- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

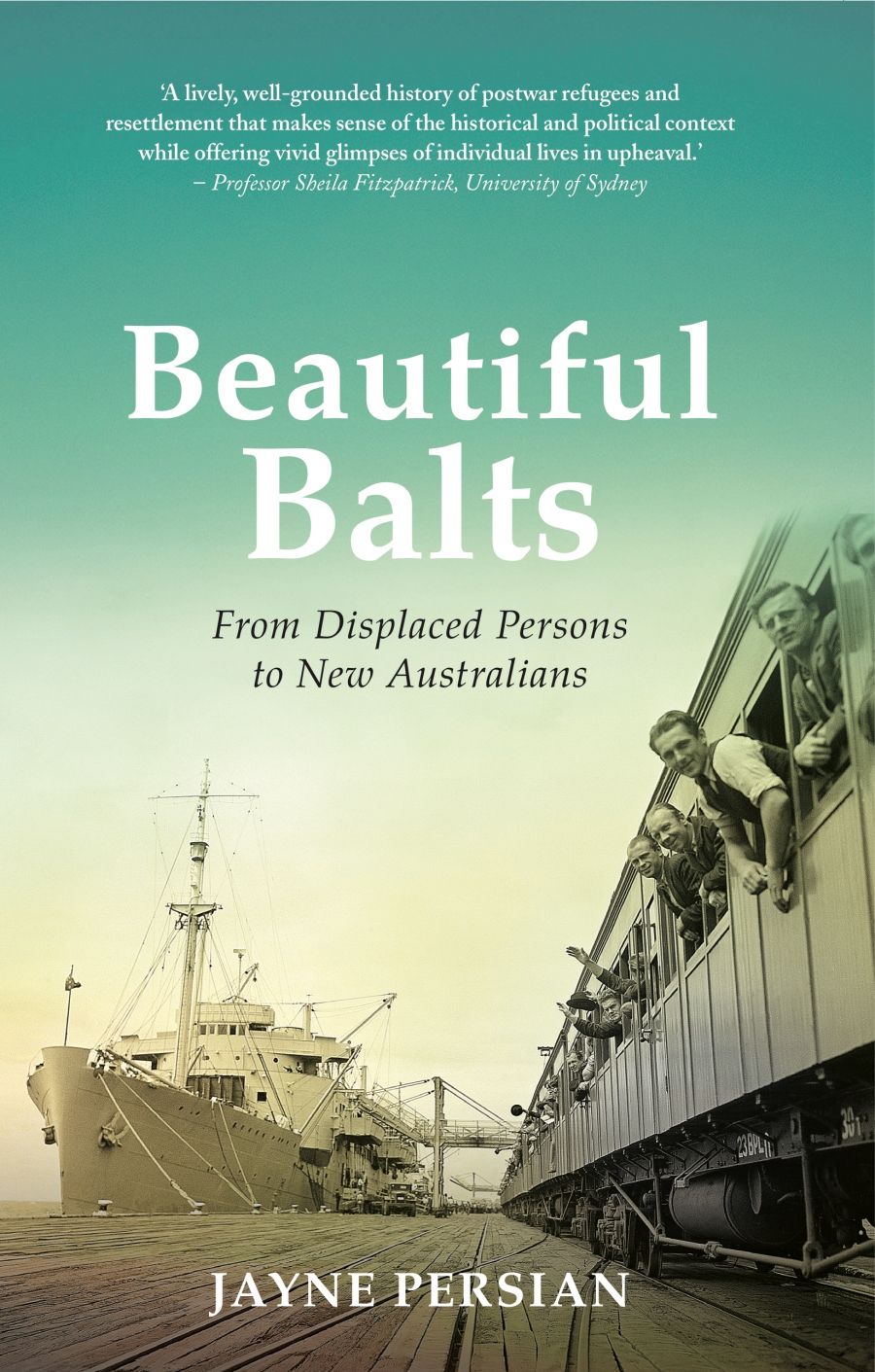

- Custom Article Title: Francesca Sasnaitis reviews 'Beautiful Balts: From displaced persons to new Australians' by Jayne Persian

- Custom Highlight Text:

I grew up in a New Australian household, and admit at the outset to a biased view. My Lithuanian-born parents were actual Baltic immigrants among the other nationalities referred to by the blanket designation ‘Balt’. Much of the anecdotal material of Jayne Persian’s Beautiful Balts was deeply familiar to me from childhood ...

- Book 1 Title: Beautiful Balts

- Book 1 Subtitle: From displaced persons to new Australians

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 250 pp, 9781742234854

Persian begins her chronology of the first wave of non-Anglo-Celtic postwar migration with the dramatic story of her husband’s Cossack grandparents, the first ‘displaced persons’ story she had heard, and the recounting of which stands in for the Eastern European migrants’ experience of mass devastation and dislocation prior to resettlement in Australia. I can understand why Persian does not dwell on this back-story. If, as W.G. Sebald suggests in The Emergence of Memory (2010), we are inured to images of horror, there is no benefit in repeating what is familiar to the point of dreariness.

What Persian does demand of the reader is an attention to the inconceivable numbers of people involved: twelve million or more displaced persons (DPs) who were stranded outside their own countries by the end of the European conflict in 1945. Imagine, if possible, the logistics of providing welfare and housing for that many disparate nationalities – Poles, Ukrainians, Russians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Hungarians, Yugoslavians, Romanians, Bulgarians, Albanians – concentration camp survivors, forced labourers, civilian evacuees, and ex-prisoners of war. This in a country devastated by Allied bombing; a Germany that was struggling to feed and house its surviving civilian population. No wonder the Allied authorities were keen to repatriate as many of these problematic DPs as quickly as possible, avoiding at all cost the ‘permanent status’ implied by the term ‘refugee’. That DPs, fearing execution or deportation to Siberian labour camps if returned to Soviet-occupied territories, were not taken seriously is an indictment of the entire situation.

Between 1947 and 1952 more than 170,000 DPs were granted asylum in Australia. In effect that meant two years’ indentured labour in exchange for assisted passage. In a shrewd piece of propaganda, then Minister for Information and for Immigration Arthur Calwell, with Prime Minister Ben Chifley, sold these ‘Beautiful Balts’ to an insular, monolingual society as blond, blue-eyed, hard-working candidates for assimilation: that is, as racially (Aryan) and politically (anti-communist) suitable and, less publicly, as a cheap labour force in places where Anglo-Australians were unwilling to go.

What surprised me, though perhaps it should not have, was the degree to which the Australian recruiting missions in Europe were actively anti-Semitic, excluding those most in need of compassion. Like many of their compatriots, my parents chose to believe the myth of humanitarianism over economic imperative, and maintained their eternal gratitude to the Australian people for giving them sanctuary. Others, interviewed by Persian, were more vocal in their criticism of the conditions of their migration.

1947 poster by the Commonwealth Department of Information, selling Australia as the land of 'industry and sunshine' (image from book)

1947 poster by the Commonwealth Department of Information, selling Australia as the land of 'industry and sunshine' (image from book)

Rebranded by Calwell as ‘New Australians’ in another piece of astute labelling to counter the derogatory connotations of ‘refo’ and ‘balt’, and despite positive propaganda promulgated by newspapers supporting the Labor government initiative, the DPs’ lived experience, and their intellectual capabilities and qualifications, were consistently ignored. They were required to work as labourers or domestics wherever they were needed. Families were often split up, with little consideration given to their emotional or mental health. Of course, at that time, ‘trauma counselling’ was not offered to Australian returned servicemen either.

In what amounts to a brief afterword, Persian mentions the current condition of asylum seekers, but misses the opportunity to engage with the question that dogs the pages of Beautiful Balts: ‘Is there something we can learn from [using a refugee crisis for national gain] when today’s refugee policies seem so uncompromising?’ Sadly, all we learn is that governments are rarely swayed by altruistic considerations.

Loss, longing for ‘home’, nostalgia, and guilt figure large in narratives of mass displacement. ‘Home is the return to where distance did not yet count,’ wrote John Berger (And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos, 1984), referring to the political, cultural, and geographic factors which contribute to a permanent sense of displacement and dissociation. That is especially true of DPs, or refugees, to give them their rightful status, for whom the return to an idealised homeland is impossible; for whom the result is the burden of perpetuated sorrow.

Beautiful Balts is the offshoot of a doctoral thesis ‘centred on memory and commemoration and, particularly, oral history interviews’. Although the scholarship is undoubtedly sound (the notes and index run to forty-seven pages), Persian’s version of events does not transform into a compelling narrative. My inclination is to compare my family’s stories with how she has chosen to relate the history of this period, confirming my advocacy for a more intimate and impassioned approach. History is, after all, a matter of perspective, the primary sources and the chronologies merely the scaffolding upon which narratives are constructed.

Comments powered by CComment