- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

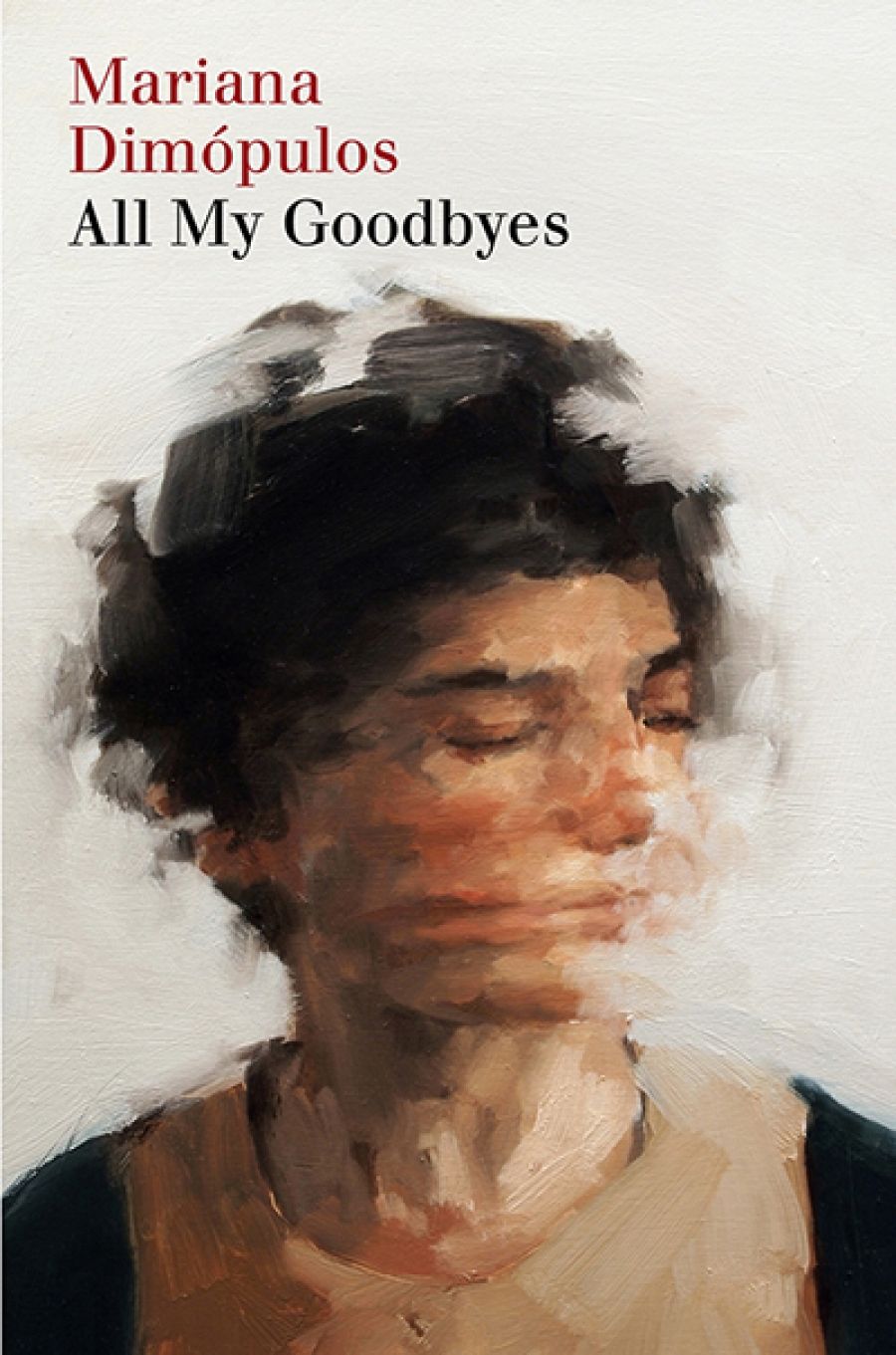

- Custom Article Title: Lilit Thwaites reviews 'All My Goodbyes' by Mariana Dimópulos, translated by Alice Whitmore

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Given that the unnamed narrator–protagonist of Mariana Dimópulos’s All My Goodbyes (Cada despedida) has difficulty putting together and understanding her own fractured, nomadic life, it is perhaps not surprising that we readers have to call on all of our faculties to reconstruct her narrative – but it is well worth the effort ...

- Book 1 Title: All My Goodbyes

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24.95 pb, 160 pp, 9781925336412

Interestingly, Dimópulos, who is from Argentina, is herself a translator (from German and English into Spanish), and frequently immerses herself in what she calls ‘games of linguistic chess’. Language and words are a feature of her life and of her writing, along with explorations of location, displacement, movement, and riddles.

She is the author of three published works of fiction – Anís (2008), this book, Cada despedida (2010), and Pendiente (2017) – as well as short stories and non-fiction, including a critical study of the work of the German philosopher, translator, and cultural critic Walter Benjamin. All My Goodbyes is her first work to be translated into English, and launches Giramondo’s new series ‘Southern Latitudes’, which aims to bring together writers from the southern hemisphere and allow their work to resonate with Australian readers.

The protagonist of this novella – a genre that features prominently in the work of many contemporary writers from Latin America – is a young woman from Buenos Aires with a fractured life and an acute case of ‘suitcase syndrome’. She informs us early on that ‘at twenty-three I was already ancient’, and ‘rather than fall into introspection and rummage around in my own muddy depths I preferred to pack my bags, to inaugurate something, the next thing’. She is – or was – a biologist and chemist, and an inveterate liar, perhaps in part because, after her mother died when she was four or five, she was raised by her father, a physicist, who ‘simply enjoyed tainting with doubt [scepticism] everything I was beginning to believe ... naïve with his wisdom, a well-intentioned butcher of innocence’. Is this in part why she feels – and frequently tells us – that her heart, ‘neither fair nor kind’, is ‘cut from a bad cloth’? Why she ‘had no love for myself. I was good for nothing’? Why, after ten years in the Old (Northern) World where she did connect emotionally with three or four people, albeit briefly, she finally returned to Buenos Aires and then quickly fled from there to Patagonia, and ‘never saw any of [those people] again. I never spoke to any of them again ... I put an end to them all, I didn’t leave a trace, didn’t feel a trace of remorse. These are all my crimes: all my goodbyes’?

Mariana DimópulosLike the narrator of All My Goodbyes, with whom she shares the ‘suitcase syndrome’ or travel bug, Dimópulos decided to leave Buenos Aires in her early twenties. But unlike her character, who spends ten years constantly on the move, Dimópolos knew exactly where and why she was going – to read the works of the philosophers of the Frankfurt School. This entailed travelling to Germany and, among many other things, discovering and learning the German language. In the process, she realised that coming across someone who speaks your own language can be a plus when you are living in the daily swirl of a place where you don’t know the language and cannot interact with the locals. It can open up a space of sorts, a quietness, perhaps even a momentary sense of ‘arrival’.

Mariana DimópulosLike the narrator of All My Goodbyes, with whom she shares the ‘suitcase syndrome’ or travel bug, Dimópulos decided to leave Buenos Aires in her early twenties. But unlike her character, who spends ten years constantly on the move, Dimópolos knew exactly where and why she was going – to read the works of the philosophers of the Frankfurt School. This entailed travelling to Germany and, among many other things, discovering and learning the German language. In the process, she realised that coming across someone who speaks your own language can be a plus when you are living in the daily swirl of a place where you don’t know the language and cannot interact with the locals. It can open up a space of sorts, a quietness, perhaps even a momentary sense of ‘arrival’.

It is only when Dimópulos’s nomadic protagonist arrives at the Del Monte farm near the isolated town of El Bolsón in Patagonia, sees the orchards and berry fields, is hired as a summer worker and eventually allowed to stay on and live in one of the three houses owned by the equally taciturn Marco and his wealthy, ‘sweet and malicious’ old mother, Madame Cupin, that she realises that ‘love exists and the place exists’. She has become ‘a magnificent animal: soft, compact, whole’. For the first time in her life, she can ‘sit and recline without a shred of [her father’s] scepticism, trusting completely in the resilience of chairs and beds’. Does it last? The horrendous crime described in the opening pages of All My Goodbyes suggests otherwise, but it is left to the readers to complete the puzzle.

Comments powered by CComment