- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Amanda Nettelbeck reviews 'The Good Country: The Djadja Wurrung, the settlers and the protectors' by Bain Attwood

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Good Country begins in February 1840 with a cross-cultural encounter in Djadja Wurrung country, now central Victoria. Two Protectors of Aborigines, recently appointed to the burgeoning pastoral district around Port Phillip, met with an Aboriginal group camped near Mount Mitchell. At this time, the Aboriginal protectorate had been operating for little ...

- Book 1 Title: The Good Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Djadja Wurrung, the settlers and the protectors

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $29.95 pb, 239 pp, 9781925523065

Within a decade of this encounter, the Port Phillip protectorate had closed, undermined by other government priorities and declining administrative faith in Aboriginal people’s transition to colonial subjecthood. Dispossession and introduced diseases wrought havoc on the Djadja Wurrung, and by the 1860s they and other Kulin peoples were being gathered onto mission stations under the oversight of a Central Board. After this time across Australia’s colonies, programs of protection were redefined around legislative measures that abandoned an earlier rhetoric of Aboriginal people’s legal rights and made them wards of the state. It would be well into the next century before the civil rights era signalled a shift in Aboriginal people’s perceived place in the nation, although they had continuously sought rights and recognition. When Nandelowwindic described his country to the Protectors in February 1840, this long cycle of alienation from land and the imposition of state control over Aboriginal lives had not yet worked its devastating impacts in Djadja Wurrung country, although it had begun.

From this distant encounter, Bain Attwood asks his readers to consider the colonial experience from the position of the Djadja Wurrung, whose secure place in their own land was subjected to radical upheaval. Readers of Attwood’s extensive scholarship on Aboriginal Australia might recognise the provenance of this book in a smaller, earlier work published as My Country: A history of the Djadja Wurrung (1999), the result of research undertaken for the Dja Dja Wurrung Aboriginal Corporation. But The Good Country is much more than an expanded version of that earlier work. The larger history it tells is of a complex, multi-layered relationship between different groups whose interests were primarily competing but sometimes came into alignment: the Djadja Wurrung whose country was overtaken by pastoralism, the settlers who laid claim to it, and the colonial officials who were appointed as mediators. Significantly affecting this three-way relationship were the movements of neighbouring Aboriginal clans, with whom the Djadja Wurrung shared ancient trade networks, communication lines and rivalries. This pre-existing world of Aboriginal politics was unsettled by colonisation and, in turn, triggered shifts in the fragile balance of colonial relationships.

Some of the competing expectations and difficult proximities that underpinned this culture of the pastoral frontier were visible in events that occurred on Henry Munro’s Mount Alexander station a month before Robinson and Parker’s encounter with Nandelowwindic’s group. In January 1840, several groups coalesced on or around Munro’s station. The Djadja Wurrung, facing increasing hunger as pastoralism took over their country, expected a display of reciprocity from the settlers in their midst. Their rival neighbours, the Daung Wurrung, were camped nearby, their unfamiliar presence adding a new element of tension. Munro and his men were nervous, their limited capacity for conciliation ready to give way to violence. The Protectors Robinson and Parker were on hand, but they carried little authority with the pastoralists. The Border Police arrived, escalating rather than diminishing the potential for resort to force. A circumstance that might have resolved peacefully erupted into open conflict, and at least one Aboriginal man was killed.

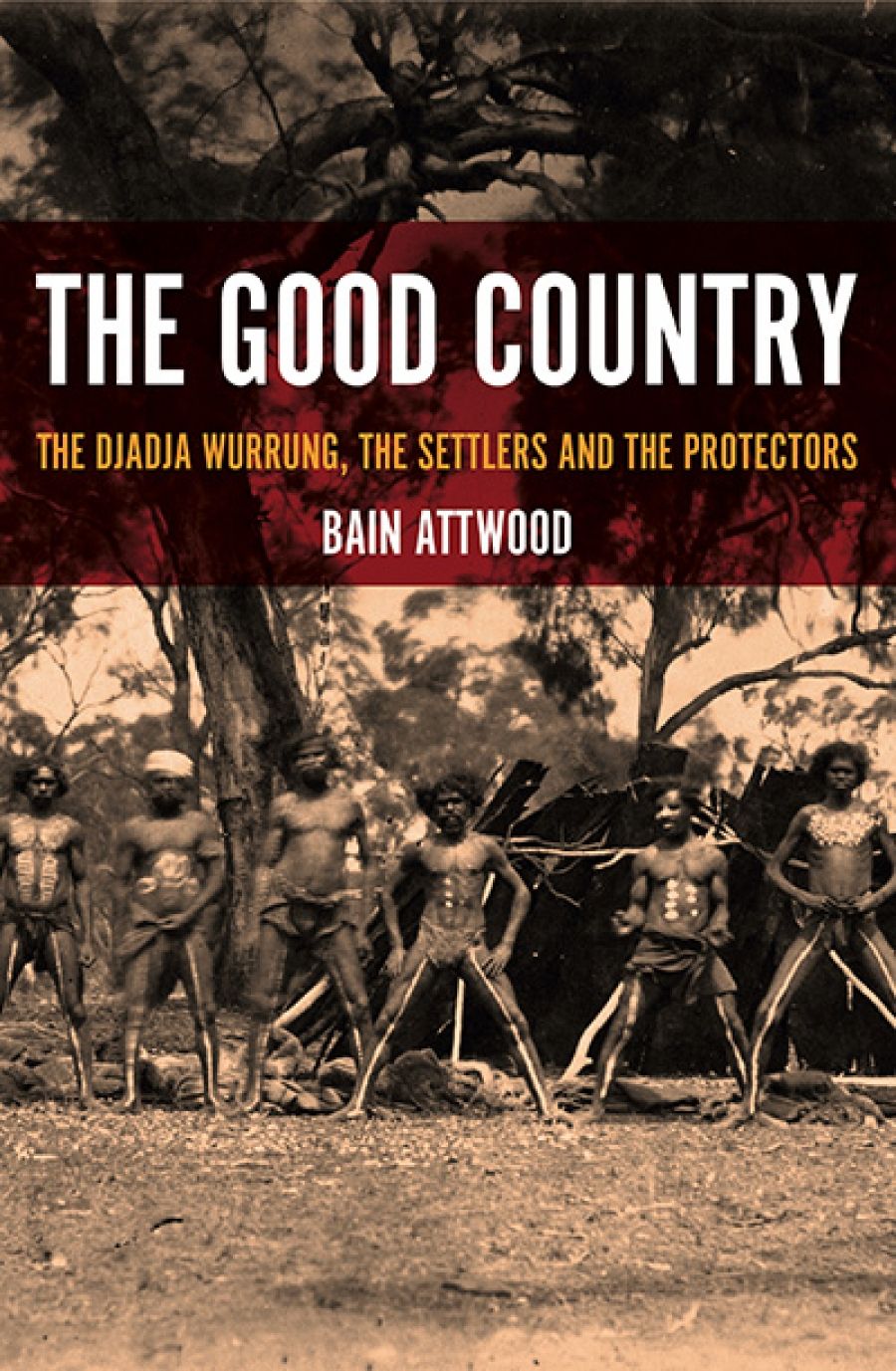

Djadja Wurrung Farmers, Franklinford, Victoria, 1858 (State Library of Victoria, Wikimedia Commons)

Djadja Wurrung Farmers, Franklinford, Victoria, 1858 (State Library of Victoria, Wikimedia Commons)

Despite a series of such clashes, Attwood illustrates that conflict in Djadja Wurrung country was more contained than in some other districts, its counterpart being relatively harmonious relations. In explaining this, he stresses the importance of local conditions. Most clashes in the district occurred on a limited number of stations, often involved the same protagonists, and arose from specific environmental factors and pastoralist attitudes. Beyond these conditions, the spread of pastoralism unfolded at a slower pace than in many parts of the colony, creating some scope for Djadja Wurrung and pastoralists to explore terms of cooperation. This, then, is a deep local history that pays attention to the forces of time and place to explore how colonial relations evolved as they did in this region, and how Aboriginal people responded to the successive colonial processes of dispossession, institutionalisation, and assimilation. Ultimately, the Djadja Wurrung survived those processes, notwithstanding profound changes to their world. While it is deeply regional, many aspects of this history are mirrored elsewhere in the wider story of colonisation across the continent, and in the everyday relationships behind it.

In The Good Country, detailed archival research is coupled with incisive reflection on the contemporary problem of how we understand and ‘own’ the past. This combination of strengths is familiar to readers of Bain Attwood, who has contributed more to tracing the histories of Australia’s colonial experience and Aboriginal rights than perhaps any other historian of his generation. Having opened with an early colonial encounter, The Good Country closes with a set of questions about colonisation’s continuing afterlives and their meaning for Dja Dja Wurrung people today. Here, Attwood suggests that the early aim of reconciliation programs to articulate a ‘shared’ or unified history might usefully be turned to an aim of ‘sharing histories’, allowing for the contingencies of who speaks, different kinds of historical knowledge, and an absence of neat resolutions. The Good Country furthers this aim by grappling at close range with the complexities of colonial relations and their contested legacies. At a time when how we remember and memorialise the past remains at issue in the public domain, this task is more relevant than ever.

Comments powered by CComment