- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Gemma Betros reviews 'Flaubert in the Ruins of Paris: The story of a friendship, a novel, and a terrible year' by Peter Brooks

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

As we approach the end of what might be considered another pretty terrible year, it’s worth being reminded that every age has its tribulations ...

- Book 1 Title: Flaubert in the Ruins of Paris

- Book 1 Subtitle: The story of a friendship, a novel, and a terrible year

- Book 1 Biblio: Basic Books, $45 hb, 264 pp, 9780465096022

The year in question began in July 1870 with France’s misguided declaration of war on Prussia, and ended with the brutal destruction of the Paris Commune in May 1871. In between came the fall of Napoleon III (nephew of Napoleon I), the declaration of the Third Republic, and the siege of Paris by the Prussian Army. Although a newly elected conservative government negotiated peace with Prussia, its terms – demanding reparations from France and the ceding of territory in Alsace and Lorraine – created such a sense of betrayal among Parisians and the National Guard that they hounded the government from the capital, replacing it with the radical Paris Commune. The government regained control only when the French Army invaded Paris in a blood-filled week that saw the city in flames and some 20,000 Communards executed.

For Gustave Flaubert, author of the bestselling Madame Bovary (1856–57), this was a year of horror, a sentiment he shared with writer George Sand. The two corresponded regularly, their letters marked by honesty, support, and often tenderness. Their politics were as different as their novels – Sand was a socialist, Flaubert an élitist – but their views became more aligned as Sand condemned the Commune for opposing the legitimate republican government and as Flaubert began to see a republic as the only means by which France might achieve stability.

Flaubert’s horror stemmed not so much from the ravages of war as from the irrationality of his compatriots as they turned first on the Prussians, and then, one another. ‘The odour of the corpses disgusts me less than the swamps of egotism exhaling from all mouths,’ he reported to Sand. Like many, Flaubert travelled to Paris after the Commune’s fall to witness the city’s devastation, lamenting to a friend that if only more people had read his novel Sentimental Education, ‘none of this would have happened’.

Published in late 1869, Sentimental Education was conceived as the story of Flaubert’s own generation, one that had come of age in the momentous year of 1848 when revolution had swept through Europe and installed in France a second republic. The novel follows Frédéric Moreau from lovestruck student to middle-aged failure. Perpetually distracted by his love life, Frédéric misses his role in history, remaining a passive observer at the edge of the events transforming his world.

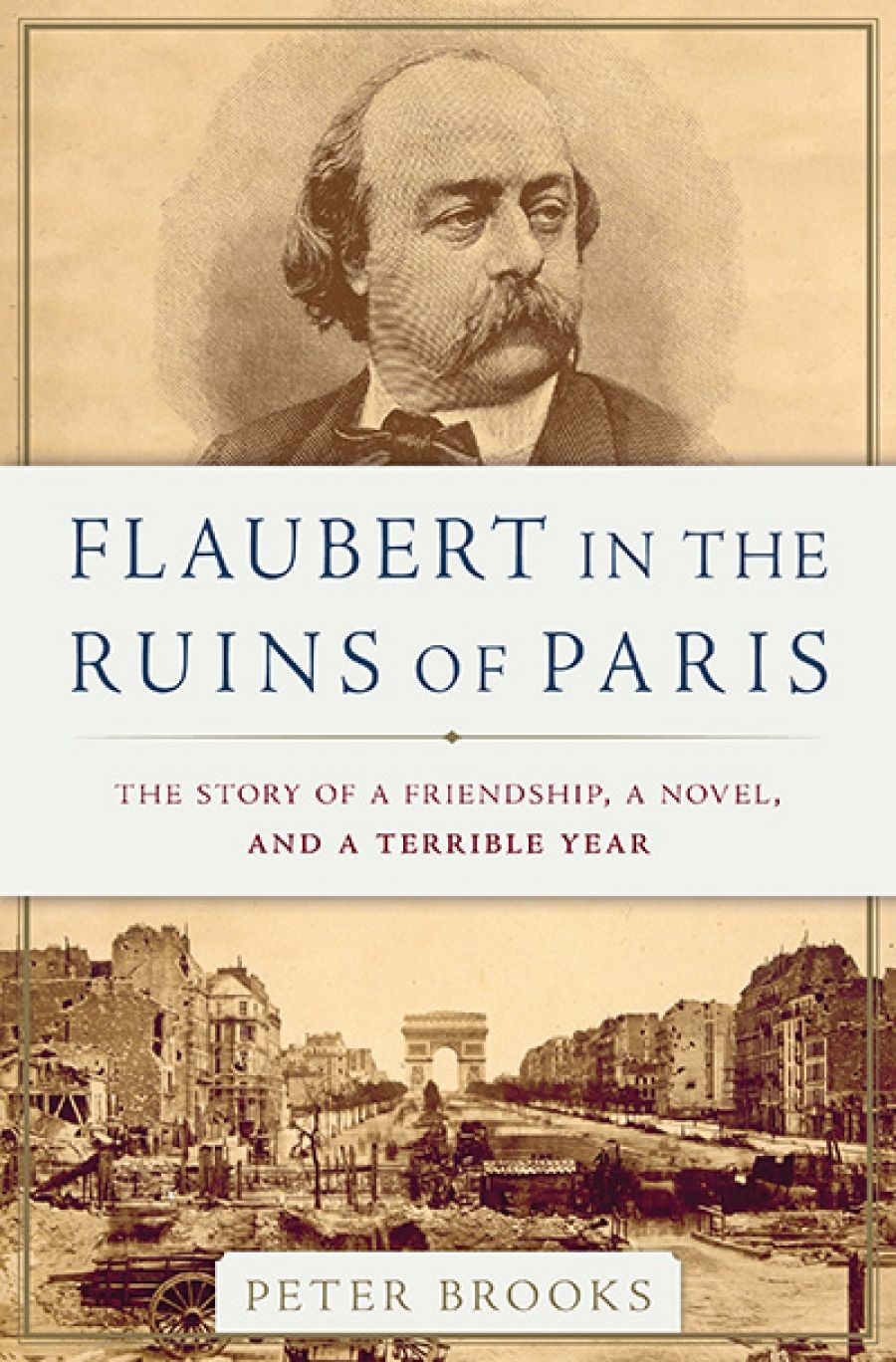

Gustave Flaubert (Wikimedia Commons)

Gustave Flaubert (Wikimedia Commons)

Why did Flaubert think that his novel about one insurrection could have prevented another? Reviewers disliked the indolent Frédéric, unable to recognise in his ineptitude the author’s own exasperation with the political developments of his age. ‘The current folly is the result of too much stupidity,’ he wrote to Sand, ‘and this stupidity came from an excess of jokery. From too much lying we became idiots.’ The universal suffrage of 1848 had ushered in not a better society but Napoleon III, a rotten leader who had set France, yet again, on a path to devastation and created a regime in which, Flaubert declared, ‘everything was fake’. He predicted that a similar anti-liberal reaction would follow this new upheaval, and again bring in ‘a conservative regime of a reinforced stupidity’.

Brooks perhaps takes Flaubert’s claim about his novel too seriously, but it is an effective starting point for exploring what he terms ‘the novelization of history’. Although a historical novel, Sentimental Education represented a departure from the genre by dealing with recent history as experienced by those who lived through it: to ensure accuracy Flaubert spent much time gathering eyewitness accounts. Importantly, he endowed the young Frédéric with the ambition to ‘one day be the Walter Scott of France’ (a line Brooks does not discuss), an ambition that quickly recedes. Flaubert’s interest lay not in romanticism but in realism, and in showing, suggests Brooks, ‘what is at stake for the individual amid the forces of history.’

Brooks offers a masterful introduction to nineteenth-century France, stretching from its literary and political worlds, to its photography, to the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur, built in a confused attempt to expiate the past. In his account of the Commune, we smell the fires smouldering throughout Paris, hear executions taking place, see blood on the streets, and wonder about the taste of salami de rat, part of the diet of so many besieged Parisians. He also shows how Flaubert’s changing political views played out in the author’s subsequent writings, tracing here the crucial influence of Sand, a writer whose personal life too often still distracts from her work.

The French Revolution had set a blueprint for how the unhappy might try to achieve change: Brooks’s own experiences of the 1968 student revolution in Paris, recounted in the epilogue, remind us just how long it has endured. A novel was never going to prevent the events of 1870–71, but in crafting from an individual life history a cautionary national one, Flaubert sought to excavate the truth behind the dream. While the French Revolution had given birth to new ideologies, it had also fractured them in a way that meant political stability in nineteenth-century France would remain an illusion.

Comments powered by CComment