- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Kerryn Goldsworthy reviews 'Atlantic Black' by A.S. Patrić

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Writing this review in the first week in November, I look at the calendar and note that we are a few days away from the seventy-ninth anniversary of Kristallnacht, when, over the two days of 9–10 November 1938, at the instigation of Joseph Goebbels, there was a nationwide pogrom against German Jews that saw synagogues, business premises, and private ...

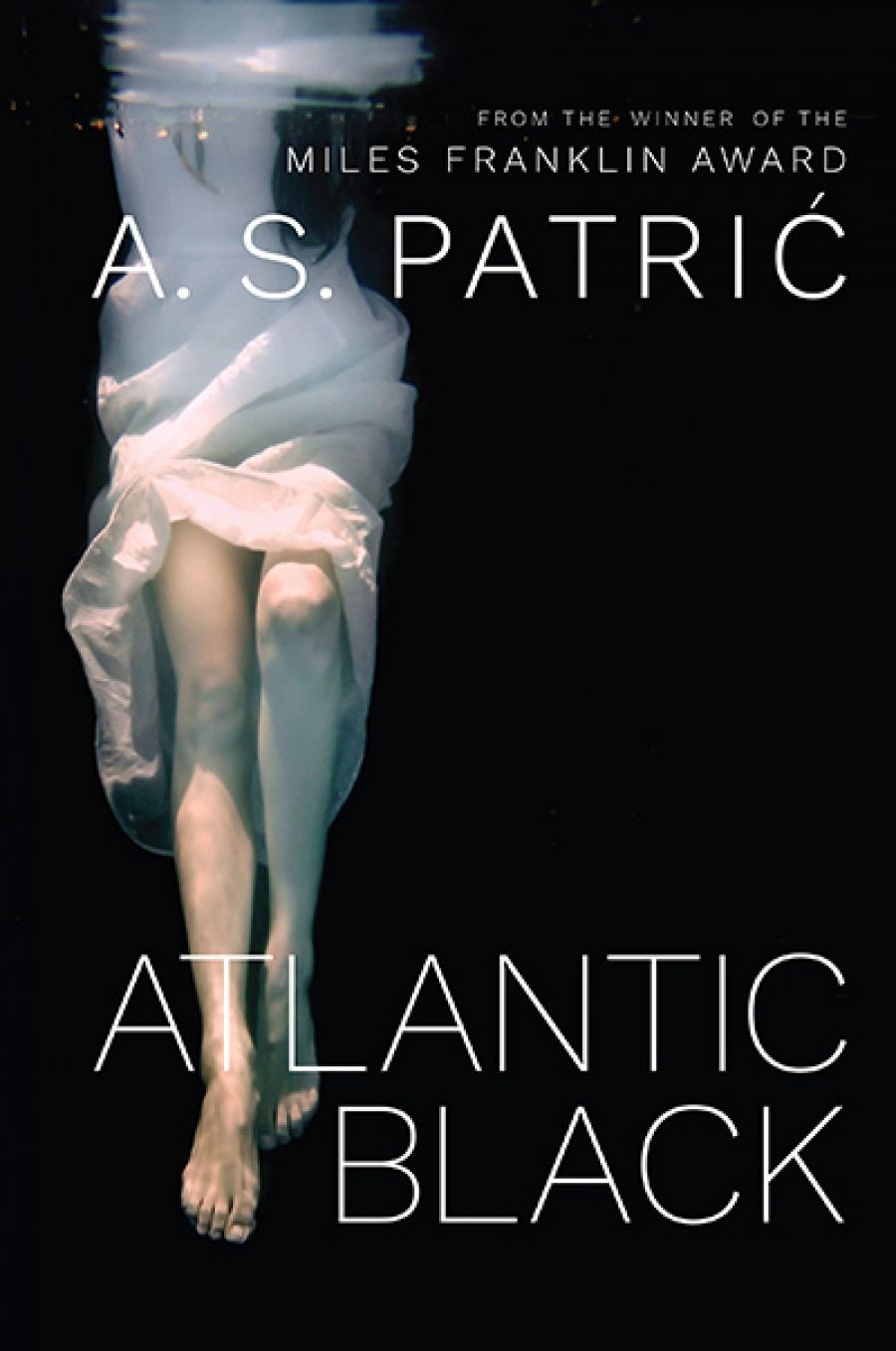

- Book 1 Title: Atlantic Black

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.99 pb, 280 pp, 9780995409828

Patrić’s name was not entirely unfamiliar in Australian literary circles, but it suddenly became much better known when he won the Miles Franklin Literary Award in 2016 for his first full-length novel, Black Rock White City (2015). Much was made by commentators of this being a ‘début novel’, but he had published three earlier forays into fiction, the short-story collections The Rattler and Other Stories (2011) and Las Vegas for Vegans (2012), and the novella Bruno Kramzer (2013). Each of these shows the technical sophistication and intellectual heft that characterised Black Rock White City, and those things are apparent again in Atlantic Black.

Katerina Klova is seventeen, the daughter of the English Anne and the Russian diplomat Audrius. Katerina and her mother are travelling from their most recent home, in Mexico, to France, where they will meet up with him and with Katerina’s brother Kornél. She has memories of living in other cities: Leningrad, Lisbon, Warsaw. They are travelling in direct defiance of Audrius’s wishes, and there’s a strong hint that he knows – as a diplomat would – what is about to be loosed upon the world: ‘In the handbag are the keys to the house in Mexico that they might never see again. Audrius had been clear in a telegraph: Do not sell. Do not leave. He’d been away for two years. The next telegraph that came through was even clearer: STAY.’

Small but ominous things happen to Katerina in a steady stream from the beginning of the book. She slips on the deck and falls over. She sees a man at the ship’s rail who seems to be contemplating suicide. She is bitten by one of her father’s borzois, travelling in cages in the bowels of the ship. She sees a Great War veteran who has lost a leg; then she sees a dead body. And all of this happens before we find out, still quite early in the novel, that her mother, her travelling companion, has had some sort of psychotic break, leaving Katerina – a seventeen-year-old girl on a ship full of strangers on New Year’s Eve – entirely to her own devices. ‘With her mother in the infirmary time has opened up, become strange and uncharted.’

A.S. Patrić (photograph by Bleddyn Butcher)The disintegration continues, exacerbated by the strangeness of New Year’s Eve. Patrić has mentioned the influence of Stefan Zweig’s novella The Royal Game (1941) on his own novel, but what it kept reminding me of was Patrick White’s The Aunt’s Story (1948), with its stylised and near-hysterical narrative fragmentation mirroring the disintegration of Europe in wartime. Bad things continue to happen to Katerina, and the downward spiral is formally marked as she reads some letters that her mother has been keeping from her.

A.S. Patrić (photograph by Bleddyn Butcher)The disintegration continues, exacerbated by the strangeness of New Year’s Eve. Patrić has mentioned the influence of Stefan Zweig’s novella The Royal Game (1941) on his own novel, but what it kept reminding me of was Patrick White’s The Aunt’s Story (1948), with its stylised and near-hysterical narrative fragmentation mirroring the disintegration of Europe in wartime. Bad things continue to happen to Katerina, and the downward spiral is formally marked as she reads some letters that her mother has been keeping from her.

With its costumes and its traditional loosening of conventions, this shipboard New Year’s Eve has about it a kind of dark carnivalesque feel, a sense of licensed disorder. Katerina, for reasons that remain murky, has decided to put on her brother’s dress uniform, and roams the ship in this outfit. Katerina is in drag, her mother is in a straitjacket, her brother is in trouble, and she hasn’t seen her father for two years: this family is splintering. As with Patrić’s earlier prose fictions, there’s something dreamlike and heightened about the world created in this book, with an edge of nightmare. It is too stylised and strange to be thought of as any sort of standard realist fiction; the dialogue alone is formal, sophisticated, and hectic well beyond any real conversation. The whole novel is like an Expressionist painting, with impending disaster just beyond the horizon.

Whether you regard this novel as ‘historical fiction’ depends entirely on what you think that is. Some people think of bodice-rippers; others think of historical fiction as something whose main concern is the public events being lived through during the period in which the novel is set. My definition of historical fiction is any fiction set more than a generation earlier than the period in which it is being written, and good historical fiction always shines a light on the world we live in now, and the way we live in it. Certainly we have never, in my lifetime, had more reason to fear an impending and engulfing international disaster than we do at the moment, and it’s very clear that Patrić’s real subject in this book is the current state of the world.

Comments powered by CComment