- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

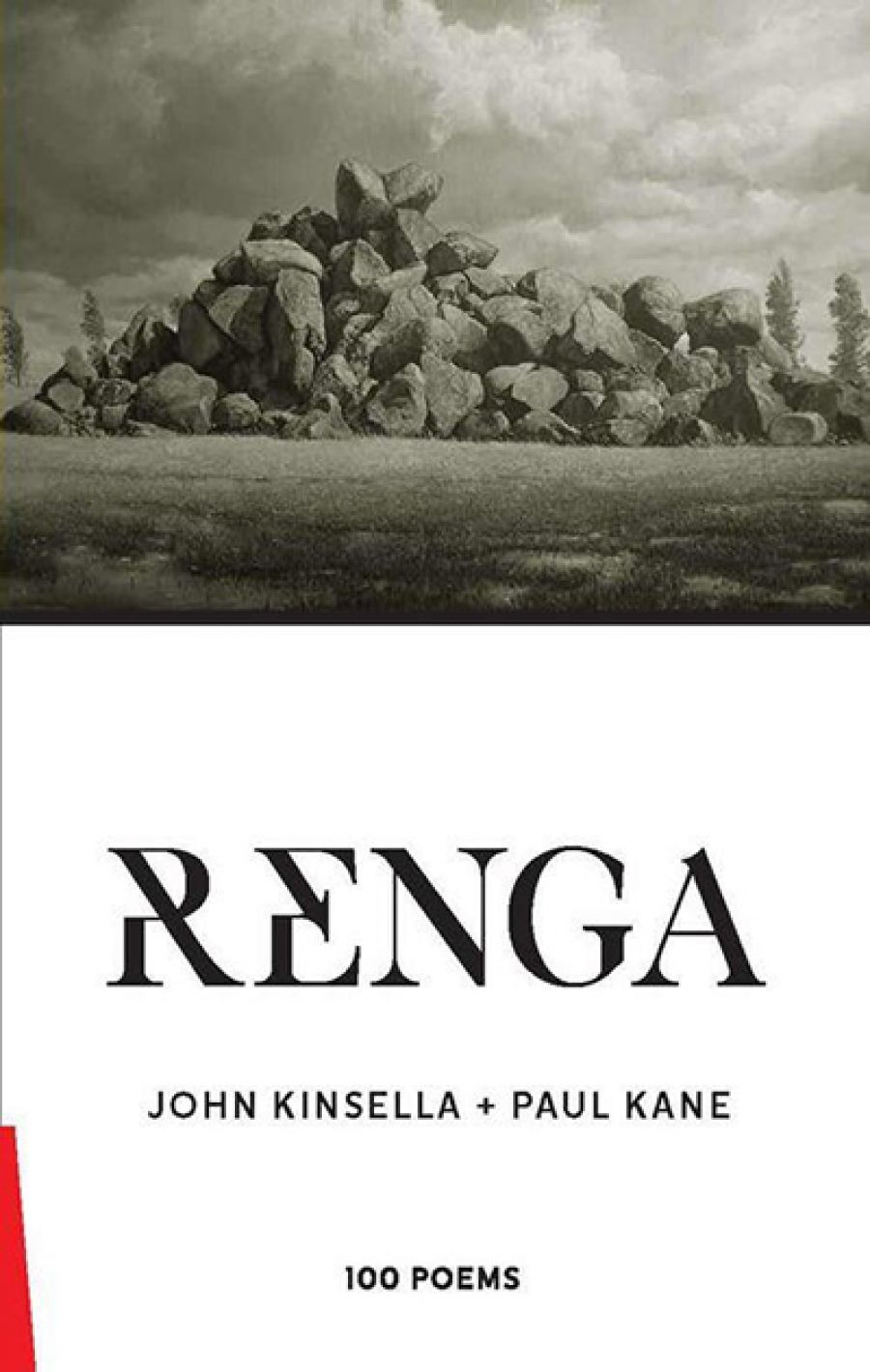

- Custom Article Title: David McCooey reviews 'Renga: 100 poems' by John Kinsella and Paul Kane

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Poets aren’t generally known for being great collaborators. Wordsworth and Coleridge’s 'Lyrical Ballads' (1798) is a rare example of a co-authored canonical work of poetry. 'Renga: 100 poems', by John Kinsella and Paul Kane, has some similarities to 'Lyrical Ballads'. Like those of its ...

- Book 1 Title: Renga

- Book 1 Subtitle: 100 poems

- Book 1 Biblio: GloriaSMH Press, $29.95 pb, 115 pp, 9780994527578

While Kane follows the Japanese stanza form’s syllabic structure of 5-7-5-7-7, Kinsella rejects that stricture for various free-verse configurations. These contrasting approaches might suggest a different ‘John and Paul’ creative partnership, though as with Lennon and McCartney the complementary differences are far more complex and productive than a simplistic ‘traditionalist-versus-iconoclast’ scheme would allow.

Renga is a powerful work of eco-poetics, meditating on modernity’s destructiveness and the protean experience of being in the world. While Kinsella is well-known for his political poems on the human degradation of nature, in Renga Kane is just as articulate in his search for a poetry that can accommodate, or deconstruct the opposition between, ‘the political’ and ‘the poetic’. In Renga 29, Kane decries mountaintop-removal coal mining: ‘It’s called MTR / in the Appalachian Range, a simple concept: / forget mining, just remove / the tops of mountains instead.’ Kane’s response to such practices, and the corrupt politics that allow them, is – in part – to back the potentialities of the everyday and poetic speech: ‘Start small, I say each morning, / a bird cry can crack a shell.’ But Kane also allows a more American post-Romantic position to emerge: self-reliance. In Renga 31, the poet (and ‘Graham, the electrician’) installs an inverter. In Renga 85, we see the poet chaining his self-built house to the earth, to stop it from being blown away.

As with Kane, Kinsella also focuses on both the extreme and the domestic. The poet in Kinsella’s poems is generally even more uneasy about the concept of home, presenting himself in Renga 42 as the ‘Perennial outsider, / trying to bloom / in drought’. More gothically, Renga 58 begins ‘Somebody much maligned died / and their soul passed partially / into me’. The gothic here is employed, as it is elsewhere in Kinsella’s poetry, as the obverse of the pastoral, that mode Kinsella has spent a career brilliantly revising and reworking. While there is nothing ‘ideal’, or even especially bucolic, in the pastoral landscapes that occupy Kinsella’s poetry, the natural world remains a source of solace (albeit a complex one), as seen in the memory, evoked in Renga 98, of river dolphins ‘dipping / and surfacing’. As this poem shows, even the act of citing a place name in a putatively post-colonial space can be unreliable. Freshwater Bay, it turns out, is not fresh water.

A dominant feature of Renga is its elegiac aspect. Mortality and impermanence are prevalent themes. Whether it is the death of Peter Porter (another transnational poet), bird populations (Renga 70 by Kinsella), or an unnamed partner (Kane’s deeply moving Renga 69), loss is universal in the pastoral context. In some of Kane’s poems, the self-elegiac note is also present. Renga 31 ends most powerfully in this register:

Interred in the ground,

I will not rise again, but

sink deeper within.

A nameless one, and faceless,

will sigh to be free of me.

The enigmatic (and faintly gothic) image of a self that is haunted by its own loss illustrates another element of Renga, one that is appropriate for such a dialogic work: an emphasis on duality, doubleness, and paradox. The collection repeatedly shows the continuity of apparently disjunct concepts: self and selflessness; the wild and the tame; subject and object. The evocation of doubleness in this dialogic enterprise is also seen in the creative use of repetition, as the two poets evoke and respond to earlier images, phrases, and themes. This echoic nature makes Renga very much a ‘collection’, rather than just a miscellany of discrete poems. It also marks the double nature of the book’s authors. Kane, an American, lives part of each year in Australia. Kinsella, an Australian, lives and has lived in America and the United Kingdom. As Kane writes in his Foreword, they recognised each other as ‘mirror images of each other’.

As the emphasis on dialogue and complementarity might suggest, Renga is not wholly freighted by the elegiac mood, or rather it shows how elegy and play are not mutually exclusive. Even mourning, these poems illustrate, must ultimately be creative. Linguistic playfulness is present in the work of both poets, as the wordplay in Renga 78 and Renga 79 shows.

Renga is the work of two master poets in compelling conversation. It illustrates both the richness and elegiac force of being in the moment. ‘Now is a word for / never again’, as Kane writes in Renga 13. It seems to me, as a long-time reader of both poets, that Renga has produced something new for each of them. Far from being an interesting footnote in the career of two transnational poets, Renga might be a central work in the oeuvres of its respective authors, offering (to use Kinsella’s words) intense ‘acts of navigation’.

Comments powered by CComment