- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

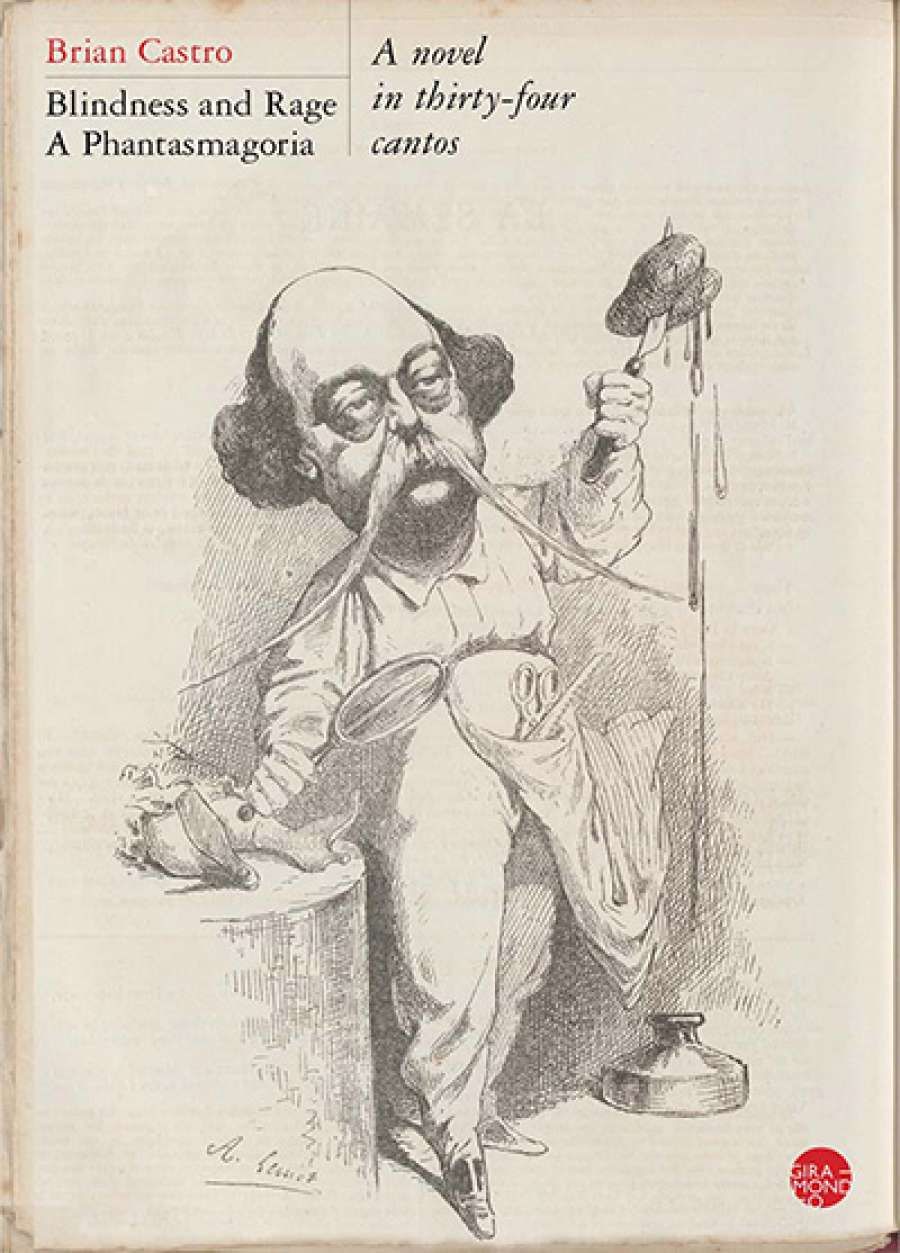

- Custom Article Title: Patrick Holland reviews 'Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria: A novel in thirty-four cantos' by Brian Castro

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Blindness and Rage

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Phantasmagoria: A novel in thirty-four cantos

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $26.95 pb, 224 pp, 9781925336221

Our Supermodern age is nostalgic. Ethnographer Marc Augé has suggested that those things which traditionally conferred identity upon us – namely geography and the narratives of time – have dissolved with the rapid communication of language and people around the globe. Blindness and Rage dismisses the linear river of time and acknowledges instead a pool of time we may dip into. Without warning or scaffolding, the novel moves between twenty-first century Adelaide to a Paris that seems made of many times, in which you can take photos on your iPhone but also meet long-dead authors such as Italo Calvino. The novel’s form is similarly playful. The thirty-four cantos recall the Onegin Sonnet, but also The Divine Comedy. There is even a contemporary, Parisian Beatrice. Indeed, it is an epic poem Gracq writes for the secret society, in ‘an age which had no idea of such a form’: ‘Relieved only by dreams / Of a vast and streeling sea / Of dangerous currents / And drowning sirens.’ The ‘drowning’ of sirens is crucial. It is Gracq’s relationship with death, and the relationship between writing and death, that is at the heart of Blindness and Rage.

Writing may bestow, of course, a kind of immortality; yet recent theorists have acknowledged the potential for writing to produce the erasure of the author. Foucault said writing is ‘creating a space in which the writing subject constantly disappears.’ The immortality function belongs to the past, the heroic ballads and epics; the effacement belongs to modernity.

Words have not been good to Gracq. Having intercepted a letter Gracq intended for a lover, his wife leaves him and dies in a plane crash. This death haunts the novel, but it comes to the reader, as to Gracq, in flashes and fragments. At last we feel that his wife’s accidental death over water, in no man’s land, motivated by the desire to escape social bonds at Supermodern speed, poses special representational problems for Gracq, the author of an epic. In the epic mode, death is typically meaningful: even a tragic death is attributable to some moral failing in the hero, or else a failing of the world to prove equal to the hero or heroine’s greatness of soul.

Blindness and Rage presents Gracq with a way out of language’s inefficacy, out of death, and the ironic literary posturing of the Fugitives. Having heard her music coming in from the apartment next door, Gracq enters a relationship with pianist Catherine Bourgeois. She is an enemy of the Fugitives, and as Gracq’s relationship with her deepens, his cancer goes into remission. Here, Castro makes an extraordinary link between cancer and irony, suggesting the former is a disease of modern cynicism and intellectual superiority, the refusal to be taken in. Just so Gracq determines to: ‘Go deluded into that dark night / And try not to live half a life / In perpetual treatment for cynicism.’ And so it is he devotes himself to Catherine, whose name he reconstructs, rather than deconstructs, to make her the more ideal (‘Her name, she said, was Catherine, / A name of magic and torture, / A saint upon a wheel of fire, / Queen with a carriage’).

Brian CastroGracq has been searching for language that speaks directly to experience, just as the notes of Catherine’s piano refer to no signified beyond themselves, but are their own truth. Gracq does not complete his book. At last, as Wittgenstein said we must when language fails us, when we confront life’s great truths, Gracq turns to silence. His travels take him to the Far East and, at last, back to Australia, where the reader awaits the denouement with Catherine.

Brian CastroGracq has been searching for language that speaks directly to experience, just as the notes of Catherine’s piano refer to no signified beyond themselves, but are their own truth. Gracq does not complete his book. At last, as Wittgenstein said we must when language fails us, when we confront life’s great truths, Gracq turns to silence. His travels take him to the Far East and, at last, back to Australia, where the reader awaits the denouement with Catherine.

Blindness and Rage is a novel capable of superb humour. This when Gracq laments old age and the coming of death: ‘I am a hollow man upon life’s station / where tall weeds grow in cracks, / turning desire in means winds, G-strings / stretched over emptiness.’ And it is capable of such exquisitely realised tragedy as this when speaking of the letter that undid Gracq’s marriage and led to the death of his wife: ‘And for the brief pleasure of a girl / Who he supposed would turn out ideal, / No one will meet him in the underworld.’

The world becomes richer when I read Castro, and I think Blindness and Rage is his finest book.

Comments powered by CComment