- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

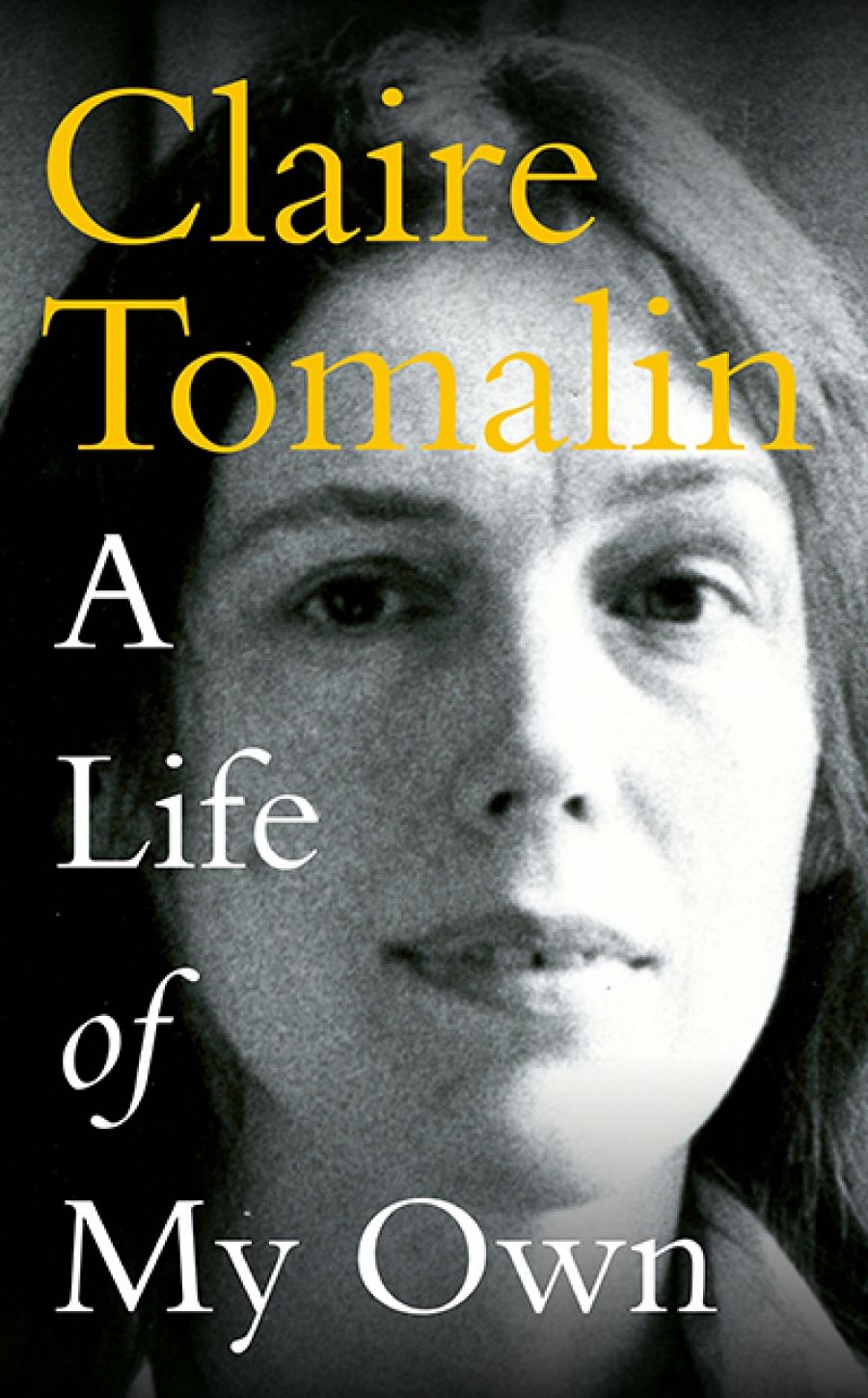

- Custom Article Title: Brenda Niall reviews 'A Life of My Own' by Claire Tomalin

- Custom Highlight Text:

When a biographer tells her own story, the rules change. Because the subject is the self, the problem is not so much a search for the unknown, but what to tell about the known and how to tell it. One of Britain’s finest biographers, Claire Tomalin, has spoken of her pleasure in ‘investigating’ other people’s lives. What happens ...

- Book 1 Title: A Life of My Own

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $55 hb, 352 pp, 9780241239957

Tomalin came down from Cambridge with a First in English to find that the best jobs were taken by men, but she made the most of the crumbs as a reader for a publisher. One of her interviewers at Heinemann was designated to rate her for looks. She learned later that he had given her only seven out of ten. At twenty-one, she married fellow graduate Nick Tomalin, who was ‘funny, quick, affectionate, generous, original – and hard to resist’.

Nick and Claire had five children. The first, a son, died a few weeks after birth and the fifth, Tom, was born with the severe handicap of spina bifida. ‘Who will love him?’, she asked, and from the heart she replied: ‘I will. And I will see that he has the best possible life.’ She wrote with Tom’s carrycot beside her. Like Jane Austen, with no space of her own, she tidied her work out of sight when guests came.

Tomalin was forty when she wrote her first book, a life of Mary Wollstonecraft, in which she had an almost unexplored field. With later biographies, on Shelley, Austen, Pepys, Hardy, and Dickens, she entered some hotly contested sites. The Invisible Woman, her biography of Dickens’s mistress, the young actress Ellen Ternan, was a tour de force of detection. Ternan’s relationship with Dickens was so carefully hidden that only an impressive blend of persistence, inspired guesswork, and the close interrogation of public records could have brought it to light.

Some admirers of Dickens attacked the Ternan book, on the grounds that it damaged a reputation without certain knowledge. But Tomalin has never been afraid to speculate, while making it clear just what is known and what is guesswork based on human probability.

Believing that biography is best written by those old enough to have had experience of life, Tomalin doesn’t regret her late start. Nor does she see her life as determined by her own private tragedies. She looks back without rancour towards those who injured her, and without bitterness about the blows of fate that she has endured. The passage of time, her second, happy marriage, her pleasure in her work, and the recognition it has brought her combine to give this memoir a remarkable serenity. Life, she says, is seamless; the bad and the good co-exist. When Nick Tomalin, on a journalist’s assignment in Israel in 1973, was killed by a Syrian missile, she didn’t dwell on the betrayals of her marriage. She felt ‘as though the sun had been eclipsed’. She also felt pride in being strong enough to stand alone.

Tomalin flourished as literary editor of the New Statesman and later of the Sunday Times. She was confident in her judgements of books (Clive James called her ‘Clara Tomahawk’) and fearless in denouncing ‘ruthless and bullying management’ during Rupert Murdoch’s war with the print unions. At fifty-three, she became a full-time writer.

Claire Tomalin (Wikimedia Commons)Writing biography, Tomalin felt ‘intensely happy’. She had found her vocation – ‘late in life but it changed everything for me’. She also found personal fulfilment: her long, close friendship with writer Michael Frayn turned to ‘middle-aged love which proved stronger than anything [she] had known before’. A quietly supportive presence, Frayn doesn’t come to life for the reader as does the irresistible betrayer Nick Tomalin. That’s the privilege of memoir. In a biography, the relationship with Frayn would have been explored, and the name of another lover would not have been withheld.

Claire Tomalin (Wikimedia Commons)Writing biography, Tomalin felt ‘intensely happy’. She had found her vocation – ‘late in life but it changed everything for me’. She also found personal fulfilment: her long, close friendship with writer Michael Frayn turned to ‘middle-aged love which proved stronger than anything [she] had known before’. A quietly supportive presence, Frayn doesn’t come to life for the reader as does the irresistible betrayer Nick Tomalin. That’s the privilege of memoir. In a biography, the relationship with Frayn would have been explored, and the name of another lover would not have been withheld.

Tomalin writes poignantly about Susanna, her brilliant second daughter who killed herself at the age of twenty-two. ‘I should have protected her, and I failed.’ Her two living daughters are mentioned with loving pride but, like Frayn, they are allowed their privacy.

Tomalin is more than a literary detective; her human sympathy and her gift for asking the unexpected question make her biographies exceptional. Her 1997 life of Jane Austen was published at the same time as one by David Nokes. What could either of them contribute to the understanding of the few known facts of Austen’s life? Quite a lot, as it turned out: on certain episodes in Austen’s life, they disagreed quite markedly. Tomalin, I thought, had the edge: she wrote simply, with none of Nokes’s embarrassingly arch interior monologues; and psychologically she was more astute. One example: there is no way of knowing the effect on the infant Jane Austen of being sent away to a village wet-nurse after three months of breast-feeding by her mother. But, as Tomalin wrote, when she drew on modern theories of maternal deprivation, ‘you have to wonder’. Her own experience as a working mother who faced difficult choices and experienced great joy as well as tragedy made her alert to a family pattern that had never been explored.

Now in her mid-eighties, Tomalin has written the memoir which might be expected to end her career. But she is keeping an open mind; she may well write another book. As a biographer who is much of an age with Tomalin, I find that heartening.

Comments powered by CComment