- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

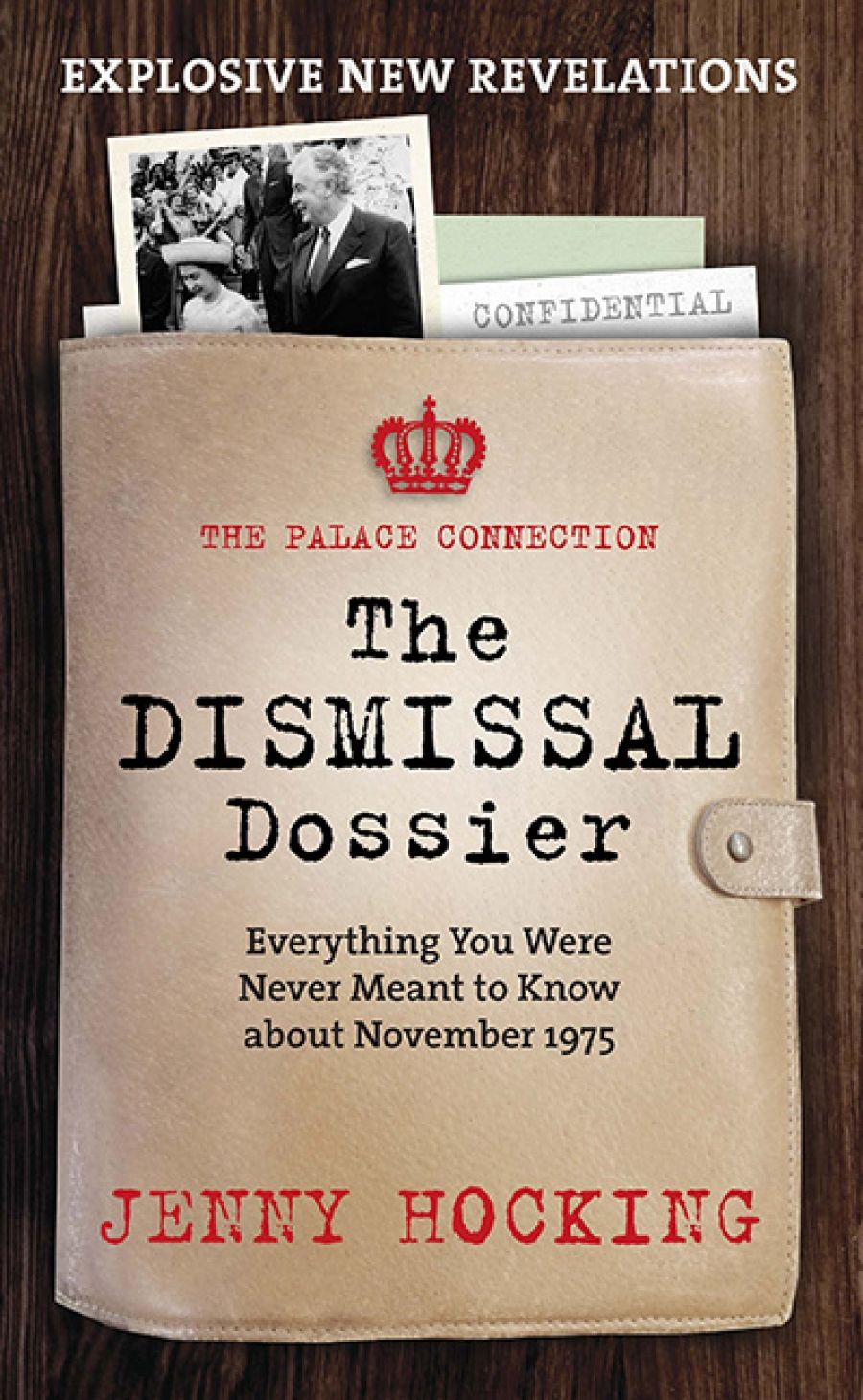

- Custom Article Title: Frank Bongiorno reviews 'The Dismissal Dossier: Everything you were never meant to know about November 1975' by Jenny Hocking

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Paul Keating claims that he wanted to arrest John Kerr. There were perhaps two points at which Kerr might justly have been taken into custody. There was the critical moment just after he handed Gough Whitlam the letter sacking him. Margaret Whitlam wondered why her husband had not simply slapped Kerr across the face ...

- Book 1 Title: The Dismissal Dossier

- Book 1 Subtitle: Everything you were never meant to know about November 1975

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $19.99 pb, 301 pp, 9780522873009

Hocking has funded the case via crowdsourcing, also securing the pro bono services of Whitlam’s son, Anthony, a QC. We are still awaiting the judgment, but even on the incomplete evidence available any idea that the British government and the queen had nothing to do with the crisis has become unsustainable. Kerr received a hint from Prince Charles and later, firmer advice from the queen’s private secretary, that in the event of a rush to the Palace, Her Majesty would probably hold things up. Kerr would therefore get in first. This exposes the governor-general as either paranoid or a liar, since Kerr claimed to have feared that Whitlam would sack him before he could dismiss the prime minister.

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office was also apparently prepared to contemplate direct interference in Australian domestic affairs over Whitlam’s ill-fated proposal for a half-Senate election to resolve the deadlock. Some FCO officials managed to convince themselves that they were justified in acting to prevent the queen from being drawn into a colonial bunfight between Whitlam and conservative premiers threatening to stop a half-Senate election by refusing to issue writs.

The dismissal was a conspiracy, in the sense that it was the result of secret plotting between several actors – most importantly Kerr and Fraser – behind the prime minister’s back, with the aim of bringing down an elected government. In a less peaceful political culture than Australia’s, failure and exposure would have placed the liberty or lives of both Kerr and Fraser, as well as several others, in jeopardy. But Australia isn’t Turkey: everyone involved well understood that Whitlam would act with the restraint customary in the leader of a constitutional democracy, even if Kerr couldn’t later forbear from lying that Whitlam had hinted that he would do otherwise.

John Kerr, former Governor-General of Australia (Wikimedia Commons)

John Kerr, former Governor-General of Australia (Wikimedia Commons)

If proprieties had been observed, Kerr would have acted on the advice of his prime minister, and not shopped around to find backing for an act he was increasingly inclined to undertake. Kerr was determined to find authorities behind whose opinion he could hide, even attending regular seminars with senior legal academics arranged for his benefit at the Australian National University. The professor of law, Geoffrey Sawer, eventually called them off, rightly worried that the university might be embarrassed by its free tutoring of the former chief justice of New South Wales if matters became too hot.

Both Fraser and Kerr lied about it afterwards, but the evidence of prior contact and agreement between them is conclusive. Fraser, an unerring judge of Kerr’s weakness, persuaded the governor-general that unless he did his duty as Fraser saw it, he might find himself in legal trouble for his formal involvement in the government’s unorthodox efforts at raising overseas loans. Hocking slightly reduces Barwick’s significance, since he only came into the picture late, but another High Court judge, Anthony Mason, was advising Kerr much earlier and nearly to the end. It is impossible to imagine his appointment as chief justice by a later Labor government if Kerr and Barwick had not covered up his involvement in the dismissal. There lies an interesting counterfactual for judicial historians.

Could this happen again? I don’t doubt that within the conservative parties today there are plenty of parliamentarians who would block supply to a Labor government if they had the Senate numbers and thought they could get away with it. What is harder to imagine is a governor-general as cowardly, crooked, and contemptible as Kerr. It is fitting that the book ends with an account of his efforts to avoid paying tax on the windfall he expected from publishing his memoirs. His alias in this matter was ‘Mr King’.

Comments powered by CComment