- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Gregory Day reviews 'Incredible Floridas' by Stephen Orr

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Despite the detailed excavatory art of the finest biographies, sometimes it takes the alchemical power of fiction to approximate the emotional geography of a single human and his or her milieu. Stephen Orr’s seventh novel, a compelling and at times distressing portrait of a twentieth-century Australian painter and his family ...

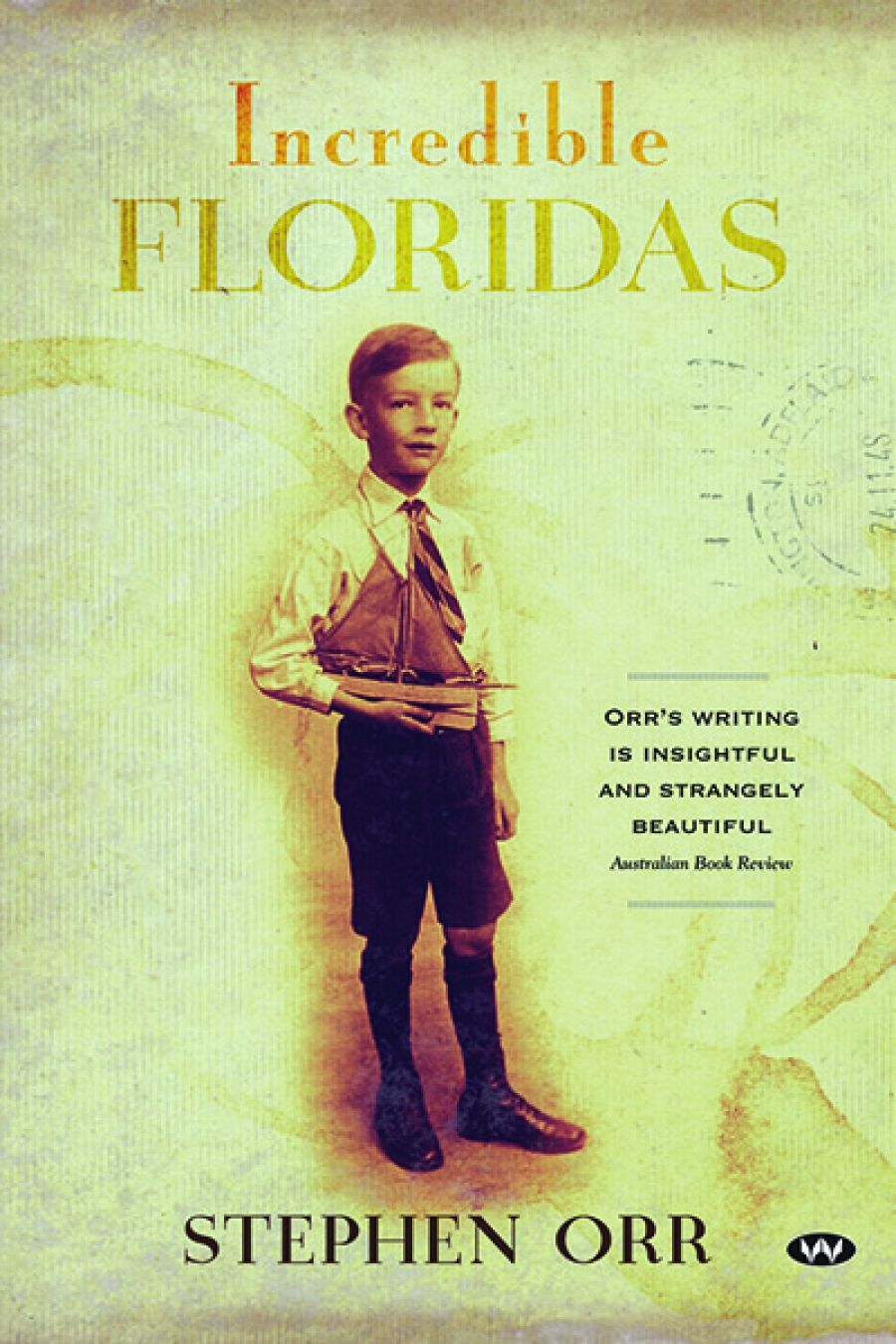

- Book 1 Title: Incredible Floridas

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $32.95 pb, 335 pp, 9781743055076

As the novel’s action opens in 1962, Roland Griffin is a nationally revered painter, an artist whose vernacular imagination has triumphed in England and whose daily routines in the studio represent the complex heart of the novel’s mise en scène. For the artist’s son, Hal, his father’s fame, and perhaps most particularly the charismatic singularity of his ongoing artistic practice, seem to have created a destabilising effect. Or perhaps it is not that simple. The non-linear construction of the novel, as well as its intrinsic empathy, helps to keep such easy conclusions in flux. Orr’s artist, for instance, does not exhibit a stereotypically destructive or dark obsession, but rather a way of being that subtly constellates all those living around it.

Orr’s longstanding interest in family dynamics comes to the fore in Incredible Floridas as he orchestrates the cross current of energies of what is both a completely ordinary Australian family and one with a significantly contrasting element. There is a ‘great man’ in their midst, one whose gift it is to fashion an authentic yet emblematic reality out of the scrappy and often inchoate material of the primary world. What the events of the novel imply is that no matter how good-natured or balanced this artist may be his very vocation can unintentionally detonate a molten atmosphere among those closest to him. In the case of the Griffins, it is Hal who both scorches and is scorched.

But of course it could never be just Hal alone. Not in such a tight-knit family and community. In the course of the boy’s teenage years, everyone is caught in the web of his radical destructiveness: his mother, his sister, his neighbours and close family friends, all of them, through compassion and affection, trying to sort out the mysterious and inexplicable material that lies at the heart of Hal’s troubles.

The matrix of this wider family group is a compelling element of the novel. Orr’s characterisations are affecting and he works well with the mid-twentieth-century vernacular textures of a lost Adelaide, painting a layered and sensory family picture reminiscent of George Johnston’s Melbourne or Christina Stead’s Sydney. The destructive misogyny of the time is clearly represented here too, as the emotional intelligence of Hal’s mother, Ena, is constantly dismissed as needlessly anxious by both father and son. Hal’s heartless mistreatment of women his own age has catastrophic effects.

Stephen Orr (photograp by Philip Martin)Orr also renders the way in which the creative nuances of Griffin’s art jostle with the often monosyllabic and knockabout attitudes around him. The novel contains a valuably unsettling record of what could be described as ‘the grammar of the unsaid’ in Australia at that time. There is a constant sense of Griffin and others extemporising their way through the more difficult terrain of their lives, hoping for the best, following ‘she’ll be right’ hunches and relying on the kind of chancy intuition the artist might call upon in his paintings. Everyone seems to mean well – except Hal perhaps – but there are large and musty shadows which no clarifying light ever reaches into, so that a sense of craftlessness pervades the characters’ repeated attempts at redirecting Hal’s plight.

Stephen Orr (photograp by Philip Martin)Orr also renders the way in which the creative nuances of Griffin’s art jostle with the often monosyllabic and knockabout attitudes around him. The novel contains a valuably unsettling record of what could be described as ‘the grammar of the unsaid’ in Australia at that time. There is a constant sense of Griffin and others extemporising their way through the more difficult terrain of their lives, hoping for the best, following ‘she’ll be right’ hunches and relying on the kind of chancy intuition the artist might call upon in his paintings. Everyone seems to mean well – except Hal perhaps – but there are large and musty shadows which no clarifying light ever reaches into, so that a sense of craftlessness pervades the characters’ repeated attempts at redirecting Hal’s plight.

One of Orr’s main achievements then is to interrogate the external textures of mid-twentieth-century Australian life – the sleep-out, the smell of a roast, the constant patina of nostalgia and sentiment – with a starkly delineated interior realism. There is one painting that the artist cannot finish, one that remains unresolved, that of a boy in a boat, the artist’s Rimbaudesque portrait of his own son. Despite the undoubted and even symbiotic emotion Griffin feels for Hal, and despite all his inklings regarding what might heal him, there remains the conundrum of the son’s very self being constantly subject to the artist–father’s all-consuming imagination. ‘This is about my son. Hal Griffin, boy, climber, jam-maker, letter-writer, little sod, miracle,’ Griffin says at one point. But ‘little sod’ comes nowhere near to naming the complexity of the wilful damage Hal inflicts, and the miracle he needs is never accomplished. In his moments of clarity, Hal knows this too. In one telling scene during a road trip into the far north, he clumsily fires a shot at a crocodile and his father comes running in fear. ‘I heard the shot,’ Roland gasps. But Hal is sceptical. In the instinctive intensity of the moment, it is impossible for him to separate his father’s concern from his artistic self-interest. ‘You couldn’t paint a corpse,’ he thinks, bitterly. It is both a transitory and indelible insight, and one which lies at the very heart of the novel.

Comments powered by CComment