- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

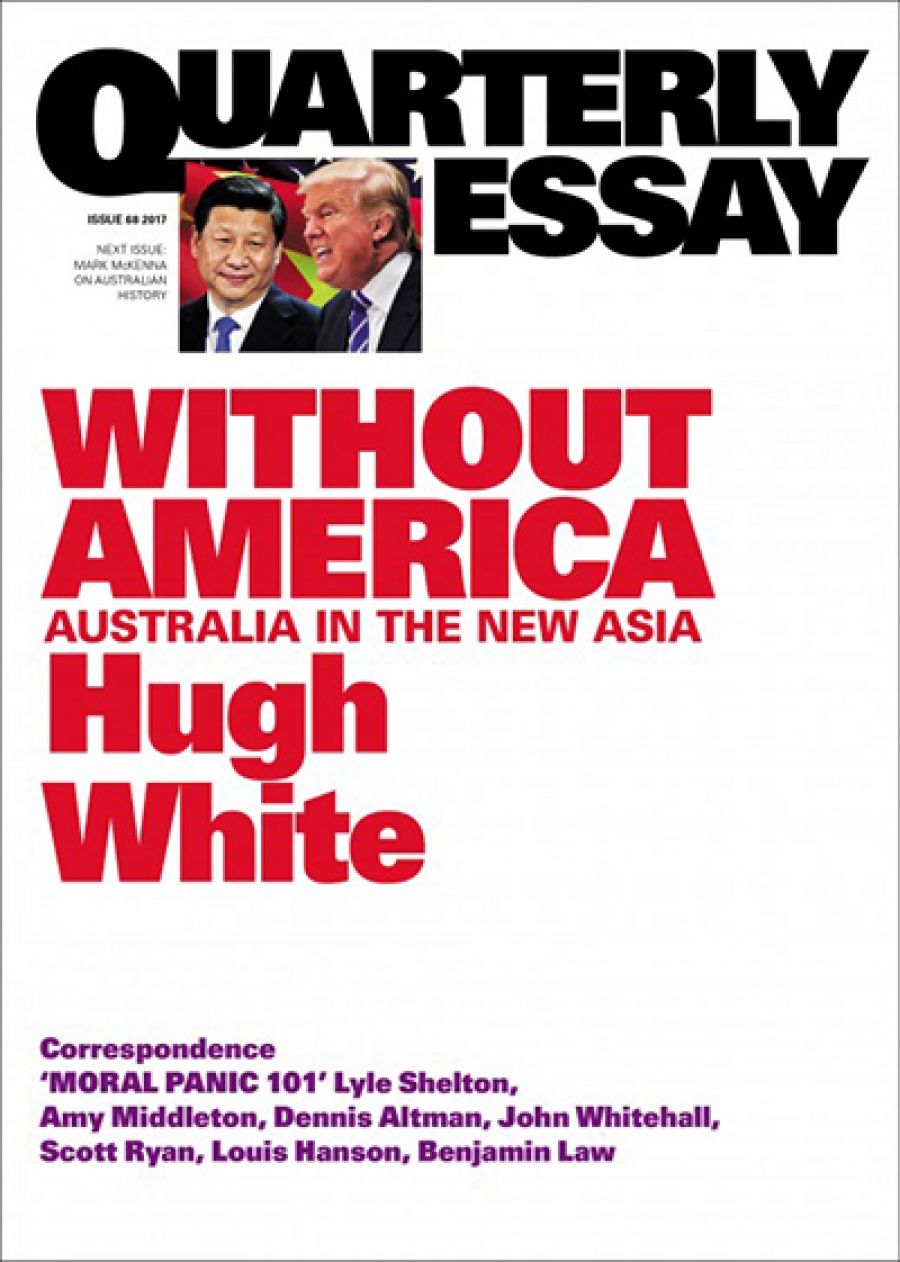

- Custom Article Title: David Brophy reviews 'Without America: Australia in the New Asia' (Quarterly Essay 68) by Hugh White

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For upward of a decade, Hugh White has been sounding a warning: that Australia’s long-standing policy of relying on the United States as guarantor of our security in Asia was approaching its use-by date. As a conspicuous relic of European colonial expansion, Australia has always viewed with trepidation the ...

- Book 1 Title: Without America

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia in the New Asia (Quarterly Essay 68)

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $22.99 pb, 108 pp

In the age of Donald Trump and Xi Jinping, the debate looks very different. Any window of opportunity that once existed for a power-sharing deal between China and the United States is now firmly shut, White believes. Chinese pre-eminence in Asia is inevitable, with events revealing an inexorable trend for China to weaken US influence, and to dissolve the bonds linking Washington and its allies. At some point, White warns, this delicate dance may devolve into a serious confrontation, a scenario he role plays for us in vivid terms. This will either end in a historically significant stand-down by the United States, or in a catastrophic war. White thinks the first outcome more likely, but warns that we should take the second very seriously.

White’s cool-headed analysis leads us into ‘the murky milieu of power politics’, where questions of values – those that supposedly unite us with the United States or separate us from the People’s Republic of China – don’t count for much. He is equally dismissive of the notion that the West is in Asia because our Asian allies want us there. Allies are required for those seeking to build hegemony from a distance, he points out; China has no need to contract such obligations in its own backyard.

White’s analysis is compelling, and this time around it hasn’t been so easy to will the conundrum away. In the wake of the Chinese Communist Party’s bombastic 19th National Congress, few could argue that China is about to reconcile itself to a ‘rules-based order’ imposed by the United States. One can always quibble about the time frame of China’s rise, but to do so is to admit his main point, that it is only a question of time. China might of course run into economic difficulties, or a political instability, but White sees no sign of this on the horizon. And in any case, banking on a collapse is hardly a viable strategy for a country so dependent on China’s continued economic growth. Indeed, Australia’s current policy settings indicate that Canberra concurs with White’s view of the US–China confrontation as a zero-sum game. Where our leaders evidently differ is in his conclusion that trying to keep China in its box is not a realistic option.

Left to right: Trần Đại Quang, Donald Trump, Xi Jinping, and Malcolm Turnbull (US Embassy Canberra, Wikimedia Commons)

Left to right: Trần Đại Quang, Donald Trump, Xi Jinping, and Malcolm Turnbull (US Embassy Canberra, Wikimedia Commons)

The idea of collaborating with the United States to contain China has long been a principle of Australia’s military posture. Turnbull and his ministry’s now frequent fulminations against Beijing only render that posture more explicit. Likewise, the most recent foreign policy White Paper signals a more serious effort to conceptualise a united front against China, shifting from talk of the Asia-Pacific – a space we share with China – to emphasise instead an Indo-Pacific perimeter. (Released in the same month as White’s Without America, this document might be dubbed ‘Without Asia’).

Meanwhile, journalists and pundits have busied themselves threading disparate half-truths and conspiracy theories involving Chinese influence in Australia into a narrative of the People’s Republic as an inherently, indeed uniquely, subversive actor in world affairs. An unfortunate corollary of this has been to treat calls (such as White’s) for discussion of alternatives to a pro-US foreign policy as apologias for totalitarianism.

We all stand to lose from this paranoid turn in Australian politics, but its immediate victims will be Chinese Australians, who must now assume that any intervention they make into Australian public life will be relentlessly scrutinised. For all the well-meaning efforts to rhetorically distinguish ‘Chinese Communist Party’ from ‘Chinese’ influence, the experience of earlier anti-communist witch-hunts in Australia should serve as a warning that it will be very hard to prevent this campaign from bleeding into anti-Chinese racism.

Hugh WhiteWhite’s essay thus provides us with an essential guide to thinking through a dangerous conjuncture in Australian politics. If he is correct, that the US commitment to Asia is waning for deep-seated reasons, then those hoping to preserve the status quo will have to do more than simply weather the Trump storm. To persuade Washington to stay in the game, Australia will have to show that it is willing and able to share the cost of propping up Western dominance in Asia. It will require, that is to say, a convincing display of Australian militarism. Throwing our own weight around as a means of stiffening US resolve is, of course, the same logic that led us into war in Vietnam. Yet for those drawn to the idea of a more independent foreign policy as an antidote to such militarism, White’s own prescriptions might be equally troubling. To defend itself, and uphold its interests in an Asia without America, White believes that Australia will require a wholesale restructure and expansion of its armed forces, entailing a significant increase in military spending.

Hugh WhiteWhite’s essay thus provides us with an essential guide to thinking through a dangerous conjuncture in Australian politics. If he is correct, that the US commitment to Asia is waning for deep-seated reasons, then those hoping to preserve the status quo will have to do more than simply weather the Trump storm. To persuade Washington to stay in the game, Australia will have to show that it is willing and able to share the cost of propping up Western dominance in Asia. It will require, that is to say, a convincing display of Australian militarism. Throwing our own weight around as a means of stiffening US resolve is, of course, the same logic that led us into war in Vietnam. Yet for those drawn to the idea of a more independent foreign policy as an antidote to such militarism, White’s own prescriptions might be equally troubling. To defend itself, and uphold its interests in an Asia without America, White believes that Australia will require a wholesale restructure and expansion of its armed forces, entailing a significant increase in military spending.

Hugh White’s essay leaves us with a bleak choice – between risking war with China to preserve US hegemony in the region, or fortifying ourselves so as to stand alone in a much less pliable Asia. For all the merits of his analysis, the chief conclusion we should draw from it is one that he himself avoids: we desperately need a more imaginative approach to the conduct of world affairs, and to Australia’s role in them.

Comments powered by CComment