- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

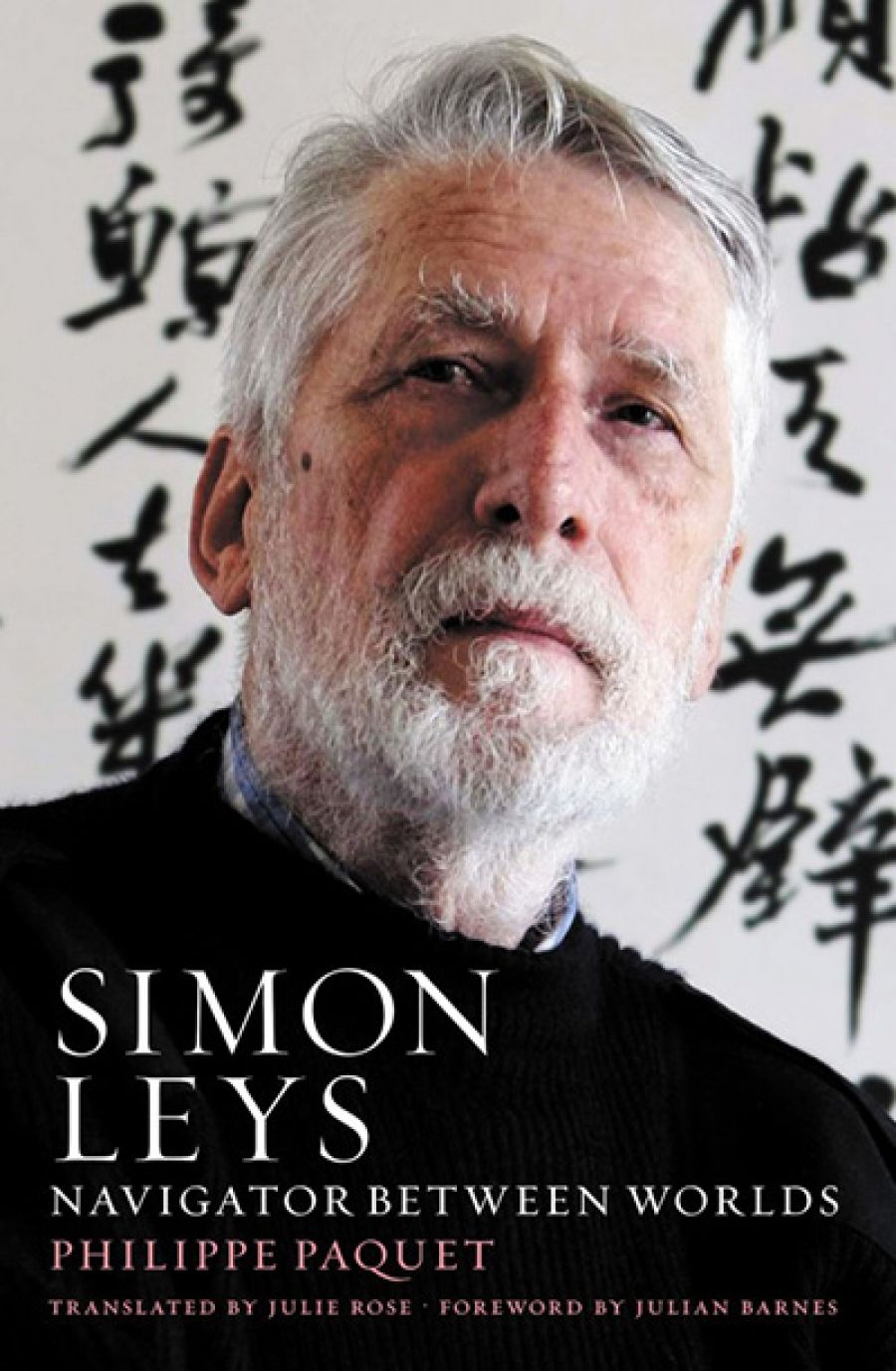

- Custom Article Title: Ian Donaldson reviews 'Simon Leys: Navigator between worlds' by Philippe Paquet, translated by Julie Rose

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Belgian-born scholar Pierre Ryckmans, more widely known to the world by his adopted name of Simon Leys, was widely hailed in the Australian press at his death in 2014 as ‘one of the most distinguished public intellectuals’ of his adopted country, where he had lived and taught for many years – first in Canberra, later in ...

- Book 1 Title: Simon Leys

- Book 1 Subtitle: Navigator between worlds

- Book 1 Biblio: La Trobe University Press (Black Inc.), $59.99 hb, 720 pp, 9781863959209

In his later years, Ryckmans was inclined to view the very idea of public usefulness – which he believed now dominated educational practice in Australia, prompting his own early departure from the academic world – with a certain gloom. He gave his own collected essays, published by Black Inc. in 2011, a title that teasingly posed an alternative view of the nature and value of learning. He called the collection The Hall of Uselessness. As a student (he explains in a foreword to the volume), he had lodged for a couple of years with an artist friend and two fellow students in a rundown quarter of Hong Kong, in a ramshackle building which the group adorned with a sign in fine calligraphic script proclaiming this house to be ‘The Hall of Uselessness’. Those who are young, those who are in any early season of learning – so a piece of traditional Chinese wisdom runs – are driven by love, curiosity, excitement, and pure indifference to ultimate returns: ‘In springtime the dragon is useless.’ Only time will tell if the years of learning have granted them anything of lasting value. ‘The superior utility of the university,’ as Ryckmans later rephrased this thought, ‘what enables it to perform its function – rests entirely upon what the world deems to be its uselessness.’

The longer trajectory of Ryckmans’s own years of learning is fascinatingly revealed – though at times overlaid by exhaustive detail – in Philippe Paquet’s comprehensive biography, first published in French in 2016 and now released in an English translation by Black Inc. and La Trobe University Press in their new joint publishing series.Ryckmans’s understanding of late twentieth-century China was slowly attained, as Paquet shows, through a series of journeys, observations, events, discoveries, and encounters, some planned or anticipated, others the product of chance or accident. An early visit to the Belgian Congo where his uncle (another Pierre Ryckmans) was serving as the country’s governor-general first alerted the younger Pierre to the humiliations and inequities of colonial rule, some of the worst features of which, as he later came to realise, were bizarrely replicated in Maoist China. A deeply exciting, month-long, first-time venture into China during his student years first stirred his ambition to master Chinese and acquire some knowledge of the country’s culture and history. ‘I discovered all at once that what we call “humanism” is just one humanism among others’, he later wrote of this visit,

and that the joy of encountering da Vinci or Mallarmé needed to be supplemented with the wonderment of discovering Leang K’ai or Li-Ho; and that there can be no genuine political awareness without awareness of the problems of Asia, and that the fate of the world of tomorrow seems to be linked to this prodigious awakening of China – which all Asia is watching closely.

Longer stays in Taipei, Peking, Singapore, Kyoto, and Hong Kong, along with frequent return visits to Europe and the United States, helped Ryckmans to refine these skills and adjust his view of events in China. In Hong Kong in 1967 he witnessed the gruesome assassination of the political satirist Lin Pin, burnt alive in his car together with his cousin (‘the first real political lesson of my life’). While in Bratislava the following year, he observed the violent suppression by Warsaw Pact troops of students and dissidents during the Prague Spring. Approached not long after these events in Hong Kong by Professor Liu Ts’un-yan of the ANU – ‘one of the last representatives of what was truly a generation of intellectual giants’, as Ryckmans later fondly recalled – Pierre and his wife, Hanfang, moved with their family to Canberra in 1970. ‘Coming to Australia is the best decision we ever made,’ he later said. ‘We could never have dreamt of anything better.’

Ryckmans’s wide and diversely acquired knowledge of China marked him off from those whom he wryly described as China ‘experts’, who lacked fluency in the language of the country they professed to observe and any deep understanding of its culture and history, and were content merely to repeat whatever their guides and interpreters (‘who take care of everything’) happened to tell them. He was shocked by the credulity of Western visitors to China such as Philippe Sollers and the distinguished members of his Tel Quel team, including Roland Barthes and Hannah Arendt, who appeared startlingly ignorant of atrocities occurring during Mao’s regime.

A keen linguist and confident speaker of Mandarin, Ryckmans gained his own knowledge of China in another way. While in Peking reporting for the Belgian Embassy, he journeyed regularly on foot or by bus or bicycle out into the countryside to meet with workers and local people and to hear their opinions. He loved and translated into French the autobiography of Shen Fu, a humble public servant in the reign of the Qianlong Emperor who, two hundred years earlier, had written of everyday provincial life in China in much the same quietly observant way that Ryckmans himself was now following. He drew on his knowledge of episodes in China’s and Europe’s history to throw partial light on current political events. Past and present realities – like those from the private and public sphere, like those vexed notions of ‘useless’ and ‘useful’ learning – were often (in his mind) surprisingly, unpredictably, and suggestively linked. Studying the story of the wreck of the Dutch trading vessel Batavia off the coast of Western Australia in 1629 and the conduct of the self-appointed leader of the community of survivors, Jeronimus Cornelisz, he found himself thinking of other more recent acts of political management.

Since, during the ‘Cultural Revolution’ seen from Hong Kong, I’d been able to watch Maoist totalitarianism in action from close up, this sudden overlap of two experiences in my life, ones that were totally foreign to each other but equally memorable – a passion for the sea and a horror of politics – gave me an irresistible desire to go and explore the story of the old shipwreck. I didn’t regret it.

(photograph by Ray Strange, Wikimedia Commons)

Ryckmans’s one brilliant venture into short fiction, The Death of Napoleon – conceived in the late 1960s, but not published until twenty years later – was already stirring somewhere in his mind as he worked on his longer study of another, later, exercise in tyranny, The Chairman’s New Clothes, published in French in 1971. Ryckmans aimed his critique of Mao from the far-left flank of the political field. He saw Mao as too conservative, too old-fashioned, too unyielding a figure to be trusted with rule of such a vast, diverse, and rapidly evolving country as twentieth-century China. Ryckmans’s distaste for the legacies of European colonialism inclined him firmly likewise towards the political left. But on questions of moral, religious, and social conduct his right-wing Catholic upbringing often continued to govern his views. He famously chastised Christopher Hitchens for his uncharitable writings about Mother Teresa, quarrelled publicly with former Governor-General Bill Hayden over his views on euthanasia, and failed to accept the case for same-sex marriage. Yet wherever you stood on such matters, Ryckmans’s views – expressed with a lacerating wit and brilliant economy (qualities not always achieved, alas, in this otherwise meticulous study of his life) – were likely to make you pause for a bit in your own opinions, and smile at moments at his sheer dialectical skill.

That these were the effects also of his teaching is clear from the testimony of his former students, one of whom, Kevin Rudd, has recently written of Ryckmans’s loving demonstrations of the art of calligraphy, energetic singing of Chinese revolutionary songs – an exercise in parody, as Rudd eventually realised – and, on the lawns outside the ANU’s Asian Studies building, of Chinese shadow boxing. Was this useful or useless learning? Who can tell? It gave Rudd delight and directed his vision – like that of no other Australian Prime Minister before or after him – unerringly towards China. ‘Canberra was not quite big enough to cope with the prodigious mind, talents, and broad-ranging scholarship of Pierre Ryckmans,’ writes Rudd. ‘He was one of the finest intellectuals Australia has ever welcomed to its shores.’ Philippe Paquet’s study of his friend and fellow-countryman’s life and achievements, completed shortly before Ryckmans’s death, confirms and endorses this affectionate verdict.

Comments powered by CComment