- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

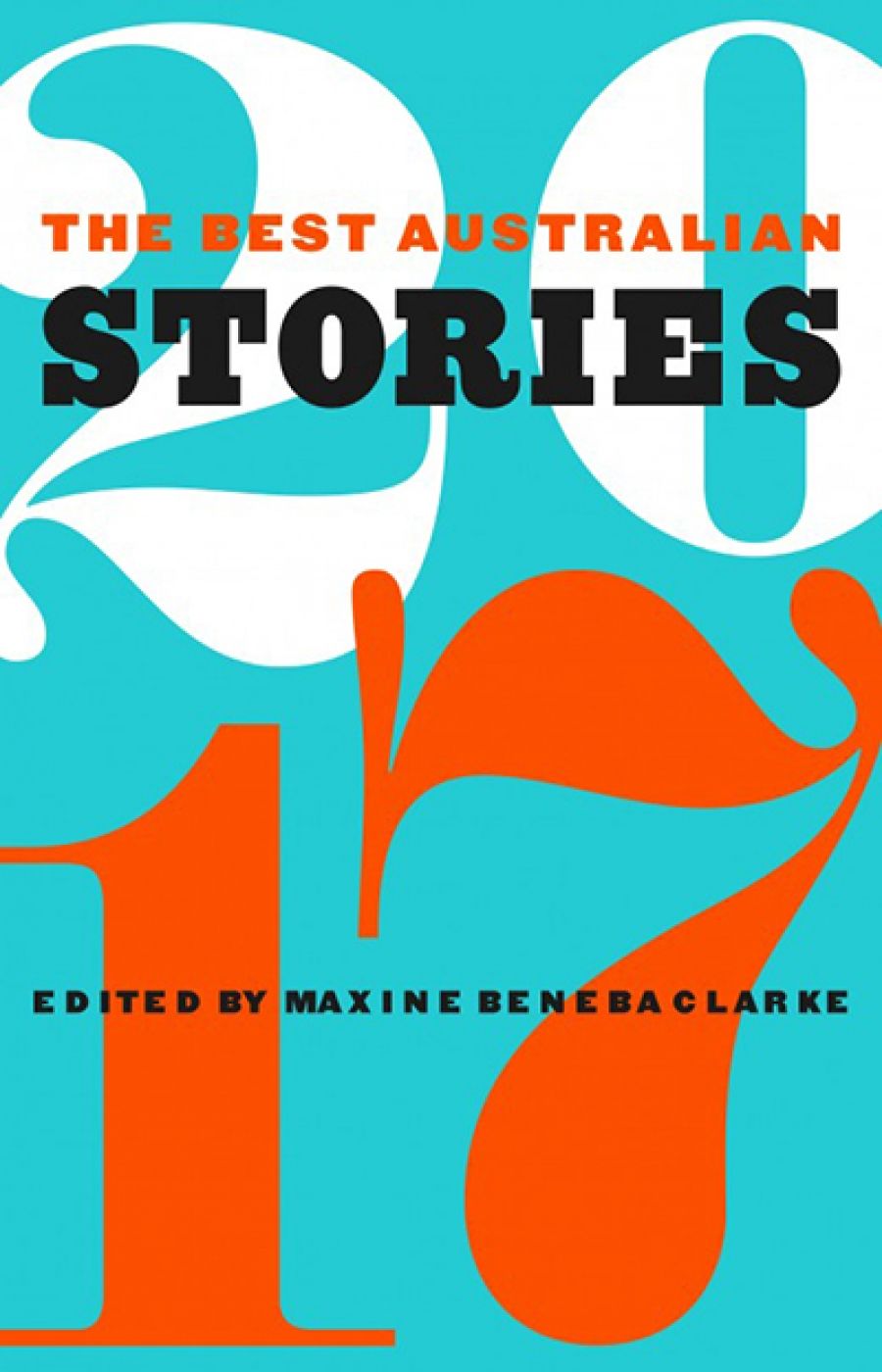

- Custom Article Title: Rachel Robertson reviews 'The Best Australian Stories 2017' edited by Maxine Beneba Clarke

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her Introduction to The Best Australian Stories 2017, Maxine Beneba Clarke describes how the best short fiction leaves readers with ‘a haunting: a deep shifting of self, precipitated by impossibly few words’. Many of the stories here achieve this, inserting an image or idea into the reader’s mind and leaving it there to worry ...

- Book 1 Title: The Best Australian Stories 2017

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.99 pb, 188 pp, 9781863959612

In ‘Miracles’ by Jennifer Mills, a boy comes home from school one day radically altered. His mother mourns her old son and his childhood. Soon other children in the town change and stories begin to circulate about the cause of this. It might be one of these stories, in the end, that does as much harm as the changes themselves. ‘Dreamers’ by Melissa Lucashenko also features a mother, a lost child, and a mystery. In this case, the grief is shared: ‘And the terrible thing which would have driven any other three people far apart instead bound them together.’ This story, like Tony Birch’s ‘Sissy’, is shadowed by the lost and stolen children of Aboriginal Australians. When Sissy is offered a holiday with a wealthy white family, she is initially thrilled, but her mother is less keen. Will it be safe and how can they trust the charity involved?

A child taken by ideology features in ‘Help Me Harden My Heart’ by Dominic Amerena, which opens with a woman scrubbing ‘the word SCUM’ off her front door. Her neighbours are both friends and foes in this tragic tale. In ‘Glisk’ by Josephine Rowe, two brothers struggle with the legacy of a careless act and the memory of children harmed. A young boy accidentally overhears something in a girl’s room in John Kinsella’s ‘The Telephone’, while in Raelee Chapman’s ‘A United Front’ a young man wants to protect a newborn baby.

Some of these stories are set in the past, some in a potential future, and a few in a parallel, more surreal, world. The hovering spectre of the lost child, however, made me think that underlying these stories is a recognition that we are already living in an Australia that will soon be past, that we have already taken the decisions that will destroy our planet. If the image of the child is a representation of the future, perhaps such stories are performing our work of grieving for our own children’s blemished futures and the lost children of the future.

‘The Boat’ by Joshua Mostafa imagines a future for white middle-class Australians that is a reality for many people around the world – the need to flee their homeland in order to survive. Elizabeth Flux’s ‘One’s Company’ shows an immigrant boy splitting into two halves, with the marvellous beginning: ‘As they stepped off the plane, Zhen’s mother turned to hold his hand and was met with two different versions of her son. She tsk’d impatiently. There were bags to collect and paperwork to fill out – she didn’t have time for magical realism.’ Julie Koh’s ‘The Wall’ conjures a wall across Australia to keep the Chinese out, which happens to run right through the middle of the protagonist’s bedroom. ‘“My husband will have something to say about this,” I tell them, but he is nowhere to be found.’ We learn later what the husband is doing.

Maxine Beneba Clarke (photograph by Nicholas Walton Healey)

Maxine Beneba Clarke (photograph by Nicholas Walton Healey)

There is humour and satire in this collection and both realist and fantastical modes. The works – diverse in tone, style, and voice – come from established and emerging writers. The stories come from a range of publications (with two of the twenty-one stories not previously published), showcasing the valuable work that Australia’s literary magazines perform. Are they the best short fiction published in 2017? This I can’t tell, though Clarke notes she chose from ‘hundreds upon hundreds’ of stories. These are all excellent works which more than repay time spent reading them. Many of them stayed with me for days. I keep wondering what choice I would make were I the woman driving the ute in Verity Borthwick’s ‘Barren Ground’. I continue to be unsettled by the girls in Beejay Silcox’s ‘Slut Trouble’ and the idea of twinning in Mirandi Riwoe’s ‘Growth’. I wish I could write in the voice of a child as Madeline Bailey does in ‘The Encyclopedia of Wild Things’, where, ‘All of us built the fox but it went wild. It kept soaking up stories, so we couldn’t stop it growing and we had to make a plan to protect parents.’ Yes, indeed, stories can be dangerous, as this and other works in the collection make clear. Stories we tell ourselves, stories others tell us, and our political stories – all can be dangerous. But they are also nurturing and enriching, even life-saving. Even as we move towards death, stories can hold us, as Ellen van Neerven shows in ‘Sis Better’, which ends with an arrival and the words, ‘Today I’m here.’

Comments powered by CComment