- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environment

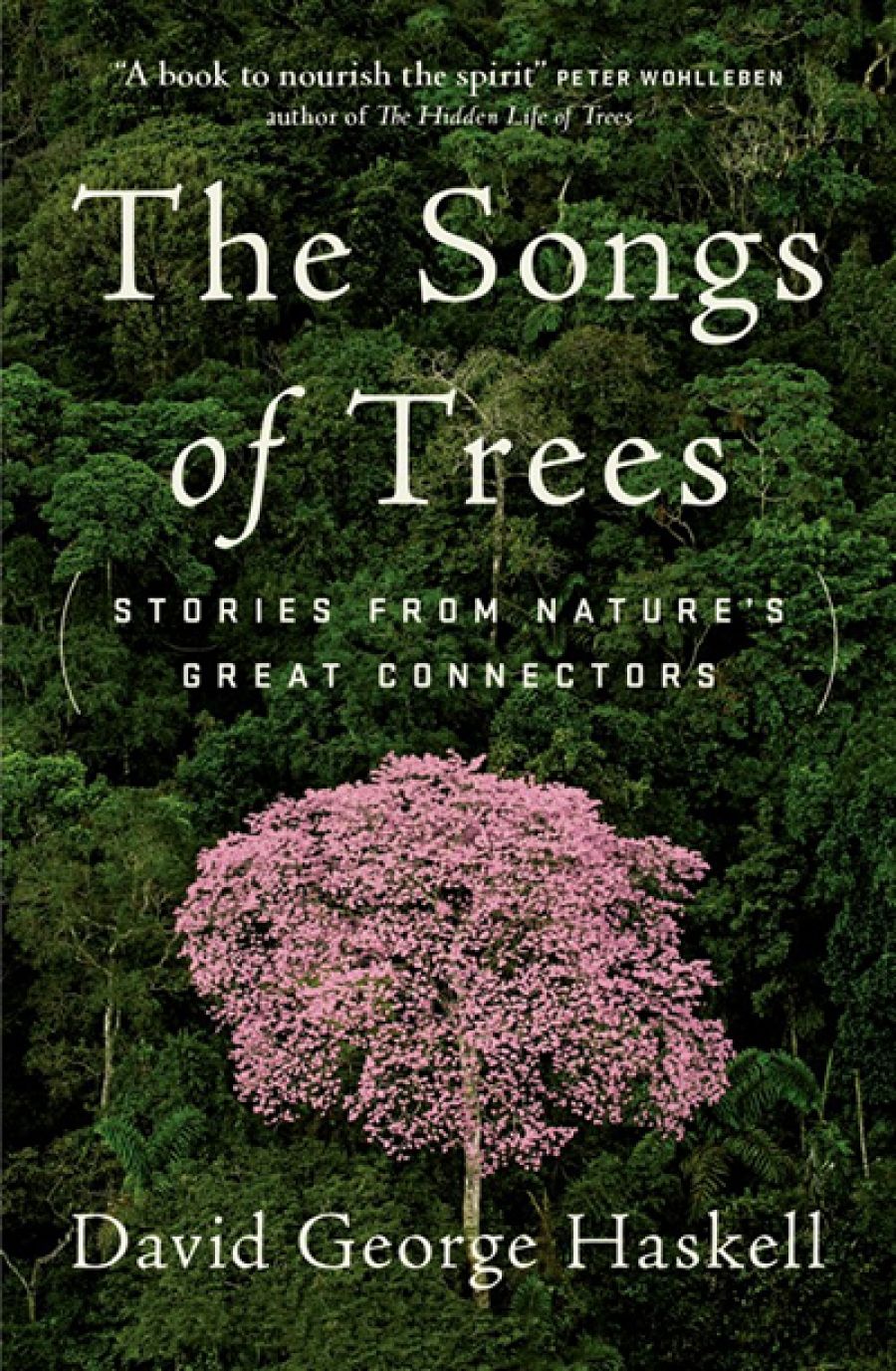

- Custom Article Title: Roger McDonald reviews 'The Songs of Trees: Stories from nature’s great connectors' by David George Haskell

- Book 1 Title: The Songs of Trees

- Book 1 Subtitle: Stories from nature’s great connectors

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.99 pb, 304 pp, 9781863959261

Haskell won’t have it like this. ‘For the Homeric Greeks, kleos, fame, was made of song. Vibrations in air contained the measure and memory of a person’s life. To listen was therefore to learn what endures.’ He attributes consciousness to trees, a cell-reaction awareness: ‘If we broaden our definition and let drop the arbitary requirement of the possession of nerves, then the balsam fir tree is a behaving and thinking creature.’

So trees really and truly might actually sing in the way people do? Haskell, we sense, smiles faintly, and gives a conditional, fudgy sort of nod, followed by a small head-shake as the poet in him gives way to the scientist, allowing him the wit to admit that ‘much of this song dwells under the acoustic surface’. Quite often, in Haskell’s writing, ‘sound’ fudges into ‘song’. The scientist hears sound. The poet wants song.

Interconnection and overlapping is Haskell’s theme as a biologist and is inherent in his voice as a writer. Sometimes that voice leaves the reader feeling a bit more editorial work could have been done separating poet and phrasemaker from the scientific explainer. The songs of trees as a linking metaphor can sound like sermonising. Haskell wants us, as readers, to hear something, not just sound, as a crucial component of ecology, but to hear a meaningful composition of sound.

In each of his twelve chapters about twelve different tree species, we see Haskell best in action, rambling through forests both paradisically untouched and wreckingly exploited in Ecuador, North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Japan. In the Ecuadorian Amazon, with layers of growth creating aerial forest floor high above ground level, he hears the rain ‘not through silent falling water but in the many translations delivered by objects that the rain encounters’. Here, in sodden humidity, ‘the forest presses its mouth to every creature and exhales’. Among bird and animal life, ‘every sonic verb has its champion’. Back at a field station he gets bitten by a bullet ant. ‘The pain was like a strike on a bell cast from the purest bronze.’ But the pain is so well-described that the reader laughs, not unsympathetically but because any really truthful description of someone put out is funny.

Trees at Börnste, Germany (photograph by Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons)

Trees at Börnste, Germany (photograph by Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons)

This personal detail modestly dramatises what Haskell calls ‘ecological aesthetics’, an awareness of our tangling up in nature’s blockages and diversions and a hope for action (Darwin’s version of the ‘tree of life’ metaphor was a ‘tangled bank’.) It goes back to the first bacteria. ‘Two billion years ago, the boundary between self and community was already blurred. The fundamental nature of life may not be atomistic but relational.’

Listening, putting his ear to the ground, cupping his ear to a tree or to the wind in a forest, is Haskell’s primary mode. Anything to do with sensation, hearing, touch expands him. We find him on hands and knees in the frozen Canadian north noting how ‘the swell of growing roots causes shards of rock to click, a sound so quiet and muffled that I detect it only with a probe nestled into rocky ground’. The scientist and no doubt inspiring university teacher cannot prove, in fact no one has yet, he says, if sounds in the underground of trees are analogous to the well-known chemical signals that travel among roots. ‘Too few human ears have attended to the soil’s chatter.’ He means there has not been enough research done. (Tim Low, author of Where Song Began [2014], has noted that ‘sound is a latecomer to bio-geographical attention’.)

By ‘chatter’ Haskell means roots ‘conversing’ with fungi. He says a ‘root chimera’ is involved, though he is ‘agnostic’ as to whether gods and goddesses are involved in natural processes. Regarding supernatural explanations, though, having coyly played with them, he swings back and roots life in biology. ‘There is life after death, but it is not eternal.’

As a science writer, Haskell reminds me of the late Loren Eiseley, aching to spiritualise matter by pushing what can’t be had through religious belief into ultra-poetic phrasing. In Haskell, a bird’s steps are ‘fox-silent’; a waterbird ‘toad-climbs’ to the shore; Bible stories ‘finger’ Palestine; an electron microscope has ‘thrumming power’; ducks ‘beak’ a shoreline; an outbreak of yellow fever is ‘sylvatic’; leaves are ‘many-skilled’.

David George HaskellIntelligence, beauty, will, and Haskell’s feeling of consciousness taunting from a tree’s chemistry weave in and out of non-human nature for him, and he wants us to feel it too. We get what he means – we, as a species, must ‘unself’ ourselves into nature – although professional philosophers playing with natural history as a current trend might get cranky with him for locating intelligence outside consciousness.

David George HaskellIntelligence, beauty, will, and Haskell’s feeling of consciousness taunting from a tree’s chemistry weave in and out of non-human nature for him, and he wants us to feel it too. We get what he means – we, as a species, must ‘unself’ ourselves into nature – although professional philosophers playing with natural history as a current trend might get cranky with him for locating intelligence outside consciousness.

Like his observer–experiencer–compatriot Thoreau, Haskell, with his students, gathers and lists everything washed up on a US Atlantic shoreline. Everything Thoreau found (including a corpse) would ultimately decay. Haskell and his students found nothing but plastic. You sense him going back to the field station and being inspiring to young minds, then anti-romantic, possibly self-rebuking, after a run of epiphanies: ‘Ecological beauty is not titillating prettiness or sensory novelty. An understanding of life’s processes often subverts these superficial impressions. Ecological aesthetics is not a retreat into an imagined wilderness where humans have no place but a step toward belonging in all dimensions.’

The sound of trees has stupendous richness that Haskell thoroughly explores. He refers to Robert Frost’s poem ‘The Sound of Trees’ (1916), whose lines somehow encapsulate his theme:

I wonder about the trees.

Why do we wish to bear

Forever the noise of these

More than another noise

So close to our dwelling place?

Comments powered by CComment