- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Brian McFarlane reviews 'Anthony Powell: Dancing to the music of time' by Hilary Spurling

- Custom Highlight Text:

Readers of this review are warned that they are in the presence of an addict. Having read Anthony Powell’s monumental twelve-volume Dance to the Music of Time three times, I had been trying not to succumb to a fourth. Then along comes Hilary Spurling’s brilliant biography and will power has suffered total defeat ...

- Book 1 Title: Anthony Powell

- Book 1 Subtitle: Dancing to the music of time

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $55 hb, 525 pp, 9780241143834

There is, of course, more to Powell (1905–2000) than Dance, but that is above all what he will be remembered for. And that is what hovers over Spurling’s biography, with its extraordinary sense of interlocking lives, personal aspirations, successes, and disappointments, and its remarkable evocation of the changing times, politically, socially, and culturally. From Spurling’s account, Powell emerges as the source of the Nick Jenkins narrator-figure in Dance: that is, observer rather than observed, but a curiously palpable figure nevertheless.

In fact, the Jenkins character, from boyhood through to late middle age is one of the triumphs of the series. His voice is measured, with just enough attractive firmness to command the reader’s trust, and, in the wide-ranging diversity of his life’s choices, professional and personal, and of the other lives that intersect with his, he repeatedly echoes his creator’s dealings with the world. Spurling creates a sort of shadowy dance between the reality and the fictional representation that will make subsequent readings of Dance an even richer experience.

So what kind of man and life does this book put before us? As to Powell’s personal life, it is the wonderfully complementary marriage to Lady Violet Pakenham that gives it coherence. For more than sixty years, she became, in Spurling’s words, ‘a collaborator in the sense that, without her, the Dance to the Music of Time could hardly have taken the form it did’. As their son Tristram said of her memory, it was ‘the right arm, as it were, of my father’s imagination’. Another (unnamed) man became briefly ‘the love of her life’, probably during wartime years of long separation from Powell, but her ‘role as wife and mother exerted in the end a greater pull’. Powell’s discovery of the affair plunged him into the depression to which he was prone, but the strength of the marriage survived and each remained crucial to the other’s professional activities, Violet having also become a writer. He with his irascibly difficult father and she with her chilly mother seem to have been made for each other. They certainly needed each other, but don’t imagine this makes for soppy reading.

In spite of the overriding sense of Powell’s belonging to the upper-middle classes (and marrying a step up, becoming the brother-in-law of the seventh earl of Longford), he always had to earn enough to support his major writing ventures by taking on reviewing and editing jobs, especially in pre-war London. There were tiresome experiences with some publishing firms. In detailing these, Spurling vividly evokes what may well be a vanished world of people jostling for places in firms that settled for easy commercial success – or those with more high-minded aspirations. Powell was also a regular book reviewer for the once-popular journal Punch and later for the Daily Telegraph but his was essentially the mind of an author, especially of a novelist, with all other activities taking second place to that of the writer who needed the view from his study window obscured by a tree lest he be distracted.

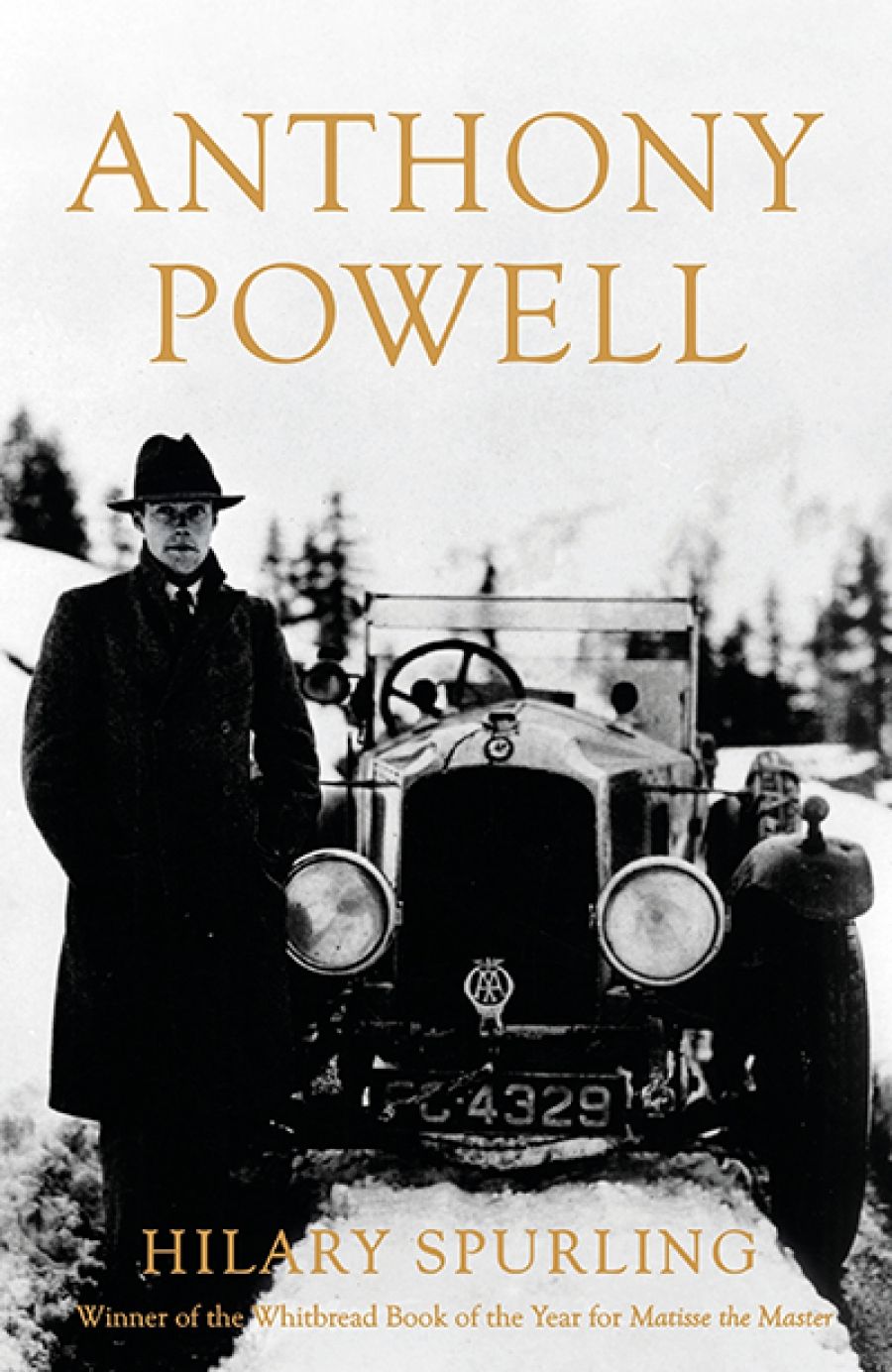

Anthony Powell (photograph by Dmitri Kasterine, Wikimedia Commons)

Anthony Powell (photograph by Dmitri Kasterine, Wikimedia Commons)

And yet, Spurling’s Powell isn’t wholly a solitary man. While sometimes overtaken by depression and exhaustion, he also took pleasure in enormous numbers of friends accumulated in his long life. Many such were fellow writers, such as Evelyn Waugh (Spurling’s dealings with him confirm other views of his waspish tongue and unreliable temper), George Orwell, Malcolm Muggeridge, Graham Greene, and (surely deserving reappraisal) Henry Green. The text is not just lavishly sprinkled with names of the famous: they get their vivifying share of time before the camera of Spurling’s eye for what makes people react to other people, for good or ill. Powell’s had been a lonely childhood, with a war-traumatised father, and the horrors of boarding school (he hated Eton) preceding the disappointment of Oxford: it is as though this unprepossessing start to life had inclined him to value the gifts of family and friendship which so characterised his life as they would do his alter ego Nick Jenkins.

Again and again one is struck by how Powell transformed real-life acquaintances into memorable fictional figures. For example, battling husband and wife the warring Cyril and Barbara Connolly, wittily sketched by Spurling, are the prototypes of Dance’s pugilistic Macklinticks. Most memorable of all, though, is the reincarnation of Lt-Col. Capel-Dunn, ‘short, stout, graceless, totally lacking in humour and superlatively good at his job’ as Powell’s Widmerpool, as riveting a study of an ego utterly devoid of self-knowledge as twentieth-century fiction has given us.

Not only is Spurling’s research exemplary, but she also knew Powell the man. She seems to have grasped his ‘peripatetic existence’ and the times in which he lived it with effortless dexterity.

Comments powered by CComment