- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Paul Genoni reviews 'The Drover's Wife' edited by Frank Moorhouse

- Custom Highlight Text:

In this collection of more than thirty pieces of fiction, journalism, criticism, academic papers, and ephemera (acceptance speeches, parliamentary questions, university course outlines), Frank Moorhouse gives evidence of, and attempts to explain, the durability of Henry Lawson’s classic short story ‘The Drover’s Wife’ in ...

- Book 1 Title: The Drover's Wife

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, $34.99 hb, 381 pp, 9780143784821

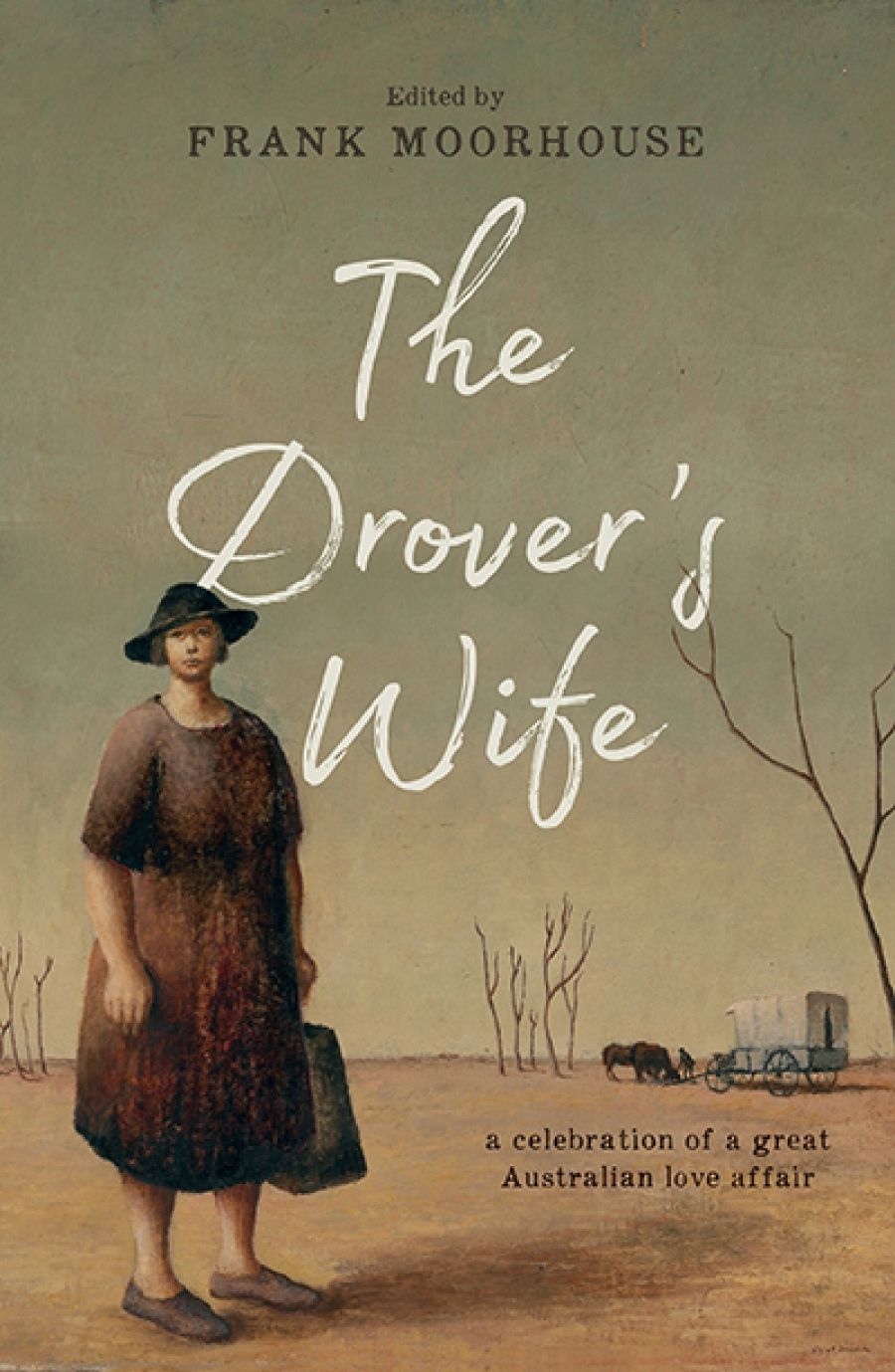

The real turning point for Lawson’s bush heroine came in 1945 when Russell Drysdale left a visual record of ‘The Drover’s Wife’ in one of his most recognisable canvases. As with many other attention-grabbing moments in Australian art and literature, Drysdale’s painting created a ‘shock of recognition’ as Australian viewers apprehended that, despite our many variegations, this depicted something of us as we do battle with our hard-scrabble piece of the globe, its deep history and complex present.

It is one of the unresolvable twists in Moorhouse’s account that Drysdale himself denied any influence of Lawson’s story upon his painting. Moorhouse obviously wishes that a direct line of influence could be provable, but it actually matters little. Drysdale ensured that Lawson’s story and the painting were joined by their shared title and arguably related subject matter. When Murray Bail published a story in 1975 explicitly linking the two, there could be no undoing of their entwined place in the national imagination.

As the stories Moorhouse gathers in this book go on to prove, playing the ‘Drover’s Wife game’ requires an author to link the figure of Drysdale’s ‘big woman’ (Who is she? What is in the case – or shopping bag – she holds at her side? Why does she carry such an air of implacable resignation? Is that the ‘drover’ in the background, and if so, what is he doing?) to key elements of Lawson’s story, in the process fleshing out the already substantial flesh of Drysdale’s version of the drover’s wife.

While Moorhouse has ‘edited’ this book, it is also substantially shaped by the eight chapters that he has written. In a sequence of three essays early in the book, Moorhouse describes his own shock of recognition when, over the course of his life, he has found traces of himself in the person of Henry Lawson. In particular, Moorhouse explores Lawson’s reported effeminacy, which he believes indicates a closeted homosexuality that was at the basis of Lawson’s close and lasting friendship with unsophisticated bushman Jim Gordon. (The relationship between Lawson and Gordon was the subject of Gregory Bryan’s Mates: The friendship that sustained Henry Lawson [2016].) Moorhouse argues that ‘Lawson belongs just as much with the LGBTQI movement as with any of the other individuals, and the nationalist and political movements, that have over the years claimed him, identified with him and used him’.

Frank Moorhouse (photograph by Kylie Melinda Smith)While the evidence Moorhouse presents for Lawson’s closeting is far from conclusive – and does not in itself throw substantial light on ‘The Drover’s Wife’ – it effectively destabilises understandings of Lawson and the bush ethos with which he is constantly associated. In other words, when we read Lawson’s ‘The Drover’s Wife’ and the subsequent fiction and art that ‘toy’ with that story, we should be conscious we are treading uncertain ground and need to be wary of the quicksand of assuming too much.

Frank Moorhouse (photograph by Kylie Melinda Smith)While the evidence Moorhouse presents for Lawson’s closeting is far from conclusive – and does not in itself throw substantial light on ‘The Drover’s Wife’ – it effectively destabilises understandings of Lawson and the bush ethos with which he is constantly associated. In other words, when we read Lawson’s ‘The Drover’s Wife’ and the subsequent fiction and art that ‘toy’ with that story, we should be conscious we are treading uncertain ground and need to be wary of the quicksand of assuming too much.

The individual pieces collected by Moorhouse include Lawson’s original story; an associated article from several years earlier by his mother Louisa; nearly a dozen pieces of short fiction (including Bail’s story and others by Barbara Jefferis, Mandy Sayer, David Ireland, and an outrageously amusing piece by James Roberts); a number of pictorial transformations of Drysdale’s ‘big woman’; and reference to versions in film and theatre; all of which run alongside Moorhouse’s own commentary on both ‘The Drover’s Wife’ and Henry Lawson. It makes for something of an unkempt collection, but it holds together well-enough to tell what Moorhouse (writing as Italian student Franco Casamaggiore) calls ‘a national culture joke’.

As enjoyable and occasionally thought-provoking as this collection is, the book seems to be without an obvious readership. Perhaps Lawson scholars; some Moorhouse followers, and cultural studies mavens. Which is a pity, because the stories we collectively tell are important, and the ones we compulsively retell become the most important of all. I, for one am pleased this book exists, and glad that I read it.

Comments powered by CComment