- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Medicine

- Custom Article Title: Robert Reynolds reviews 'How to Survive a Plague: The story of how activists and scientists tamed AIDS' by David France

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It has been an interesting month to read David France’s magisterial history of the AIDS crisis in the United States. As I sat down to the write this review, The Guardian reported that a Georgia state politician, Betty Price, had raised the possibility of isolating HIV positive individuals. ‘I don’t want to say the quarantine word ...

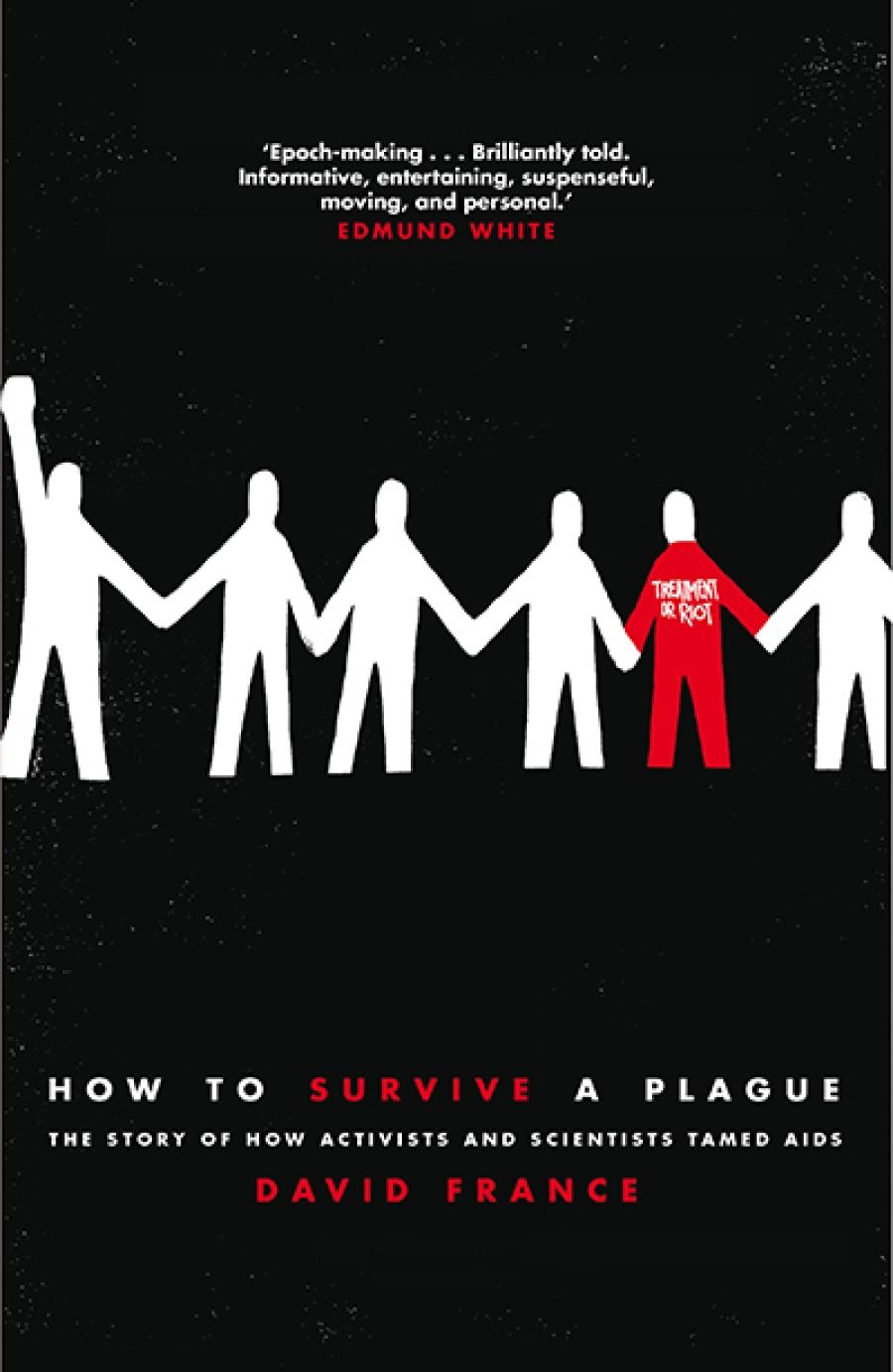

- Book 1 Title: How to Survive a Plague

- Book 1 Subtitle: The story of how activists and scientists tamed AIDS

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $34.99 pb, 640 pp, 9781509839391

If nothing else, these news items suggest that the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s has a long social, political, and cultural afterlife. David France’s How to Survive a Plague touches briefly on this legacy in a moving prologue and epilogue. For the most part, however, this book is a year-by-year depiction of the AIDS epidemic in the United States, from the first media stories of a strange illness afflicting gay men in July 1981 to the announcement of successful drug treatments that dramatically offered new hope to AIDS patients in January 1996.

France is a journalist and documentary maker who covered the epidemic from New York. This book comes in the wake of his 2012 Oscar-nominated documentary of the same name. It is hard not to miss the overlap with Randy Shilts’s book And the Band Played On (1987). Shilts was a journalist in San Francisco; his book covered the early years of the epidemic and was later made into an HBO movie. There are important differences, too: France’s narrative is based primarily in New York, Shilts wrote from San Francisco. In the mid-1980s, Shilts was writing in the midst of disaster; it shows in the urgency of his journalistic prose that verges occasionally on hectoring. France is more reflective and thoughtful. The emotional undercurrent of And the Band Played On is, I suspect, anger suffused by panic. In How to Survive a Plague, it is a more expansive, textured sadness. To put this another way, And the Band Played On is more of a polemic; How to Survive a Plague is history.

France is primarily concerned with the impact of the epidemic on American gay communities and their oft-heroic responses. This is well-trodden territory, not least by academics, memoirists, and novelists. The broad contours of the American AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, and the havoc it wreaked on gay communities, are familiar. After a decade of gay liberation and hard-won sexual bacchanalia, gay activists responded initially with scepticism at media reports of an illness felling sexually active gay men. France notes his own cynicism. ‘I was more annoyed than alarmed by the news. The story seemed like a new slander on the gay community, which had existed cohesively for barely more than a decade since the Stonewall Riots in 1968.’ As more gay men became sick and the often brutally quick and awful deaths mounted, gay activists organised community forums and action groups. In New York, the newly formed Gay Men’s Health Crisis led the charge. After initially resisting the idea that sex could transmit the illness, gay activists produced tentative information on how to minimise the risk of transmission. American and French scientists rushed to isolate the virus responsible for AIDS and became involved in an unseemly tussle over who discovered the human immuno-deficiency virus.

As the death toll spiralled, President Reagan studiously avoided mentioning AIDS by name and his administration chronically under-funded attempts to combat the epidemic. France recounts a chilling anecdote that aptly depicts Reagan’s criminally cavalier approach to the AIDS crisis. At a state luncheon for the visiting French president, the comedian Bob Hope made a crass joke about Rock Hudson’s death from an AIDS-related illness. Remember, Hudson had been a close friend of the Reagans and his death had attracted worldwide attention to the virus. France writes, ‘Mitterrand and his wife looked appalled. But not the Reagans. The first lady ... smiled affectionately. The president threw back his head and roared.’ Little wonder that AIDS activists in America became radicalised, tackling government, health researchers, and drug companies head-on, and inserting those living and dying with HIV into the forefront of the response to the virus.

David France accepts the Peabody Award for his 2013 documentary How to Survive a Plague, with Joy Tomchin (Peabody Awards, Wikimedia Commons)Evocative stories like the Mitterrand banquet litter How to Survive a Plague. The author’s great achievement is to populate the history of the American epidemic with individuals, to give an intimately human account of a public health crisis. He introduces a cast of characters and then weaves them in and out his 600-plus page account. At times, I wanted a glossary to remind me who was who, but for the most part the players become familiar. When they die, as many did, the reader registers their absence. Some die in dreadful circumstances, and it is the details that catch you in the throat. France writes of his neighbour, a handsome and once-strapping African American man who retired to his apartment after the death of his lover of twenty years. When he himself became perilously ill, he lay down on the floor and died alone. ‘After they removed his body, a dark outline remained permanently on the spot where he had lain.’

David France accepts the Peabody Award for his 2013 documentary How to Survive a Plague, with Joy Tomchin (Peabody Awards, Wikimedia Commons)Evocative stories like the Mitterrand banquet litter How to Survive a Plague. The author’s great achievement is to populate the history of the American epidemic with individuals, to give an intimately human account of a public health crisis. He introduces a cast of characters and then weaves them in and out his 600-plus page account. At times, I wanted a glossary to remind me who was who, but for the most part the players become familiar. When they die, as many did, the reader registers their absence. Some die in dreadful circumstances, and it is the details that catch you in the throat. France writes of his neighbour, a handsome and once-strapping African American man who retired to his apartment after the death of his lover of twenty years. When he himself became perilously ill, he lay down on the floor and died alone. ‘After they removed his body, a dark outline remained permanently on the spot where he had lain.’

France writes himself into the narrative, unobtrusively. By coincidence, he moved with a college friend to New York in June 1981, two weeks before the first brief mention in the New York Times of what later would be termed AIDS. This is the account of a participant-observer whose adult life unfolded in tragic times. France’s college roommate died of AIDS, as did numerous friends, acquaintances, a lover, and many of the familiar faces he passed on the streets of gay Manhattan. As David France concludes, for those of his cohort the plague will never be over.

Comments powered by CComment