- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

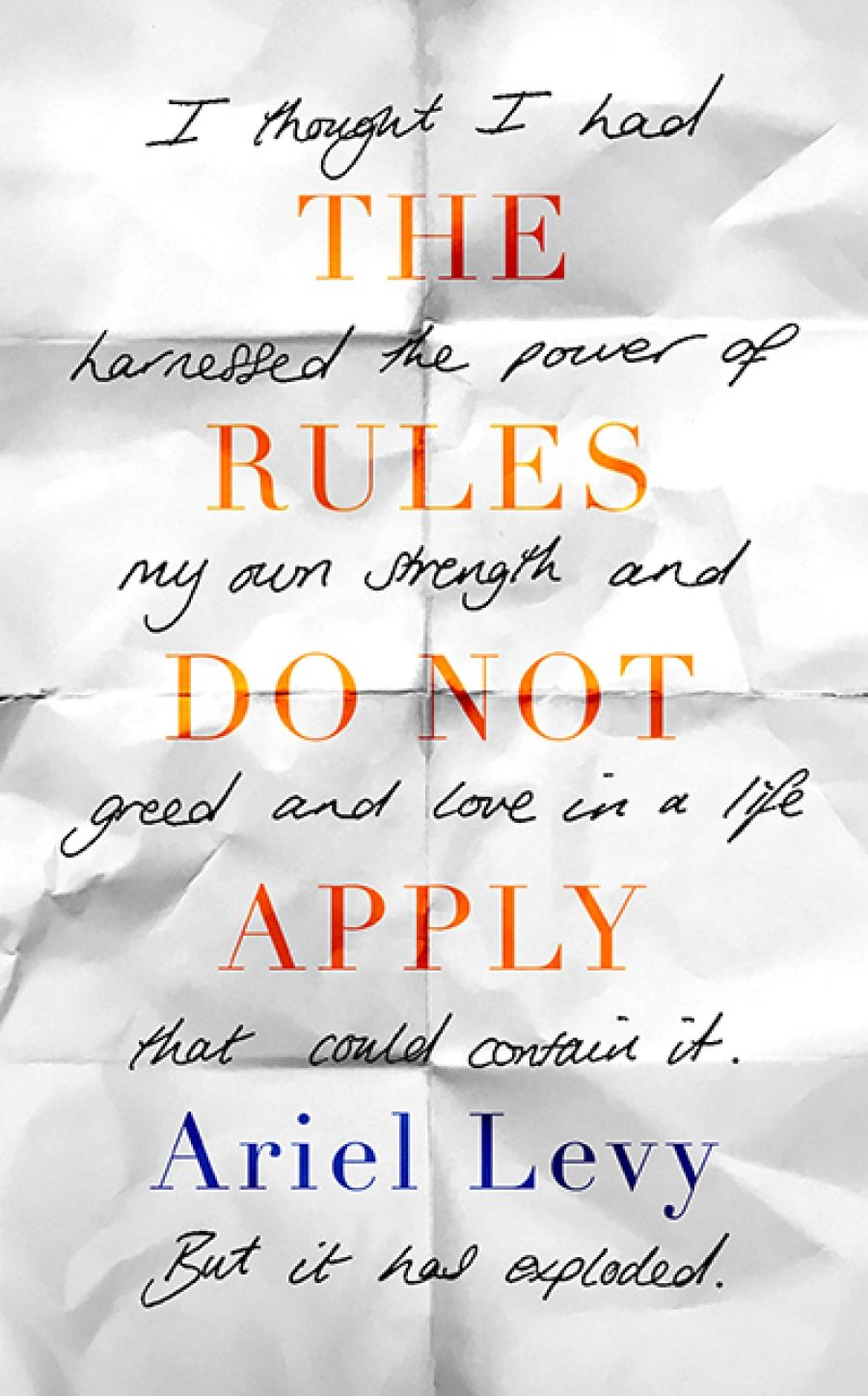

- Custom Article Title: Carol Middleton reviews 'The Rules Do Not Apply: A memoir' by Ariel Levy

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the first chapter of her memoir, The Rules Do Not Apply, Ariel Levy writes, ‘Daring to think that the rules do not apply is the mark of a visionary. It’s also a symptom of narcissism.’ Born in New York during the Reagan era, she is describing the world she grew up in, one in which you were told that you were in control of your ...

- Book 1 Title: The Rules Do Not Apply

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $29.99 pb, 208 pp, 978034900530

The bathroom scene became the kernel of the memoir, which explores what came before and after the baby’s birth. Levy goes back to her childhood, to find the place where her path began. Her father played a game with her, Mummy and the Explorer, in which she chose to play the Explorer, a role she has kept up ever since, taking risks and thrusting her way around the world in pursuit of adventure and controversial stories. At an early age she decided to become a writer. This meant ‘paying her dues’ as an assistant at New York magazine in the 1990s, but she was on the road to freedom.

The idea for her first major assignment, about an obese women’s nightclub, was given the nod by the editor of New York magazine, John Homans: ‘That’ll be fun for you, Miss Ari.’ That essay also went on to become her first book. Female Chauvinist Pigs (2005) is a polemic against the raunch culture that women were embracing in the belief that it was empowering and feminist.

Gender issues and sexuality have been constant themes in Levy’s journalism, and they inform The Rules Do Not Apply. Levy examines her own sexual development, her joy in finding fulfilment with a woman, Lucy, and embarking on pregnancy in her late thirties. With clear-sighted honesty, she admits to the blindness that prevented her from acknowledging Lucy’s alcoholism and questions her own behaviour: ‘You don’t fly to Mongolia pregnant.’

Like Joan Didion, who famously said, ‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking’, Levy is on a journey of self-exploration. She begins the memoir in journalistic mode, in fine command of structure, motif, and theme. She calls her famous friends by their surnames. She has an annoying fondness for brackets. She writes at a distance from her subject, in this case herself, with a wry sense of humour. In poised, professional prose, Levy pre-empts our disapproval of her risk-taking behaviour and any charge of self-indulgence in her grief by stating upfront, ‘It’s all so over-the-top. Am I in an Italian opera? A Greek tragedy? Or is this just a weirdly grim sitcom?’

Ariel Levy (Wikimedia Commons)

Ariel Levy (Wikimedia Commons)

By the time she meets Lucy, the woman she marries (unofficially), she has left her flippancy behind and her writing has become more urgent; now she uses language to uncover the emotional reality, reveal her vulnerability and describe a world in which she is losing control. She describes her first encounter with Lucy with unabashed naïveté:

She was golden-skinned and green-eyed in her white shirt, and she smiled with all the openness in the world when I walked in the door. She had the radiant decency of a sunflower. It felt as if I had conjured her out of the dark. Not just the bewitched darkness of the blackout, but all the nights that had come before then, when I went to bars and parties, searching for someone who wasn’t there. But here she was now.

Two thirds of the way through the memoir, we come upon the scene in Mongolia, much of it lifted verbatim from the original essay. It is gut-wrenching, with a profound sense of loss. Levy’s ‘competent self’ has finally given way, taken over by her ‘bewildered self’, and she is alone. ‘Grief is another world. Like the carnal world, it is one where reason doesn’t work.’

There is a subtle shift through the memoir from this competent self, the self-made journalist, to the fearless woman who faces the exigencies of nature: life and death. It takes the loss of all she loves to realise that she is not in control: certain bodily experiences, in particular, are out of our control, and take place beyond the realm of language. Giving birth is one. Remarkably, Levy has found words to describe the visceral emotions that attend birth and death. Drawing on her skills to uncover the animal nature of her womanhood, she has made the transition from journalist to author gracefully.

Comments powered by CComment