- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Bruce Moore reviews 'That’s the Way It Crumbles: The American conquest of English' by Matthew Engel

- Custom Highlight Text:

Matthew Engel has written for many years in The Guardian and the Financial Times, on topics ranging from politics to sport, and between 1993 and 2007 he produced editions of Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack. In this latest book he takes up the bat (or steps up to the plate) for British English. That’s the Way It Crumbles is a lament ...

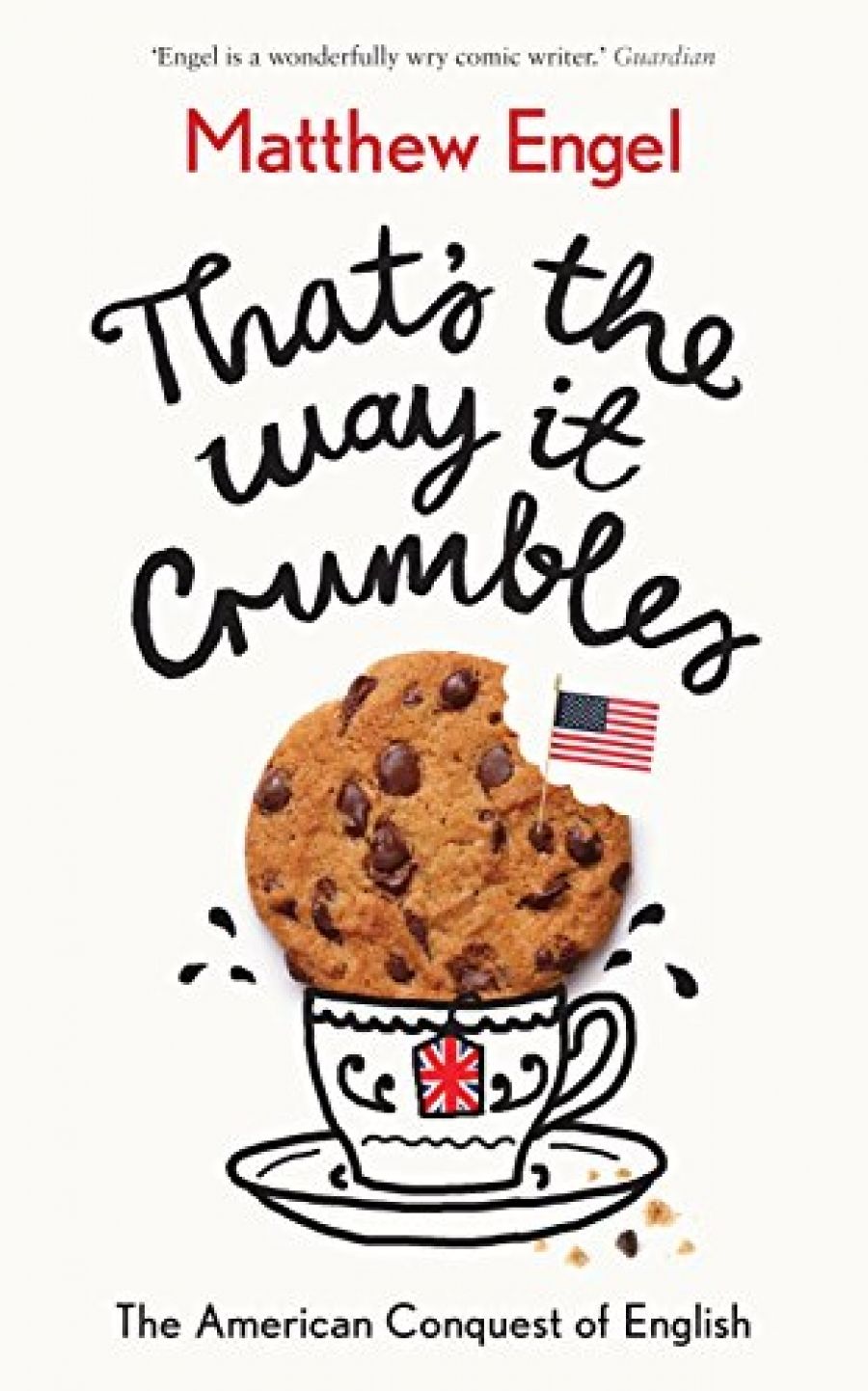

- Book 1 Title: That’s the Way It Crumbles

- Book 1 Subtitle: The American conquest of English

- Book 1 Biblio: Profile Books, $32.99 hb, 278 pp, 9781781256688

The earliest imports from the Americas (sometimes via Spanish) included the typical colonial borrowings for flora and fauna (moose, raccoon, maize, tobacco), as well as English-based formulations such as pipe of peace. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, new English coinages (such as belittle) or English words with new or altered meanings (such as awful in its shift from ‘inspiring awe’ to ‘frightful, very ugly’) start to be noted as barbaric Americanisms.

These imports, however, were not great in number until the twentieth century. Between the world wars they increased greatly, partly due to the increasing Americanisation of popular culture through films (or movies) and music. In this period a vast number of Americanisms became settlers in Britain: beautician, brass tacks, cafeteria, chip on one’s shoulder, frazzled, gentlemen’s agreement, goner, hell-bent, keeping up with the Joneses, milk shake, moron, no kidding, rush hour, showdown, snowed under, white collar, wisecrack, yes-man. From a later perspective, these all seem remarkably commonplace, but they aroused passion when they first claimed their visas, so much so that in the 1931 election campaign Stanley Baldwin explained his support for protectionism in trade in these terms: ‘My personal reason for being a Protectionist is that I may help to banish from this country the American language.’

American economic and political power and the control of international popular culture coincided with the increasing globalisation of English. The lexical onslaught continued after World War II. Some of the words imported in the early part of this period were unobjectionable, since they ‘reflected new technologies, new problems, new beliefs’. But from the 1980s onwards American words were gobbled up in a sloppy and undiscriminating manner, such that Britain ‘handed over control of its culture and vocabulary to Washington’. Engel laments: ‘A nation that outsources the development of its own language ... is a nation that has lost the will to live.’ There are minor victories, such as mobile phones holding out against cellphones. But where are the defending troops? Where is Dad’s Army? Who will rid us of these meddlesome bluebirds?

For a time, the BBC was the defender of Britishness, although Engel is sharply cognisant of the ironies here. BBC English entrenched class divisions and ignored regional variation in the language, making it an easy target for the brashly democratising Americanisms. The only contemporary linguistic evidence of a fightback is perhaps in the youth dialect called Multicultural London English, with its combination of black British vernacular, traditional working-class slang, and other migrant elements (coz, bare, extra, innit, you woz). But youth slang of this kind is unlikely to become mainstream. In some despair, Engel looks to Brexit as a possible sign of ‘the emergence of a constructive nationalism’, in which British English will also experience renewal.

In reading Engel’s book I was reminded of the fact that British English has survived many lexical onslaughts in the past. It took many words from the Viking invaders, to whom we owe the pronouns they and them. The Normans and the French delivered more than 10,000 words. Such invasions enriched British English and fostered its propensity to borrow from other languages in order to expand its word-stock. When this richness was coupled with political and economic power, British English triumphed beyond its island boundary. Was it this global imperialism, and the subsequent role of British English as the ‘default’ variety of English, that led, ironically, to a diminution of the Britishness of British English? Whatever the case, the willingness to take up Americanisms is consistent with the history of British English, and with its role as the ‘default English’.

Australian English now naturalises Americanisms with little evidence of the complaint tradition that continues in Britain, and Australian English has in its arsenal a series of key cultural terms that embody Australian values (battler, bludger, dinkum, and the like). Does British English still possess comparable cultural terms? Perhaps not, when even stiff upper lip, as Engel points out, proves to be an Americanism.

The battle may be lost, but Engel takes us on a witty and thoroughly enjoyable journey through the alarums and skirmishes that have brought British English to its present malaise.

Comments powered by CComment