- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

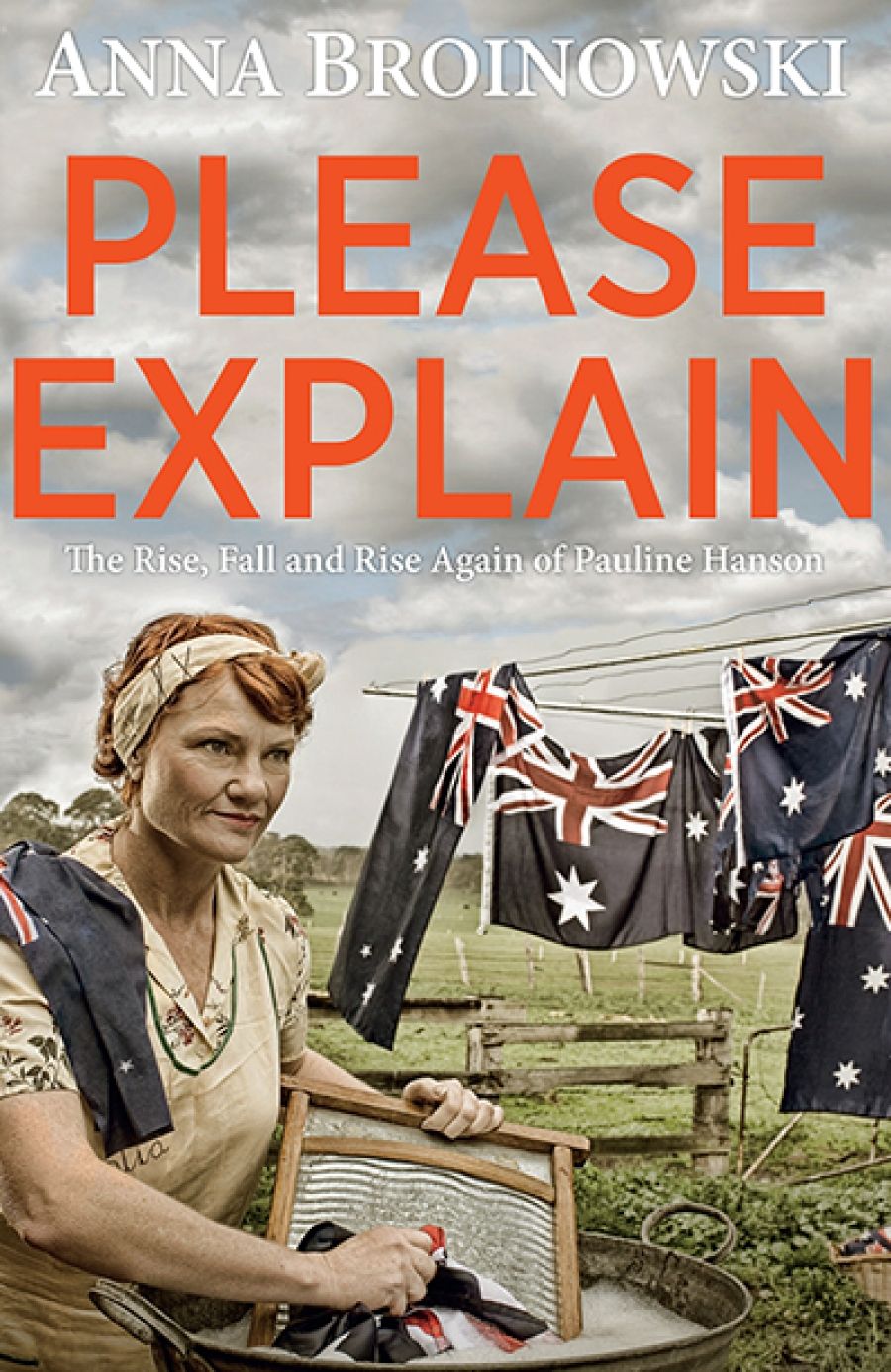

- Custom Article Title: Shaun Crowe reviews 'Please Explain: The rise, fall and rise again of Pauline Hanson' by Anna Broinowksi and 'Rogue Nation: Dispatches from Australia’s populist uprisings and outsider politics' by Royce Kurmelovs

- Custom Highlight Text:

More than any other political party in Australia, One Nation represents a puzzle for commentators. When trying to explain its support – which has hovered around ten per cent since its revival in 2016 – the temptation is to look for subtext, something deeper, beneath the surface. Could the party’s cultural pitch really be a code for ...

- Book 1 Title: Please Explain

- Book 1 Subtitle: The rise, fall and rise again of Pauline Hanson

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $34.99 pb, 312 pp, 9780143784678

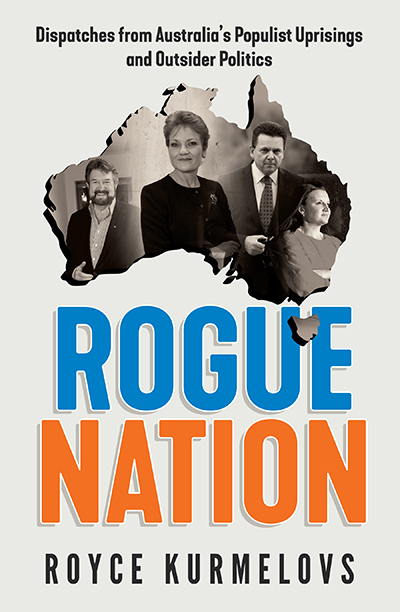

- Book 2 Title: Rogue Nation

- Book 2 Subtitle: Dispatches from Australia’s populist uprisings and outsider politics

- Book 2 Biblio: Hachette, $32.99 pb, 272 pp, 9780733639241

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Online_2017/December_2017/Rogue%20Nation_400.jpg

In the United States, this search has become an academic discipline in itself. Writers and journalists, often from big liberal cities, have set out to understand their fellow Trump-voting Americans. A kind of small-town anthropology, these works tie together various trends in modern life: the country’s ongoing heritage of racial tension; its amplification by demographic change and immigration; the slow erosion of industrial communities; and the radicalising force of partisan media. In most interpretations, these elements combined to produce the nuclear explosion that was Donald Trump’s election as president.

In the same spirit, a small but significant number of books have now been written in an attempt to understand One Nation’s resurgence in Australia. And while comparisons between Trump and Pauline Hanson should be cautious – one received sixty-three million votes and commands history’s greatest military force, the other elected four Senators – these works grapple with similar questions and a similar historical moment. As in the United States and other democracies, why is the anti-immigrant right gaining ground, and why now?

In Please Explain: The rise, fall and rise again of Pauline Hanson (2017), documentary filmmaker Anna Broinowski trailed the party’s leader during her ‘Fed Up Tour’ of Australia, in the long run-up to the 2016 federal election. Propelled around the country in a two-seater airplane, Hanson granted Broinowski broad access to the campaign. The author attended political rallies, observed Hanson’s interaction with voters, drank with her, and even received a tour of her well-manicured country property.

While slightly less Gonzo in style – Broinowski is present in the narrative, but leaves Hanson firmly in the foreground – the book’s most obvious comparison is Off the Rails (1999), Margo Kingston’s madcap diary of One Nation’s 1998 election campaign. Like Kingston, Broinowski opposes Hanson’s politics but is curious about her life, searching for any complexity and nuance behind her story. Along the way, the book gives us a gradual but clear insight into Hanson’s motivations and world view.

Though the book is fascinated by the theatre of politics – Hanson is allegedly ‘magnetic’ in the flesh, with an artist’s feel for rural campaigning – it nonetheless reveals a deeply ideological woman. This can sometimes be obscured by Hanson’s fish-and-chip-shop aesthetic, but it’s central to her politics and appeal. The emotional basis of this philosophy is hinted at early on, when Hanson scolds a young journalist:

I’m a good way through my life. It’s you guys, you’re the younger generation and you need to start taking a real interest and listen to the older generations what this country was once like, because you don’t have the same opportunities and freedoms we had. You may have the gadgets and knowledge, but you’ve lost so much, to what it used to be.

In The Shipwrecked Mind (2016), Mark Lilla describes the reactionary imagination as feeling ‘shipwrecked in the rapidly changing present, suffering from nostalgia for an idealized past, and with an apocalyptic fear that history is rushing toward catastrophe’. Hanson feels all these things deeply, and the book does a good job of tracing the beliefs backwards – to her Brisbane childhood in the 1960s, a time when communities remained homogenous, doors stayed unlocked, and families sustained themselves without government help.

While this might look like empty nostalgia – a longing for a world that never was – it expresses itself as an opposition to material and social changes in the world. When One Nation supporters say they’re ‘fed up’ with politicians, they are not really talking about the stupidity of Question Time or the entitlement of staffers – they are referring to the genuine transformations politicians have overseen.

Hanson’s vision of post-1960s Australia is indeed apocalyptic. In her mind, it has been a time of fractured communities, with a lost unity around British culture; of disorienting changes to gender and sex, with fluidity and identity trumping biology; of an increasingly aggressive Islam eroding the unspoken bedrock of Christianity; of a retreating industrial sphere, with opaque services replacing material production; and of a failed multiculturalism, with ethnic groups challenging the established centre. It is a dizzy world in which chaos has replaced order, and One Nation voters don’t like it.

There is, of course, another side to this coin. While Broinowski is generous to One Nation supporters – they are ‘embattled’ and ‘underprivileged’, trodden on by neoliberalism, while their critics are ‘élite’, ‘urban’ and ‘educated’ – she is also fair. Interviewing many of the party’s targets, from Indigenous activists to Asian community leaders, we get a sense of how painful these debates are. For every moment of cultural loss felt by One Nation voters, there is a corresponding moment of exclusion and fear felt by non-white Australians – and one stings a lot more than the other.

Pauline Hanson (Wikimedia Commons)

Pauline Hanson (Wikimedia Commons)

As Broinowski acknowledges, the reasons behind this anger at modern Australia are simultaneously simple and complex. These are also explored in Royce Kurmelovs’s new book, Rogue Nation: Dispatches from Australia’s populist uprisings and outsider politics (2017). An independent journalist from Adelaide’s industrial north, Kurmelovs previously wrote about the area’s dying car industry, before becoming Nick Xenophon’s media adviser for six months. Rogue Nation straddles these two worlds, between the polished halls of parliament and a struggling economic periphery.

The author’s short time in Canberra produced a cynicism towards politics, at least in its formal guise, but also exposed him to a broad group of federal independents and minor party politicians. In twenty-three short chapters, Rogue Nation interviews nearly all of them. It presents these figures – each squeezing their way through the widening cracks of Australia’s party system – as part of a single moment, ‘a snapshot of a time when the rules of the game seemed to be changing’.

Across the chapters, the book draws a line between political degradation, public disillusionment, and support for ‘populists’. Most of the politicians mention this feeling in their interviews, citing it as motivation for their candidacy. Kurmelovs is a crisp writer, and he links these trends to his experience in Parliament House well. In his telling, employment in federal politics is deadening and claustrophobic; a place where well-meaning people mingle with sociopaths, and where good intentions are slowly strangled.

This analysis is compelling, but there are limits to it. ‘Populism’ can be a baggy term, particularly when used to explain such diverse figures. It can also emphasise style over substance. While politicians like Jacqui Lambie, Nick Xenophon, and Ricky Muir might fit the bill – defining themselves in opposition to the composition, approach, and culture of major parties – One Nation’s critique is primarily about content. If her supporters claim that Hanson ‘tells it like it is’, it’s because they agree with what she is saying, not the way in which she is saying it.

Like Broinowski, Kurmelovs is eager to go beyond parliament, engaging with politics ‘out there’. In conversations from Tasmania to northern Queensland, the book talks to people flirting with One Nation votes. It is a grim picture, with declining industries, dwindling populations, and a deep sense of alienation. According to Kurmelovs, these people see One Nation as a ‘bull in a china shop’, there mainly to ‘make the bastards squirm’. Immigration, in this view, is a secondary concern.

Voting is complex, and social contexts shape ideas in many different ways, but this analysis can put too much faith in anecdote. As David Marr outlined in his Quarterly Essay The White Queen (2017), One Nation voters were united far more by policy preferences than wealth, according to Australian Electoral Study data. While they did tend to possess less formal education – itself a form of class – and while the party’s voters expressed anxiety about their economic futures, their defining trait was an opposition to immigration and discomfort with Islam, not any particular income level. Both books could have been more critical of this popular trope.

Regardless, Broinowski and Kurmelovs have both produced insightful, energetic books. Their desire to get their hands dirty – observing politics across a big, imperfect country – invigorates the material, and is a welcome development in Australian political writing. With One Nation’s polling holding its ground, and with the party’s drums beating loudly for the upcoming Queensland election, they should both remain relevant for a good time to come.

Comments powered by CComment