- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Brian Matthews reviews 'A Führer for a Father: The Domestic Face of Colonialism' by Jim Davidson

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: A Führer for a Father

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Domestic Face of Colonialism

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $29.99 pb, 264 pp, 9781742235462

There is a photo – inaccessible to me now – of my father (with Hitler moustache) gravely advancing towards the camera. He has just stepped off Princes Bridge, so part of the city of Melbourne is ranged behind him; he always drew on it more than he cared to admit. In his right hand there’s a walking stick, with a silver top: it had been given to his grandfather by a prominent Chinese merchant of the town. Father’s firm grip indicates a governing principle of his life, the control of the exotic. Functionally, the stick would turn a limp after a motor accident into a stylised, emphatic strut. It became an instrument of authority.

Given its brevity, this is extraordinarily proleptic. The strut; the ‘swagger stick’ (as it was known in the Australian army) with its ornate top; the hint of pre-eminence (the city ‘ranged’ behind him); the posturing; the authoritarianism; the penchant for exoticism and adventurous travel – all these and much else will emerge graphically as the memoir gathers pace and detail. And the import of the initially rather gnomic subtitle – ‘The domestic face of colonialism’ – is also gradually revealed: the father establishes an ‘imperial dominance’ based on patriarchy; he seeks moral control over the family and its various outliers; like a colonising intruder he dominates and manipulates social relations and aspirations and attempts to exploit people economically. Davidson père is a monster – a narcissist, a pathological controller, in short a führer.

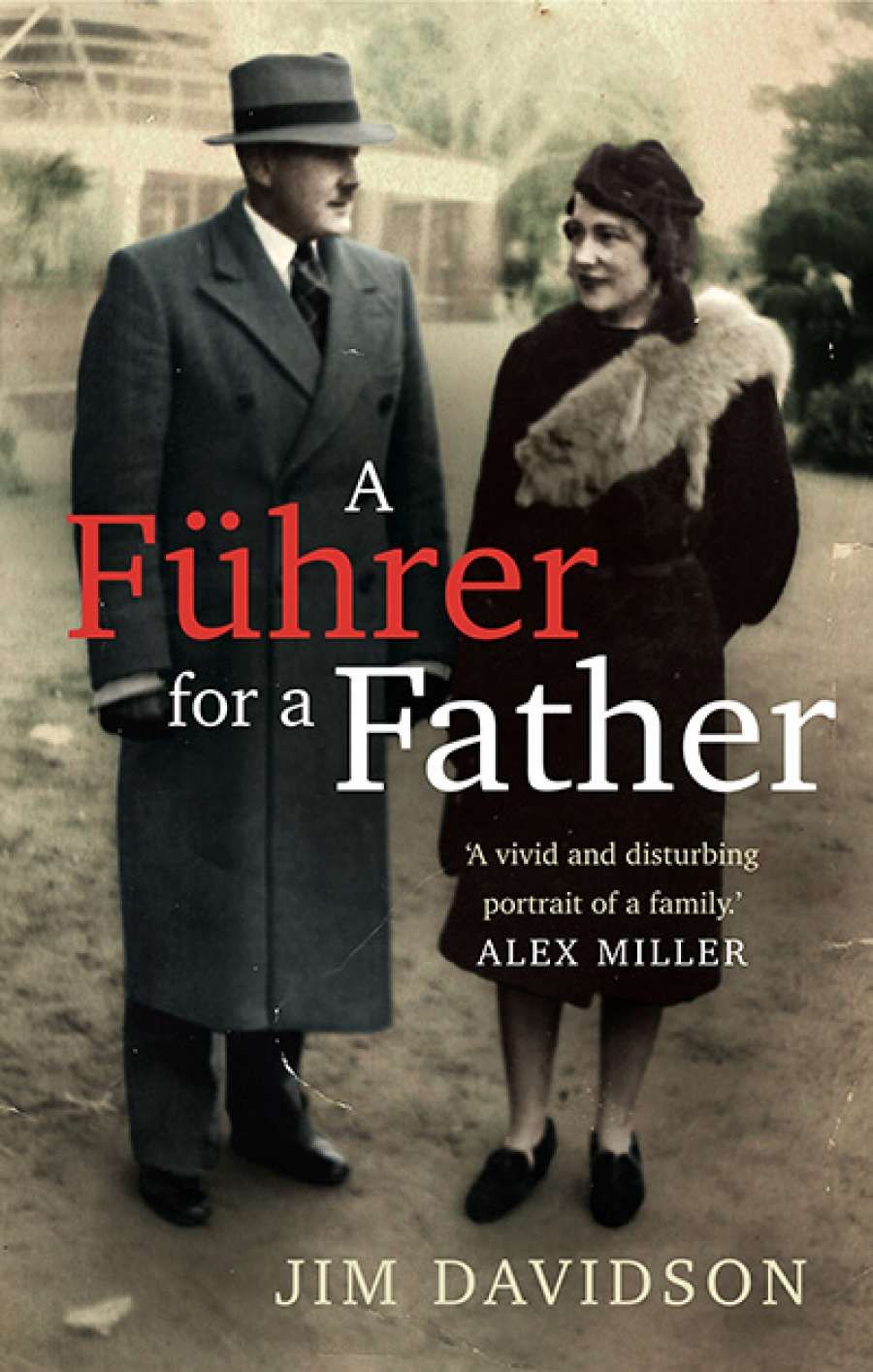

A description of a formal photo of his parents not long married, taken, as many such photos were, at the Zoo, captures the sense of something at odds here, of vague yet nagging disquiet. His father is ‘almost elegant, standing in a fine coat with hands held by his side, plus his Hitler moustache ... he looks at Olga commandingly ... Olga returns the gaze, warily. Her smile is checked, and not just by the camera. The Zoo, with its exotic contents, would have appealed to Jim as a suitable backdrop. But Olga was beginning to feel captive herself.’

Jim Davidson as a baby, with his mother, Olga (image courtesy of Jim Davidson)The other important strand in Davidson’s narrative is of course his own memoir: it will be intermittently darkened, burdened, interrupted, and temporarily destabilised by the powerful intrusions of his colonising and often ruthless father, though it has its lighter moments. There are many successes and achievements, and there is his moving compassion for his mother who is no match, in all senses of that word, for the man she married and whom Davidson is above all concerned to re-establish in the family story – his own quiet version of the empire writes back.

Jim Davidson as a baby, with his mother, Olga (image courtesy of Jim Davidson)The other important strand in Davidson’s narrative is of course his own memoir: it will be intermittently darkened, burdened, interrupted, and temporarily destabilised by the powerful intrusions of his colonising and often ruthless father, though it has its lighter moments. There are many successes and achievements, and there is his moving compassion for his mother who is no match, in all senses of that word, for the man she married and whom Davidson is above all concerned to re-establish in the family story – his own quiet version of the empire writes back.

Davidson is an accomplished biographer, one of whose several skills is the vignette. There are, for example, snapshots of his father’s serially adopted and discarded mistresses. At one point, Davidson explains, he ‘had two women on the go, and seems to have alternated them. One was ... a toothy piece who displayed her bust like a built-in trophy, and didn’t have a great deal to say.’ The other, ‘pleasant and gently resilient ... told me, as generous to him [the father] as to me, how he had ended their affair by saying that his first duty was to his son. She said this a few times, with such sincerity that for a time I believed it – as a new and mitigating aspect of him I had not seen. But eventually I realised that once again he had used me – as a cover for returning to the buxom one.’ Then there was his father’s new wife, Eve.

Eve inherited her [mother’s] small stature; was bustling and purposeful and dressed practically in slacks. Over a strong jaw she had appealing brown eyes, and a pleasant subtle smile; she was less anxious than appraising. Generally she spoke in short sentences, occasionally breaking into what was less of a laugh than a cackle. Although her own art was pleasant and descriptive, she was drawn to the faces of Modigliani. Those slit eyes and blank faces looked pretty much alike to me, their severity a form of distancing from the world.

Jim Davidson Sr.

Jim Davidson Sr.

(image courtesy of Jim Davidson)Threaded through the machinations of his – to put it mildly – unlikeable father are Davidson’s schooldays, his self-deprecating account of his university career (‘In my formal studies – until the very end – I was not distinguished’), his slowly emerging recognition of his sexuality, his travels and life abroad, especially in South Africa and London, and his developing research interests as a historian and writer. As he grew and matured and began successfully to follow academic and intellectual paths, Davidson would have pleased any father who was not intent on competing with him, who was not potentially homophobic, not consumed with ‘constant self-dramatisation’, who did not have a sturdy ‘sense of himself as the centre of the action’, and who was not vaguely racist. ‘The more I read about “the white man”,’ Davidson muses, ‘the more I recognised my father. Like so many boys across the Empire – right up to the 1950s, when Biggles was still taking flight – he grew up on imperial romances.’ The educated, urbane son and the restlessly competitive, disapproving, and, in certain half-admitted ways, disappointed father is a volatile mix, and volatility – to use a word that scarcely does justice to the cataclysms of some of his father’s interventions – duly ensued.

The book’s recollected emotions end ‘[I]n tranquillity’, but the ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ brings only a troubled calm. Davidson is too canny an observer not to recognise tranquillity’s potential, after such insults, ‘malice’ and personal hurt, to come across as mere tranquillising, a species of cop-out. His father’s spirit, like Julius Caesar’s, is ‘mighty yet’; it has dominated the narrative, sometimes, especially towards the end, exasperatingly, and still ‘walks abroad’ enacting revenge through the unforgiving family. And so Davidson plays the last hand in this extraordinary, sombre, but utterly compelling memoir: he attacks the narcissist at his most vulnerable point: ‘I have come to accept [the behaviour of the family]. But my father’s ruthlessness is something else. I suspect he rather fancied a book being written about him ... Well, here it is. Not quite the book he wanted.’

Comments powered by CComment