- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Christopher Menz reviews 'Rayner Hoff: The life of a sculptor' by Deborah Beck

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Rayner Hoff, the most significant sculptor to work in Australia between the wars, is most admired for his sculptures in the Anzac war memorials in Sydney and Adelaide. His work was in the classical figurative tradition in which he had trained. While never part of the international avant-garde, he remained modern for ...

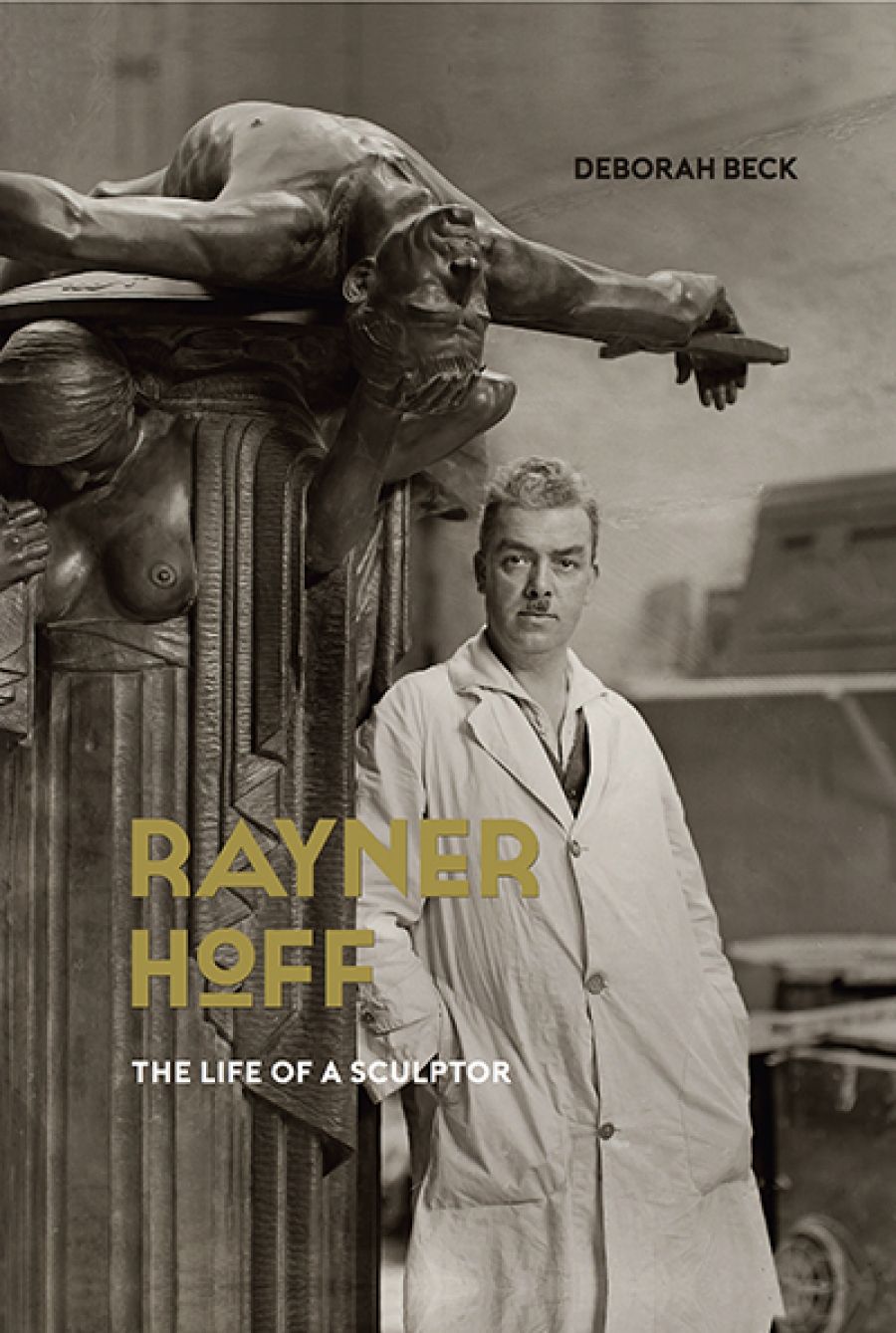

- Book 1 Title: Rayner Hoff

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of a sculptor

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $49.99 pb, 280 pp, 9781742235325

The story of how this Manx sculptor became such a significant figure in the interwar Australian art scene makes fascinating reading. Rayner Hoff was born in 1894. In 1902 his family left the Isle of Man for the mainland, lured by better work opportunities for his stonemason father. Hoff was himself apprenticed as a stonemason in 1908 at Wollaton Hall, an Elizabethan Robert Smythson prodigy house near Nottingham. From his earliest training he was exposed to the powerful expressive quality that an admixture of sculpture and architecture can have. From the age of fifteen he also studied at the Nottingham School of Art, where he was a successful student. After war service, Hoff continued his studies at the Royal College of Art in London; his fellow students included Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. He graduated in 1922 and won a scholarship which took him to Rome for several months. Fortunately for Australia, while he was there he accepted a position as a teacher of Antique and Life Drawing, Modelling, Architectural Modelling and Sculpture at the Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School). Like many artists before and since, Hoff had had to choose between paid work and further studies. That the teaching position on the other side of the world paid nearly three times his scholarship fee must have been an incentive.

Hoff arrived in Sydney with his wife and infant daughter in 1923 and relished his new role. As a teacher he had great success at the school; he was much admired, and his demanding methods produced fine students. Hoff was actively involved in the Sydney art scene and gained many prominent commissions. His early death from pancreatitis in 1937 at the age of forty-two robbed Australia of an artist at his peak.

Hoff’s masterpiece, completed in 1934, is the sculpture components of the Anzac Memorial, Hyde Park, Sydney, produced in collaboration with architect C. Bruce Dellit. The most notable part of the ensemble is the centrepiece sculpture Sacrifice, Australia’s finest and most moving memorial to the Great War. In a classical idiom, with a column of women supporting a nude male figure, the sculpture combines images that represent the sacrifices of both men and women. Sadly, not all of Hoff’s sculptures for the Anzac Memorial were completed. Australian wowserism, so averse to the depiction of female nudity, deprived it of two proposed bronze external sculptures: the nail in the coffin was from the Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney. As keepers of public morals, the church used expressions such as ‘gravely offensive to ordinary Christian decency’ and even resorted to invoking its traditional adversary, describing the sculptures as ‘diabolic’.

ANZAC War Memorial, Hyde Park, Sydney, Australia (photograph by Adam.J.W.C, Wikimedia Commons)

ANZAC War Memorial, Hyde Park, Sydney, Australia (photograph by Adam.J.W.C, Wikimedia Commons)

Hoff’s interaction with other artists is explored in some detail. There is a fine account of his friendship with Mary Gilmore, which arose when she sat for the bronze portrait, Gilmore (1934), now in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Gilmore wrote: ‘Under the skin the flesh, under the flesh the bone, and behind the bone the ancestor. When I think of what you have done for this sad tired ugly face and the circumstances under which it was done I am filled with wonder.’ Through his friendship with Norman Lindsay, we learn about Hoff’s attitude to Rodin’s work: ‘he failed to fuck his own creations, and wasted cock-stands on women instead of work.’

Rayner Hoff's sculpture Sacrifice inside the ANZAC War Memorial, Hyde Park, Sydney (photograph by Greg O'Beirne, Wikimedia Commons)

Rayner Hoff's sculpture Sacrifice inside the ANZAC War Memorial, Hyde Park, Sydney (photograph by Greg O'Beirne, Wikimedia Commons)

This splendid volume is generously illustrated with a marvellous selection of photographs that, along with the text and selected quotes from contemporaries, through their letters, gives a vivid sense of Hoff’s generous personality and broad interests. Without a vast archive of primary text-based sources by the subject to draw on, Deborah Beck has used photographs as a starting point for her discussion of Hoff’s life and work. The story is plainly and engagingly told. Beck, who is archivist and collections manager at the National Art School, gives a rich contextual background to the art schools where Hoff trained and worked. There is much insight into the art scene in Sydney during the 1920s and 1930s; from this distance it seems so intimate and small. Beck’s account gives fascinating detail on the commissions, the production methods, the roles of models, the relationship between sculpture and more commercial design work, and the collaborative nature of large sculpture projects, notably the Anzac Memorial.

Comments powered by CComment