- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Klaus Neumann reviews 'Asylum By Boat: Origins of Australia’s refugee policy' by Claire Higgins

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In early October 2017, Thomas Albrecht, the Canberra-based Regional Representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), took to The Guardian to register his dismay about the Australian government’s response to asylum seekers. ‘The current policy has been an abject failure,’ he wrote. ‘A proper ...

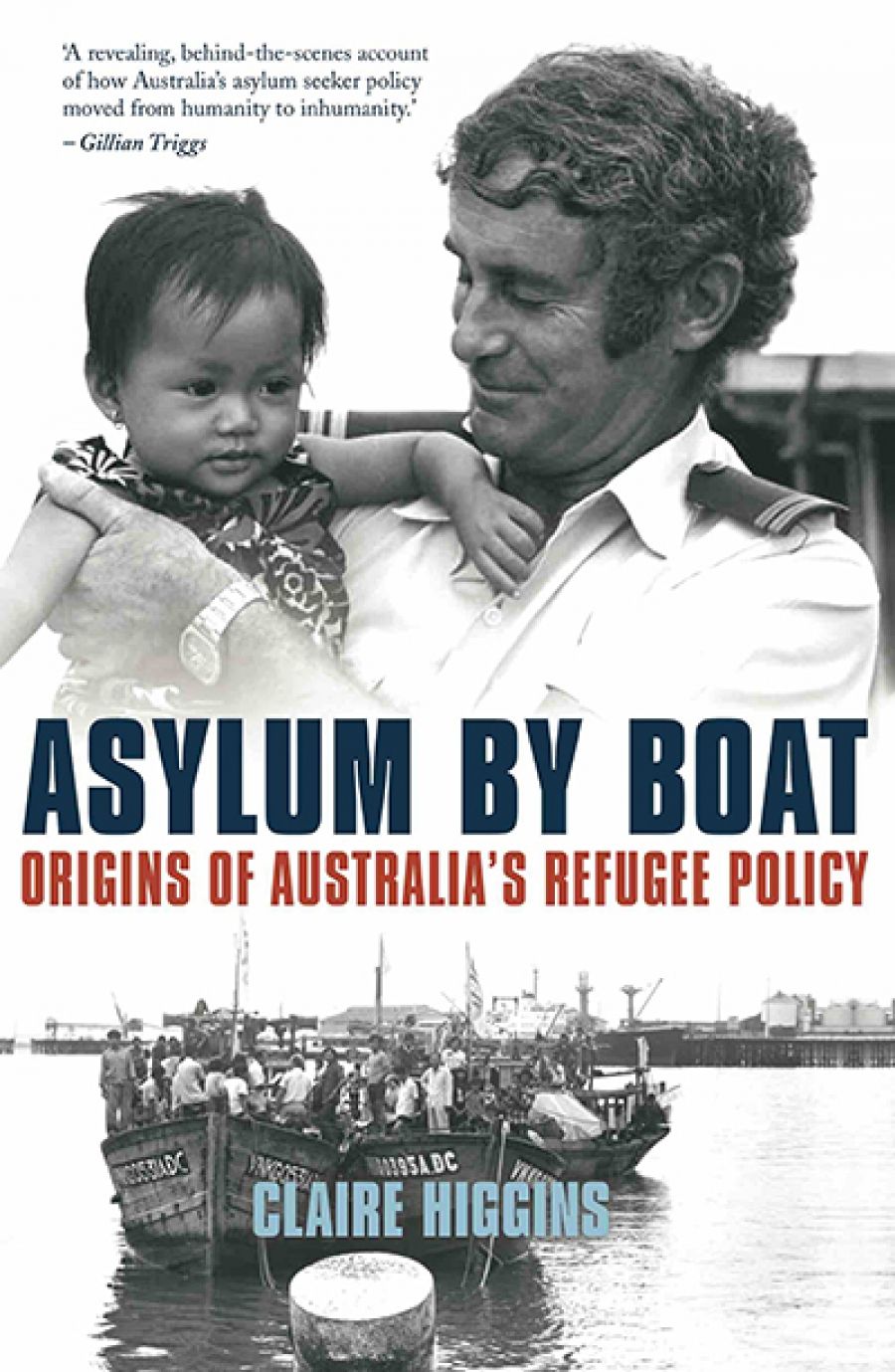

- Book 1 Title: Asylum By Boat

- Book 1 Subtitle: Origins of Australia’s refugee policy

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $29.99 pb, 250 pp, 9781742235677

Using Goodwin-Gill’s notes about the committee’s deliberations, Higgins highlights the ‘clear and unexpected differences’ among its members. For example, while the immigration department’s representatives voted in more than four out of five cases for Vietnamese boat arrivals to be accorded refugee status or to be allowed to remain in Australia on compassionate or humanitarian grounds, the Attorney-General’s Department’s delegate was in more than seventy-five per cent of cases opposed to such a course of action. What is even more remarkable is the role played by Goodwin-Gill. While his views did not always prevail, they were taken seriously. From today’s vantage point, it appears even surprising that the Fraser government invited the UNHCR to join the DORS committee in the first place. The kind of stand-off between the local UNHCR representative and the Turnbull government which prompted Thomas Albrecht to voice his concerns in The Guardian, would have been unthinkable during Goodwin-Gill’s Australian posting.

Any history of Australian responses to asylum seekers under Malcolm Fraser invites comparisons with the government’s approach under prime ministers John Howard, Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard, Tony Abbott, and Malcolm Turnbull. Higgins does not avoid contrasting past and present policies and practices. But she is careful not to let her historical analysis suffer in order to be better able to use the past as a weapon in a debate about present-day policies. That is one of the key strengths of Asylum by Boat.

In public debate, critics of today’s asylum seeker policies often hold up Fraser’s approach as exemplary. The claim that his government was able to deal with ‘boat people’ compassionately and without compromising either Australia’s international reputation or its sovereignty was made, not least, by Fraser himself. Higgins interviewed Fraser, his immigration ministers, Michael MacKellar and Ian Macphee, and other key players. It is to her credit that Asylum by Boat does not rely on their recollections, and sometimes draws attention to discrepancies between former politicians’ – sometimes self-serving – accounts and what could be gleaned from Australian government records and Goodwin-Gill’s files. The result is a nuanced account, which also shows that Fraser and his Cabinet seriously contemplated setting up detention centres for boat arrivals, and that they went to great lengths to stop Indochinese refugees from making the boat journey to Australia.

The Fraser government pursued at least four avenues to halt the flow of asylum seekers arriving by boat. It launched a substantial refugee resettlement program that targeted Indochinese refugees in camps in Southeast Asia. Eventually, they let themselves be convinced that it was better to wait to be resettled, rather than risk the perilous boat journey to Australia. Here, it should be remembered that Australia’s resettlement of Indochinese refugees began in earnest only after the Australian public became concerned about the arrival of ‘boat people’. Australia also entered into a bilateral agreement with Vietnam to facilitate family reunion; that, too, was a means that pre-empted irregular departures by prospective refugees.

The other two planks of the government’s ‘stop-the-boats’ policy were comparatively less successful. Vis-à-vis its Western allies, Australia insisted on the principle of burden-sharing; while the United States and Canada accommodated a substantial number of Indochinese refugees, Japan and most Western European nations were less willing to do so. Finally, Australia tried to convince its neighbours in Southeast Asia to discourage refugees from sailing to Australia. With Indonesia, for example, Australia negotiated an informal arrangement, which is termed the ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ in Australian government records. It committed Indonesia to prevent refugees from continuing their journey to Australia in the understanding that all of them would be resettled by Australia. Sometimes the Indonesians honoured this agreement, but on many other occasions they did not.

Higgins’s book is a meticulously researched and well-written analysis of the Fraser government’s approach towards asylum seekers arriving by boat. The problem with such a comparatively narrow focus is that relevant precedents, such as the reception and assessment of West Papuans seeking asylum in the Australian Territory of Papua and New Guinea, and the government’s overall human rights and immigration policies remain beyond the book’s purview. But Higgins points out that there is ‘a real need for further archival research and nuanced analysis’; hers is therefore unlikely to be the last history of Australia’s response to refugees in the 1970s and 1980s.

The book’s sixth and last chapter takes the story from the early 1980s to the early 1990s, and thus to the introduction of mandatory detention for asylum seekers who arrived by boat, which marked a significant break from the Fraser government’s approach. Here, the scope for more analysis – to further explain that break – is most evident. The end of the ‘bipartisan accord’ that had underpinned Australia’s migration policies, features prominently – and rightly so – in Higgins’s explanation. Historians have commonly associated the end of bipartisanship with the mid-1980s, when Geoffrey Blainey and John Howard questioned the Hawke government’s non-discriminatory immigration policy. But substantial disagreements over Australia’s response to asylum seekers already surfaced during the 1977 federal election campaign, when prominent Labor Party politicians tried to gain political mileage by demanding that boats carrying Vietnamese asylum seekers be turned around. Labor eventually supported the government’s policies, but not before introducing the term ‘queue jumper’ into the Australian political lexicon. Arguably, the anti-asylum seeker rhetoric of Bob Hawke, Gough Whitlam, and other Labor leaders laid the foundations for the ‘abject failure’ diagnosed by Thomas Albrecht.

Comments powered by CComment