‘Above all, not too much zeal.’ This was an injunction to be cautious and balanced.

Now and then Waller displayed zeal and passion. Wilfred Burchett was the first Westerner to describe the devastation at Hiroshima after the atomic bomb was dropped in 1945. Later, reporting on the Korean War as an intense sympathiser with China, Burchett was seen by the Menzies government as a traitor to the country of his birth, and he was refused an Australian passport. In response, Burchett, remembering that Waller had once been more or less his friend, renewed contact in Moscow where Waller became Australia’s ambassador in 1960. Ignoring Talleyrand’s dictum, Waller busied himself in an attempt to secure, from Canberra, passports for Burchett and his three foreign-born children.

In Washington as ambassador, Waller must have been a remarkable success. He had the ear of many powerful people: he diagnosed the military and political dilemma in Vietnam. Not so happy was the afternoon in July 1966 when he heard Harold Holt as prime minister depart for a few sentences from his typewritten speech and graciously say aloud – and off the cuff – to President Johnson that he was ‘all the way with LBJ’. Even Johnson shuddered a little when he heard Holt’s phrase, for he intuitively knew that in Australia it would be widely viewed as ‘going too far’. Waller heartily agreed: words were bullets and had to be chosen with care.

Seven years later, by chance, I sat with Waller on a federal committee. While breathing an air of authority, he seemed remote, as if he had done enough.

Alan Fewster has written a quietly impressive book. Continuing the tradition displayed by Peter Edwards in his well-known biography of Arthur Tange (2006) – another Canberra diplomat – Fewster’s book throws light on the rivalries and enmities of a variety of politicians and diplomats. As for Waller himself, he increasingly disliked H.V. Evatt, our foreign minister for most of the 1940s, and at times was wary of John Curtin, John Gorton, and Gough Whitlam.

Australia has produced at least a dozen civil servants who deserve a very high place in our history. Someday, monuments in their honour might well jostle and elbow the multiplying statues of footballers and cricketers in public parks. With his white handkerchief peeping out of his left suit-pocket, Waller will probably be a statue, for he served Australia from the eve of World War II to the height of the Cold War and advised, directly or indirectly, every prime minister from Joseph Lyons to Gough Whitlam, as well as fourteen foreign ministers.

Keith Waller died at the age of seventy-eight after languishing in nursing homes. His memorial service in Canberra in November 1992 drew little attention – Fewster could find no record of it. Of the capital city newspapers, perhaps only the Canberra Times published an obituary, and it was brief. The nation barely noticed the departure of its influential and loyal servant.

Comments powered by CComment