- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: John Arnold reviews 'La Trobe: Traveller, writer, governor' by John Barnes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Victorians know the name La Trobe through the eponymous university, La Trobe Street in the city of Melbourne, and the Latrobe Valley in Gippsland. Tasmanians are familiar with the town of Latrobe in the north-west of their state. But how many are aware that all the above were named after Charles Joseph La Trobe, the first ...

- Book 1 Title: La Trobe

- Book 1 Subtitle: Traveller, writer, governor

- Book 1 Biblio: Halstead Press, $59.95 hb, 384 pp, 9781925043334

La Trobe’s Moravian upbringing and his belief in the ‘will of God’ were central to both his personal and professional life. Born in London in 1801, his father was a senior leader in the Moravian Church, and Charles and his siblings were educated in Moravian schools. As a young man La Trobe ‘rambled’ around Europe, producing two well-received books about his travels. He was particularly taken with the Alps area and Neuchâtel in Switzerland where he met his future wife, Sophie de Montmollin. In his early thirties, he travelled extensively around America, including periods with Washington Irving, and subsequently wrote The Rambler in North America (1835) and The Rambler in Mexico (1836). These, as with his other books, featured some of his own sketches, several of which are reproduced in this biography.

It was probably the strength of his writings that led to La Trobe being sent to the West Indies in 1837 by the Colonial Office to report on the education of emancipated slaves and their children. And it was most likely on the strength of his submitted reports that he was appointed in 1839 to be the superintendent of the new settlement at Port Phillip.

As there was no official government residence, La Trobe bought with him from England a pre-fabricated dwelling. He erected the house – now known as La Trobe’s Cottage – on the twelve and a half acres he purchased soon after his arrival just east of the city that he called Jolimont, after a hill bordering Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland.

The Moravian creed directed that its followers did not involve themselves in any public controversy. Charles La Trobe followed this principle while he was the administrator of Port Phillip, refusing to publicly rebut or even comment on the often vitriolic criticism of him in the Melbourne press. La Trobe was considered to be aloof, more European than English, rather than a man of the people. This was reinforced by his dislike of socialising for socialising sake and by his few close friends being those of the ‘gentlemen’ class of Melbourne. Due to his relatively low salary, he did not hold public balls or levees to commemorate major events.

Barnes devotes a full chapter to the treatment of the Indigenous Victorians during La Trobe’s time in the colony. The report card here is mixed. La Trobe believed that the local natives were primitive peoples whose only salvation was through conversion to Christianity. He was aware of the atrocities committed against them by squatters, but realised that it was near impossible to try and seek justice with magistrates and juries coming from the same class as the perpetrators.

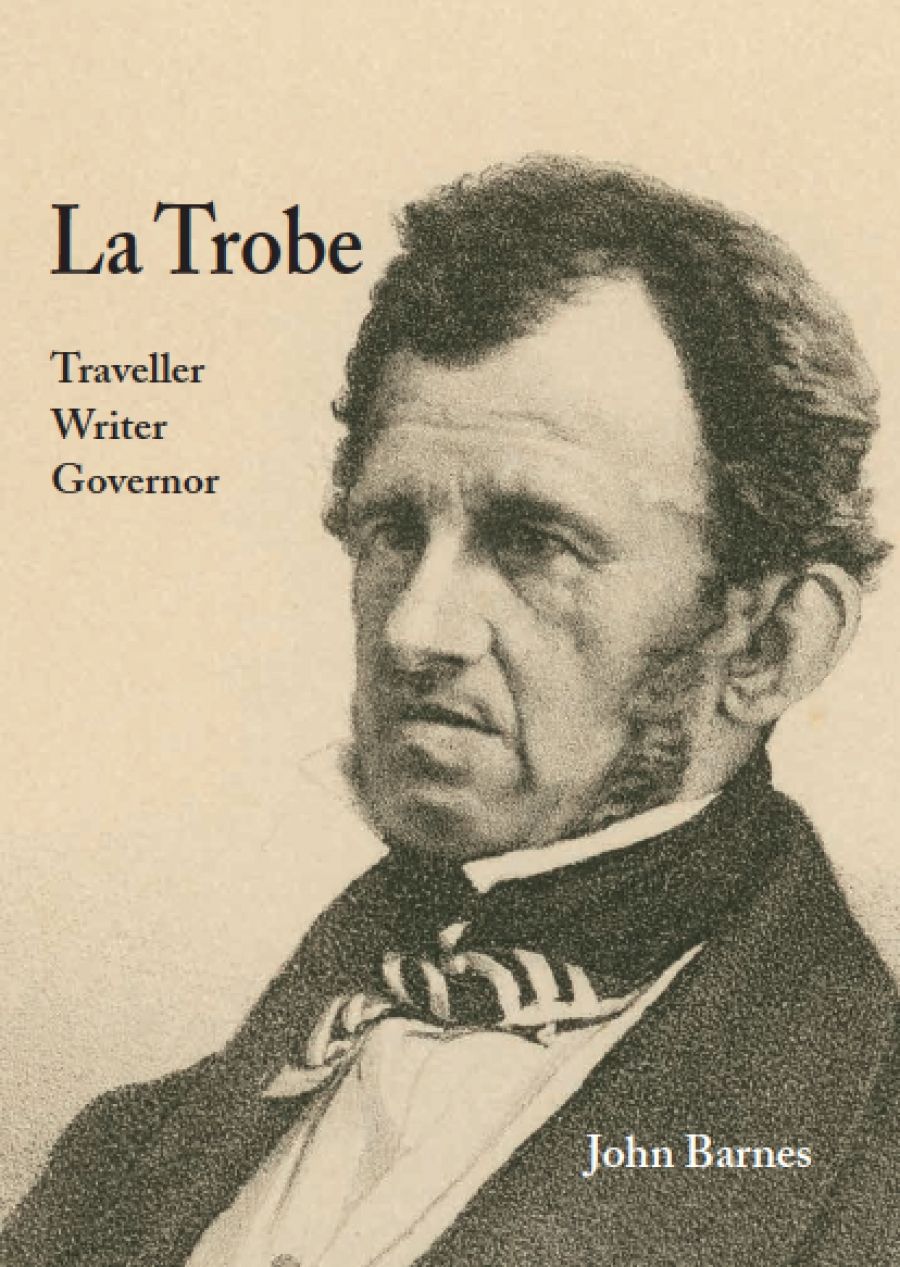

Portrait of Charles Joseph La Trobe, Francis Grant, 1855 (State Library of Victoria, Wikimedia Commons)In 1845 La Trobe sent his eldest daughter back to Europe to be educated. He assumed that he and the rest of the family would be following her within a year or two. But he stayed on after being appointed lieutenant-governor of the new state of Victoria. His governorship coincided with the discovery of gold. The resulting excitement and turmoil put enormous pressure on La Trobe and his administration. He feared anarchy and came close to a physical breakdown under the pressure of the extraordinary times. However, after a year or so things stabilised, for which, Barnes argues, La Trobe can take some credit. In December 1852 he submitted his resignation. His wife, suffering from poor health, had already returned to England with their remaining children.

Portrait of Charles Joseph La Trobe, Francis Grant, 1855 (State Library of Victoria, Wikimedia Commons)In 1845 La Trobe sent his eldest daughter back to Europe to be educated. He assumed that he and the rest of the family would be following her within a year or two. But he stayed on after being appointed lieutenant-governor of the new state of Victoria. His governorship coincided with the discovery of gold. The resulting excitement and turmoil put enormous pressure on La Trobe and his administration. He feared anarchy and came close to a physical breakdown under the pressure of the extraordinary times. However, after a year or so things stabilised, for which, Barnes argues, La Trobe can take some credit. In December 1852 he submitted his resignation. His wife, suffering from poor health, had already returned to England with their remaining children.

While waiting for the arrival of his successor, Charles Hotham, La Trobe read in the English newspapers that his wife had died not long after she had arrived in England. The family letters informing him of her death had been sent on a faster ship but it was delayed, arriving after the one carrying the latest English papers. His belief in the will of God again carried him through, as it did when he went blind in his sixties.

La Trobe was confident that he would be offered another position in the colonial service after he returned to England. But none was forthcoming. He did not have powerful connections amongst the upper and ruling élite, nor did he have a military background, often one of the key criteria for colonial governors. The fact that he married his deceased wife’s widowed sister would not have helped. In addition, the strong criticisms made of his administration, especially those regarding his handling of the gold diggers in 1852–53, made by the respected William Howitt in his Land, Labour and Gold (1855), possibly influenced English bureaucratic opinion of the former governor.

After his forced retirement, La Trobe and his wife and their children along with those from his first marriage, lived comfortably in England, with frequent visits to Neuchâtel. He became a retired man of letters pursuing his intellectual interests, including a planned book on Victoria that never eventuated, and rambling locally. He remained in contact with close friends in Victoria especially those who administered his affairs relating to the sale of the Jolimont land. He was belatedly granted a civil pension in 1864 and died eleven years later.

The magnificent Domed Reading Room in the State Library is now called the La Trobe Reading Room. The library and Melbourne University (he co-founded both with Redmond Barry), and the gardens surrounding Melbourne, particularly the Royal Botanic Gardens, which he reserved as Crown Land, are enduring legacies of La Trobe’s fourteen years in Victoria.

Published by a small independent publisher, La Trobe: Traveller, writer, governor is a long book, around 200,000 words, a length that that may limit its readership. But it is the first comprehensive biography of La Trobe and will become the standard work.

Comments powered by CComment