- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

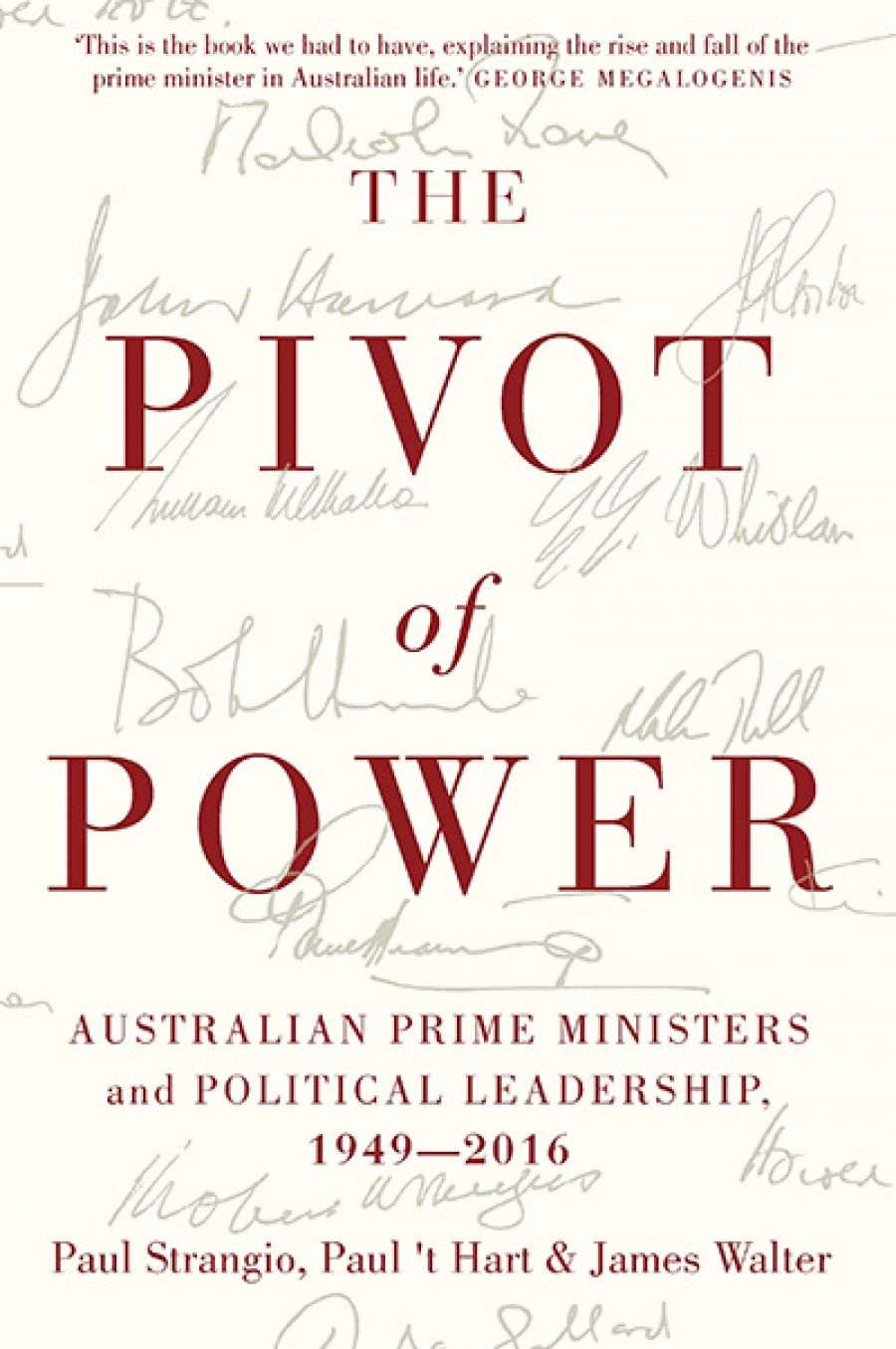

- Custom Article Title: Frank Bongiorno reviews 'The Pivot of Power: Australian prime ministers and political leadership 1949–2016' by Paul Strangio, Paul ‘t Hart, and James Walter

- Custom Highlight Text:

Has the Australian prime minister’s job become impossible? The authors of The Pivot of Power: Australian prime ministers and political leadership 1949–2016 ask this question at the very end of their book. They conclude on an almost utopian note, one rather out of keeping with the otherwise judicious tone maintained over ...

- Book 1 Title: The Pivot of Power

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian prime ministers and political leadership 1949–2016

- Book 1 Biblio: The Miegunyah Press, $49.99 hb, 376 pp, 9780522868746

We expect a great deal of our prime ministers – perhaps more than ever – but we also subject them to a level of scrutiny that would have struck Robert Menzies, whose long postwar prime ministership (1949–66) opens this book, as downright impertinent. If asked by a journalist for passing comment, Menzies would simply advise the enquirer to listen in parliament. But by the time we get to John Howard, there is a media unit with eight staff, a veritable spin factory. Rudd’s prime ministership notoriously degenerated into a quest for the next ‘announceable’.

The authors suggest that Menzies has a great deal to answer for, mainly because he was so good at his job. No other political figure managed to fill the prime ministership as he did. He weighed like a nightmare on the brains of his successors because he became the benchmark for prime ministerial performance: a masterful political communicator, superb tactician, astute judge of civil service talent, and a creative thinker about party philosophy. He dominated ministerial colleagues, party, parliament, and media, and he presided over a politically propitious combination of Cold War and long boom. No wonder he won seven elections on the trot. And he also achieved a standing as a respected international statesman to which his successors could only aspire.

Menzies made his mistakes. There was his support of Britain in the Suez crisis, and he became out of touch with the way Australia was changing in the 1960s. But it was a long way downhill from him to his three Liberal predecessors, Harold Holt, John Gorton, and William McMahon. Holt, Menzies’ hand-picked successor, was an amiable man who ‘misjudged his strength’, the authors suggest, both in the Portsea surf and in ‘the highest office in the land’. Gorton was clever enough to understand that he needed to break the Menzies mould entirely by forging a different image of ‘strong leadership’, but his personal idiosyncrasies and erratic political style proved too much for a party still living in Menzies’ giant shadow. McMahon, in formal terms, was well prepared for the prime ministership with his years of ministerial experience and his training in economics, but proved a failure on the job.

The paradox of ‘the burden of succession’, however, was that the very inability of Menzies’ successors even to approach the benchmark be had set meant that they sought ways to augment the office. Gorton, for instance, famously selected the formidable Lenox Hewitt as secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department in the expectation that he would be the prime minister’s ‘“go to” man’. The changes in government machinery of this era were modest by later standards, but they laid the groundwork for prime ministerial government.

Robert MenziesWhitlam’s prime ministership is a watershed in the story of the office of prime minister. Not only was he the first prime minister of the post-Menzies era who looked as though he might be capable of emulating the Liberal prime minister’s gravitas, but he made changes to institutional arrangements that planted the seeds of the future growth of prime ministerial resources and power. As opposition leader, Whitlam had built up a rich network of policy expertise that he wanted to be able to continue to exploit in office. The development of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) as a source of both policy and political advice, along with the reconfiguration of the Prime Minister’s Department (PMD) as a policy powerhouse, owed a great deal to the Whitlam era. The trend was magnified under Malcolm Fraser: the role of the prime minister as chief economic manager now emerged.

Robert MenziesWhitlam’s prime ministership is a watershed in the story of the office of prime minister. Not only was he the first prime minister of the post-Menzies era who looked as though he might be capable of emulating the Liberal prime minister’s gravitas, but he made changes to institutional arrangements that planted the seeds of the future growth of prime ministerial resources and power. As opposition leader, Whitlam had built up a rich network of policy expertise that he wanted to be able to continue to exploit in office. The development of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) as a source of both policy and political advice, along with the reconfiguration of the Prime Minister’s Department (PMD) as a policy powerhouse, owed a great deal to the Whitlam era. The trend was magnified under Malcolm Fraser: the role of the prime minister as chief economic manager now emerged.

While Strangio, ‘t Hart, and Walter do produce, among other things, something like a de facto history of the PMO and the PMD, their approach is also biographical. Each man brought to the job a background and personality that would shape their aspirations and performance. Whitlam was the son of a senior public servant who had spent part of his formative years in Canberra, and this animated his faith in the ability of a central government to act as the instrument of his goals. Fraser was an Oxford-educated Victorian grazier whose solitary upbringing had bred self-reliance along with a sense of life as a battle, and of politics as a contest of wills. Both found their time in office haunted by the economic problems that came with the end of the long boom.

Bob Hawke’s prime ministership has come to be seen as a gold standard, but the times were favourable for creative leadership. By the early 1980s the old protectionist state could no longer sustain economic prosperity and living standards. Here was an opportunity for ambitious reformers, but the authors argue that the success of the government owed much to Hawke’s model of ‘distributed leadership’, which empowered a talented group of ministers, most importantly among them the young Paul Keating. The authors accept the orthodoxy that this partnership was central to the government’s success. While Hawke had a notoriously large ego, he also had the wisdom to allow his ministers to get on with their jobs and was an effective cabinet chair. Keating, when he came to the prime ministership in 1991, was careful to avoid recriminations from his battle with Hawke, but less able in the chairing role, less inclined to delegate, and occasionally in the habit of cutting the cabinet out of important issues entirely. But Keating’s aspirations for the office were Whitlamite in their ambition – he would redefine Australia’s identity, reshape its place in the world.

John Howard was ideally suited to exploiting the hubris that lurked at the heart of this idea, and the authors recognise just how successfully he moulded the prime ministership to his times and his purposes. He cultivated the image of the ordinary man, yet he was ideologically creative and made excellent use of the media, especially talkback radio. Howard was also a fine manager of people: he never took party support for granted, even sometimes joining backbenchers in the parliamentary dining room, and he surrounded himself with a highly effective policy and political machine. But like Keating he eventually grew out of touch, the quality of his decision-making declining in his final years.

John Howard

John Howard

This issue of the party is critically important: for ordinary voters, the leader stands in for a party otherwise often invisible. And yet what the party giveth, the party taketh away, a reality learned too well by a succession of discarded prime ministers in the leadership churn of recent times. The problem of needing to serve two demanding masters – party and public – has been especially pointed for Malcolm Turnbull. It is a tightrope that would confound the cleverest performer, especially in the age of social media and the 24/7 news cycle.

The Pivot of Power is the sequel to Settling the Office: The Australian prime ministership from Federation to Reconstruction, published in 2016. Considered together, the two volumes are a major contribution to the study of Australian politics, bringing to the task a scale and ambition more commonly associated with presidential history in the United States. The writing is unadorned, but happily eschews the kind of bloodless prose not unknown in academic political science. And Melbourne University Press has produced an immensely handsome volume under its Miegunyah imprint.

Comments powered by CComment