- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Custom Article Title: Anwen Crawford reviews 'Sticky Fingers: The life and times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone magazine' by Joe Hagan

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sometime in 1970, an unidentified person – perhaps a disgruntled journalist or aggrieved interviewee – scrawled the words ‘Smash “Hip” Capitalism’ onto an office wall at Rolling Stone magazine. It was an incisive piece of graffiti. Rolling Stone had begun publishing in 1967, in San Francisco, at the epicentre of the ...

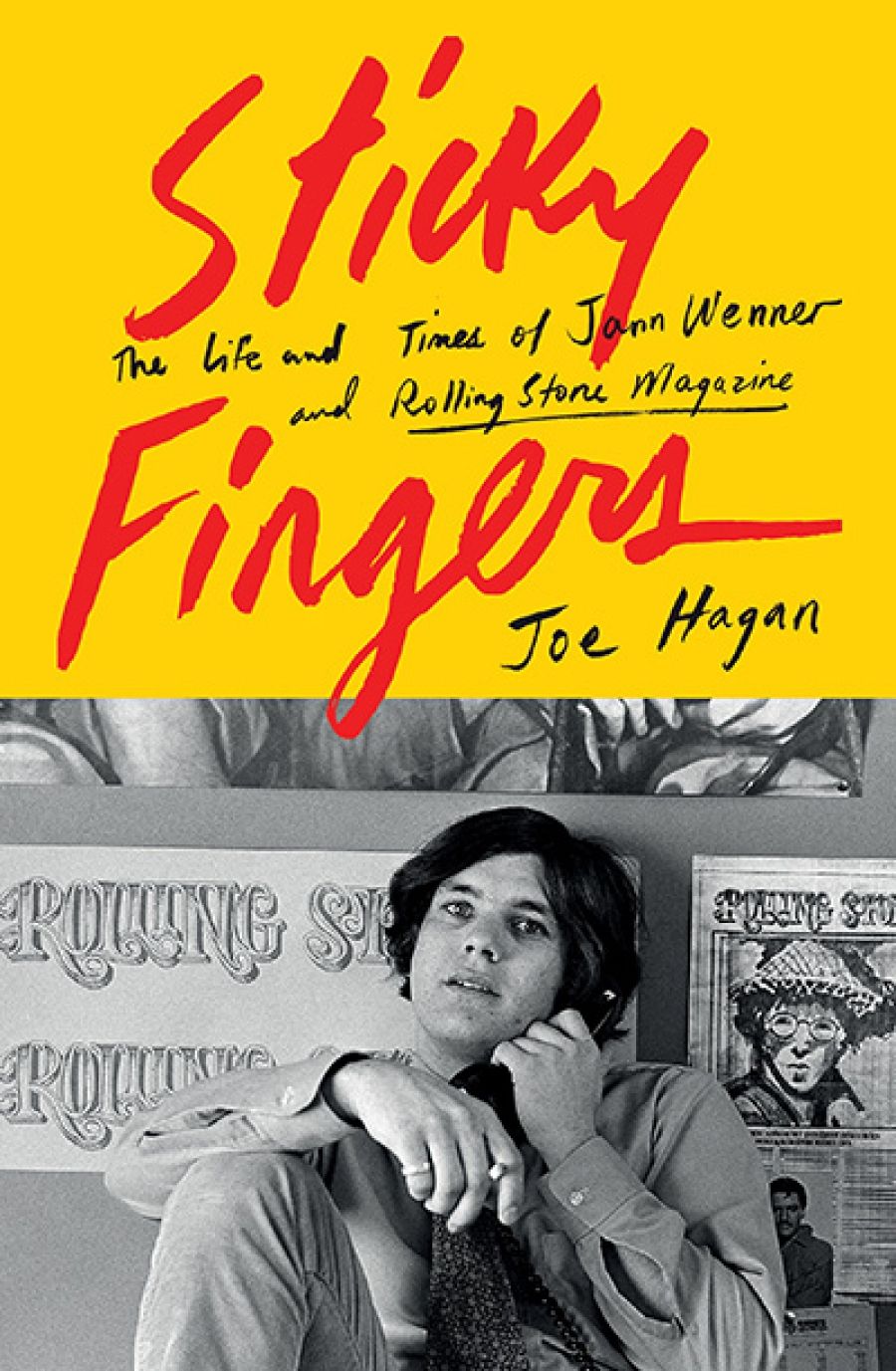

- Book 1 Title: Sticky Fingers

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone magazine

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $34.99 pb, 457 pp, 9780670078653

Rolling Stone would become not only a corporation, but an American cultural institution. It would usher in the gonzo journalism of writer Hunter S. Thompson and the celebrity portraiture of photographer Annie Leibowitz, among other famous bylines. Wenner, a man of limited critical acumen and average journalistic skill, may have only had ‘one great idea’, writes his biographer, Joe Hagan, but it was an idea with staying power. Wenner realised, sooner than just about any of his peers, that the legacy of the 1960s could be turned into a business. He used Rolling Stone in order to shape what is now the canonical version of popular music history, with The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan as its Holy Trinity. Unquenchable nostalgia for the 1960s would make Wenner spectacularly rich. It would not make him loved.

Sticky Fingers is the first authorised biography of Wenner, and it is far from flattering. Wenner has never met a friend – or an enemy – he couldn’t somehow use, and those who have suffered his betrayal speak bitterly. Dozens of soured relationships and broken promises run through the pages of Hagan’s book, and nearly everybody, from former Rolling Stone colleagues to rock stars to family members, has chosen to speak on the record. Perhaps Wenner, who has spent the better part of half a century coming out on top, believed that co-operating with Hagan, an experienced New York journalist, would ultimately be to his advantage. A firm believer in his own historical importance, Wenner has held onto copies of just about every memo and letter he’s ever drafted, and Hagan was granted access to this exhaustive personal archive. The result of that research, combined with Hagan’s interviews, is a detailed but unlovely portrait of an ambitious, needy, often conflicted man, and the gilded circles he has moved in.

‘The first child of the baby boom’, Wenner was the eldest son of parents keen to disguise their European Jewish roots (the family name was changed from Weiner) and to assimilate into an affluent, suburban, postwar California. From a young age, Wenner possessed an unassailable ego. When he took over the student newspaper at his private Los Angeles high school, he was quick to discover that he could accrue both attention and social status as a publisher. He was an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley during the Free Speech Movement of 1964–65, and reported on those protests for NBC News. Like most of his fellow middle-class students, he avoided being drafted to fight in Vietnam (‘None of my friends died there’).

Jann and Jane Wenner, 1970 (photograph by Robert Altman)

Jann and Jane Wenner, 1970 (photograph by Robert Altman)

Wenner, by his own admission, ‘was not a deep musical person’ – he never saw The Beatles in concert – but he was nevertheless taken under the wing of experienced West Coast music critic and jazz fanatic Ralph Gleason, who admired the younger man’s ambition. In 1967, Wenner went to Gleason with an idea to start a newspaper in the vein of Britain’s Melody Maker, ‘but an American one that would be different and better’, covering not just music but the whole gamut of the counterculture, including plenty of sex and drugs. Rolling Stone was born.

Hagan has a clear eye for Wenner’s essential conservatism. Despite the thin veneer of countercultural rebellion that Wenner cultivated in the pages of Rolling Stone, the magazine would court a suburban readership, and it would sell to these readers the usual mass market products: cigarettes, alcohol, and cars. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s – Rolling Stone’s most successful decades – its cover stars skewed heavily white and male (Jackson Browne, Bruce Springsteen, Mick Jagger endlessly). Joni Mitchell was dismissed as ‘vanilla-voiced’ and Janis Joplin mocked as an ‘imperious whore’. Michael Jackson was denied a Rolling Stone cover even when 1982’s Thriller made him the biggest pop star in the world, because, according to Wenner, the magazine didn’t do ‘R&B acts’. Punk, hip hop, MTV, and the internet: Wenner considered each of these things as passing fads, and was repeatedly proved wrong.

Jann Wenner (photograph by Kevin Fitzsimons, Flickr)

Jann Wenner (photograph by Kevin Fitzsimons, Flickr)

Despite the occasional moment of pat scene-setting (‘He flicked on the television. John Lennon was dead’), Hagan’s biography is, on the whole, lively and nuanced. His subject is a difficult man, but Hagan doesn’t stoop to a hatchet job. Wenner sold his remaining fifty-one per cent ownership stake in Rolling Stone last year; the internet extinguished the magazine’s cultural clout. But Wenner remains ‘the de facto architect of rock’s cosmology’.

Comments powered by CComment