- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

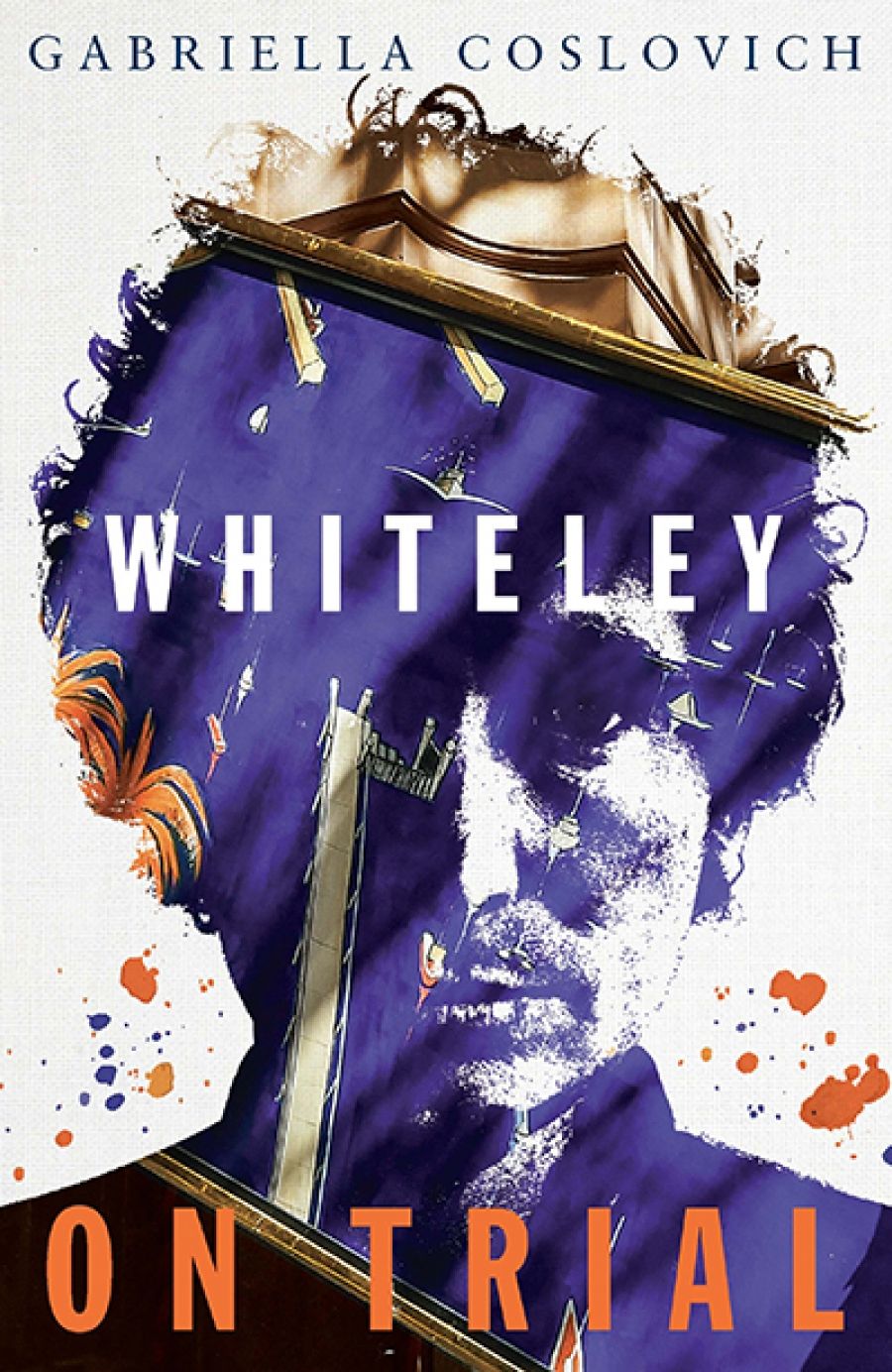

- Custom Article Title: Johanna Leggatt reviews 'Whiteley on Trial' by Gabriella Coslovich

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It was the late Robert Hughes who said that ‘apart from drugs, art is the biggest unregulated market in the world’. Journalist Gabriella Coslovich quotes him in her account of the 2016 Whiteley art fraud trial, repeating the line to one of the accused, art dealer Peter Stanley Gant, as he complains to Coslovich about the ramping ...

- Book 1 Title: Whiteley on Trial

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $32.99 pb, 360 pp, 9780522869231

The case was highly unusual on a number of fronts. Whistleblower Guy Morel, who was not a victim of the alleged fraud, had come across the suspect paintings at Siddique’s Collingwood storeroom. Between 2007 and 2010 he secretly photographed the creation of three large paintings in the style of Whiteley. Gant maintains he sourced the paintings in 1988 from Whiteley’s assistant at the time, Christian Quintas, who died before charges were laid. The prosecution alleged that Siddique was creating the suspect paintings in an arrangement with Gant, who would then sell them as Whiteley originals. The defence, in turn, alleged the paintings in the storeroom were mere copies. It is not illegal, after all, to attempt to copy an artist’s work. Whiteley’s ex-wife, Wendy, who was estranged from her husband during the period he supposedly painted the works, emphatically maintained that they were fakes. The defence argued that she couldn’t possibly comment with any authority.

Disputes over the provenance of paintings and their authenticity are rarely decided in Australia’s criminal courts and, tellingly, none of the alleged victims pressed charges, despite rumours circulating in the media since 2010 about the suspect paintings. Many factors combine to keep art fraud cases out of the Australian criminal jurisdiction. They are notoriously hard to prosecute, as police often don’t have the resources to devote to them – the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission has shown little interest in tracking down art fakes – and victims are frequently reluctant to speak out because they either feel foolish or fear the devaluation of their investment. The first alleged victim, Sydney luxury car dealer Steven Nasteski, dropped the police matter after the $1.1 million he spent on the suspect Orange Lavender Bay, was returned, while investment banker and Sydney Swans chairman, Andrew Pridham, sought the $2.5 million he spent on the suspect Big Blue Lavender Bay in the civil courts by filing a suit against Anita Archer, the art consultant who had sold him the piece.

Coslovich includes an extensive account of the seven-day committal hearing. This would be excessive if she were writing about almost any other case, but, considering the complicated nature of the charges, the inclusion of both committal and trial evidence is illuminating. The evidence presented, after all, differs depending on the court of law. At committal, the defence questioned the accuracy of solvency tests on the paintings, and, as a result, these tests were omitted entirely from the prosecution’s evidence at trial. Furthermore, Coslovich writes that, at the committal, photographer Jeremy James wasn’t 100 per cent sure whether the contentious art catalogue from 1989, allegedly referencing the suspect Orange Lavender Bay and Big Blue Lavender Bay, had even been published. By the trial he was unequivocal: twenty had been printed.

The alleged forgery Big Blue Lavender Bay (photograph by Kate Ballis)

The alleged forgery Big Blue Lavender Bay (photograph by Kate Ballis)

The notion of connoisseurship and its place in a court of law is one of the many interesting ideas teased out in the book. During the committal, defence barrister Robert Richter QC rails at the evidence of the witnesses brought in to testify that the paintings were fake, depicting their attempts at verification as little more than wishy-washy postulation with scant scientific basis. Throughout the trial, the defence team continues the line, arguing that the prosecution had fallen prey to the ‘masterpiece syndrome’ and that not everything Whiteley painted was masterful.

Barry Pearce, former head curator of Australian art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, is wonderful on the topic of what makes a Whiteley a Whiteley – the dash and energy to the paintings, the exquisite lines, the subtle shifts in texture, the momentous pace of them. A fake, he tells Coslovich, doesn’t give you ‘that hit, that buzz’. ‘The trouble is,’ Pearce says, ‘If you get up in a court and start saying this, these vicious barristers will say, “What’s this crap you’re talking about?” They’ll say it’s some esoteric language. I would refuse to go into court because it is so traumatic when you get attacked by the barristers.’

The best works of non-fiction are those in which the author is possessed in some way by her line of enquiry. In Coslovich’s case, her interest appears to be more than just an extension of her run as arts writer at The Age. She doggedly follows leads, conducts her own research into the provenance of the paintings, and, at times, seems more across the facts than the courtroom barristers. Coslovich and Gant go back years; in 2011 he sued The Age over a series of stories she wrote. And yet he agreed to be interviewed by her on more than one occasion. Her background in journalism is a boon for the reader: she is impressively dedicated to pursuing the major players for interviews. But two key figures, Siddique and Pridham, refuse to speak to her. Coslovich’s first-person account of the case largely works, but she waits until the end of the book to detail previous Australian art fraud cases, from the outset denying the reader important contextual information as to where the trial sits in the history of Australian art fraud convictions.

Peter Gant and his daughters rejoicing after his acquittal on 27 April 2017 (photograph by Justin Mcmanus, Fairfax Syndication)

Peter Gant and his daughters rejoicing after his acquittal on 27 April 2017 (photograph by Justin Mcmanus, Fairfax Syndication)

Coslovich is a seasoned arts journalist, but, by her own admission, an inexperienced court reporter. She struggles with the burden of proof resting with the prosecution, and suggests that certain defence evidence may be further proof of the pair’s guilt. If you are going to fake a painting, she reasons, you are going to fake provenance, so it is little surprise that certain facts seem to line up neatly. This may well be true, but it is irrelevant when the prosecution’s requirement is to prove beyond reasonable doubt a case of circumstantial evidence.

When placing the case within a broader context, Coslovich is acutely aware of what the failed fraud trial means for future prosecution attempts of alleged art fraud. She notes that the art and legal worlds remain as separate as ever, and that the case has not resulted in a greater accommodation for the role of the connoisseur in the courtroom, for the expert who relies not on blood traces and fingerprints but on stylistic patterns of recognition. Ten years after police investigations began, a shadow still lingers over the suspect Whiteley works, their provenance uncertain as ever.

Comments powered by CComment