- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

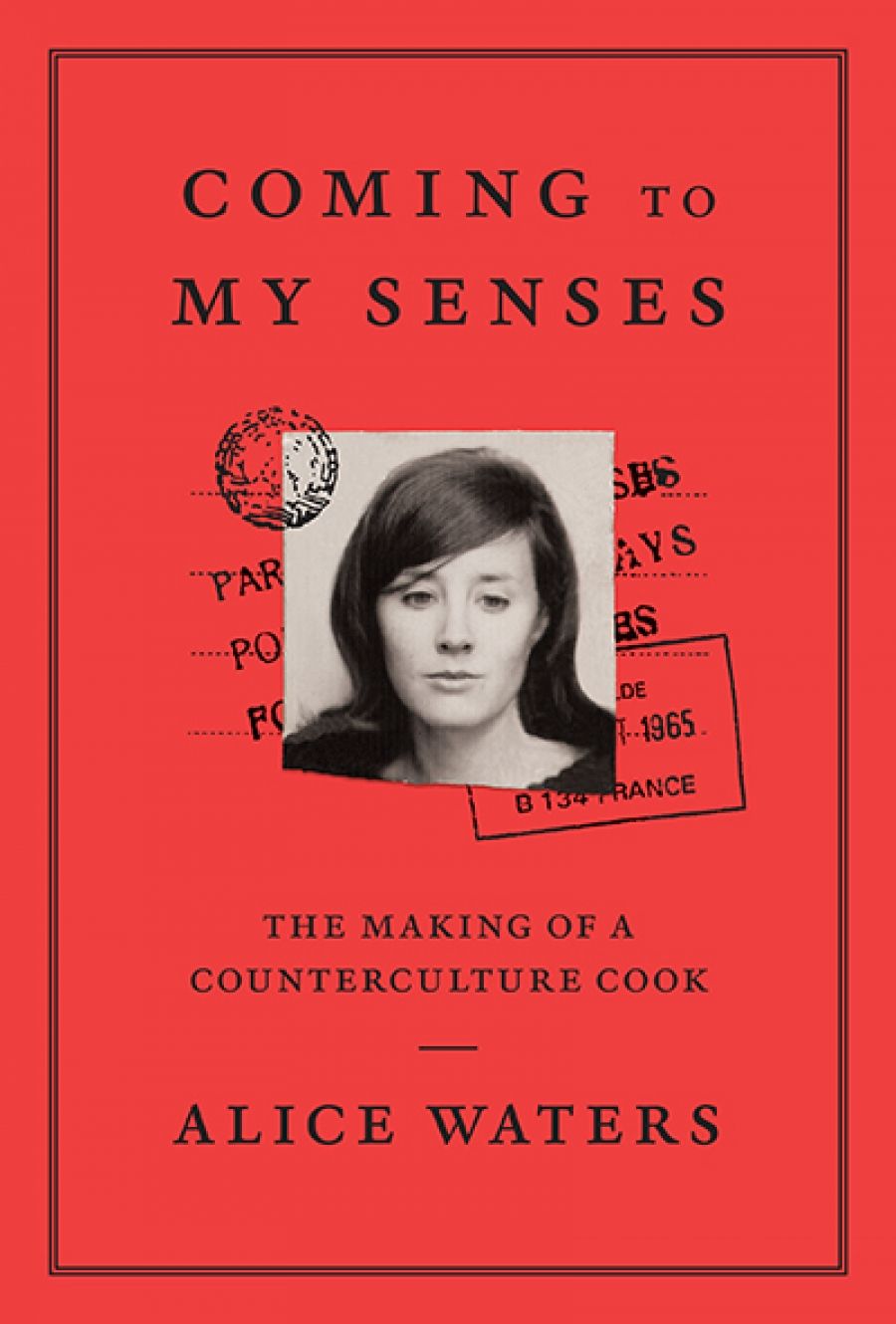

- Custom Article Title: Mimi Biggadike reviews 'Coming to my Senses: The making of a counterculture cook' by Alice Waters

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is a colourful and turbulent life Alice Waters leads. Thankfully, it is turbulent in the fruitful sense, a process of regeneration and creation so nimbly edited into her autobiography ...

- Book 1 Title: Coming to my Senses

- Book 1 Subtitle: The making of a counterculture cook

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $39.99 hb, 320 pp, 9781743793862

For the unacquainted, Chez Panisse, founded in 1971, is an American institution, in a particularly unAmerican fashion. First, it is a French restaurant. Second, it is known for its antithetical stance to US culture: absolutely no doughnuts are permitted. Fast food is referenced with debasing fervour, held partly culpable (and at the very least emblematic) by Waters for the multiple failings of modern America. She speaks of disconnection in its many guises: from our society, our stomachs, and ourselves. Although politically charged, it is not a call for action. There is, indeed, a placid acceptance reminiscent of William Cobbett’s cry, ‘I defy you to agitate any fellow with a full stomach.’ Although separated by nearly 300 years, this tacit acknowledgment of the fundamentally comfortable classes remains astute. Food is no longer a necessity, it is a distinguisher: both in terms of wealth and political inclination. This is true to such an extent that when Waters urges us to remember ‘Food is alive’, it comes as a bit of a shock.

With a life guided by such an aesthetic sensibility, it seems fitting that the restaurant was named after a character from a Marcel Pagnol film: Panisse the French provincial sailmaker who saves the day with his chivalry. Food and film are gracefully matched as the two main loves of her life, mediums through which to find fulfilment. Nourishment is a word used here throughout. Larger themes, those of love and politics, the perfect lettuce leaf, are deftly navigated through pithily titled chapters. ‘Queen of the Garden’, for example, holds up a specific moment for examination within a wider context, a wider lens through which to view a life.

Ending with the opening of the restaurant, Waters’s autobiography simmers with ambition, flavour, and finely realised nuance – not unexpected from someone who is widely hailed as single-handedly propagating the Slow Food movement in America. Part of the ambition is its use of multiple mediums to explore thoughts and themes. Recipes, letters, photos, hand-calligraphed menus, and other such materials are interjected throughout. They uphold the structure and solidify the various pertinent vignettes that Waters conjures with ease in her happy prose.

For such considered exactitude in all years previous to the opening, the event itself seems ingloriously crammed into the final chapter. The restaurant floats conceptually throughout; it is the end-goal, the unifying semantic. It is unnerving, then, to watch it materialise so messily. The writing here seems mimical of this chaos. A rushed and gregarious prose suited to a chaotic night of late meals and the soon-regretted decision to have swing doors into the kitchen. Needless to say, a lot of plates were smashed.

Alice Waters (photograph by David Sifry, Wikimedia Commons)

Alice Waters (photograph by David Sifry, Wikimedia Commons)

It would be unfortunate to omit Waters’ two collaborators, Christina Mueller and Bob Carrau, without whom, as she herself states, there would be a nonsensical rift in her ‘efforts to recapture the past’. As with everything in her life, there is a strong emphasis on community in the book, a strength that shines forth even without her heartfelt thanks in the lengthy acknowledgments. The decision to defy chronology and include direct interjection, often in the present tense, into the main body of text, and to distinguish it with italics, is inspired. It is a collaboration through and through: from the people in Waters’ life gifting ideas and encouragement in the past, to the person editing and placing an expertly timed comma during construction.

The aforementioned ambition of her book has an easy pragmatism, synonymous with her philosophy. She is erudite, ambitious, and kamikaze. And so is the craft of her autobiography. The steely determination necessary to achieve this is evident in even the young Alice; the book is laced with wonderful moments of rebellion, from incurring her mother’s wrath when jumping around at four years old when supposed to be in bed with scarlet fever, to biting a child (himself a prolific biter) at a Montessori school. She was his teacher at the time.

Coming to My Senses is warm and fascinating, without being sentimental. Waters’ ability to couple thoughts and reminiscences into unison is echoed in her ability to match flavours. Everything is synchronised and harmonious, and weird as it may sound, it reads like the menu of a life – one filled with both wonder and wonderment. Alice Waters is a woman who looks at life as though it were a (doubtless French) film, and one who thinks through food.

Comments powered by CComment