- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: John Rickard reviews 'The Enigmatic Mr Deakin' by Judith Brett

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

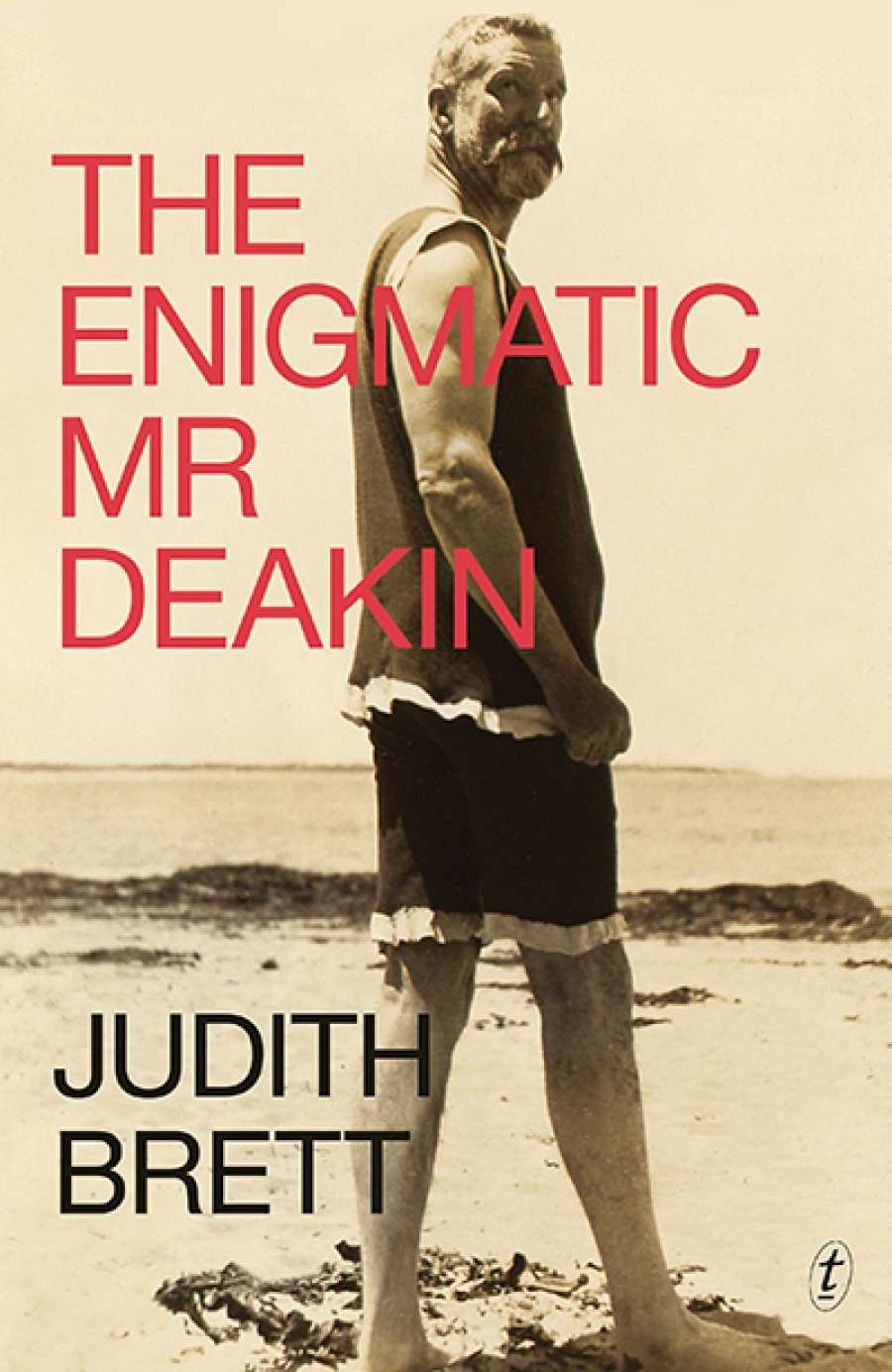

- Book 1 Title: The Enigmatic Mr Deakin

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $49.99 hb, 490 pp, 9781925498660

Deakin’s story is a complex one, because in a sense he had two lives – the public career centred on colonial and federal politics, culminating in his three terms as prime minister (1903–4, 1905–8, 1909–10), and his intensely private inner life, a continuing meditation and negotiation with his god, which his family and friends knew little about. La Nauze provided a masterly survey of Deakin’s political career, but was uncomfortable with his inner journey of faith and doubt. Brett’s great achievement is to bring the two together and show how each impacted on the other, a dialogue that could be either inspirational or a cause for frustration and guilt. Thus in turn she places Deakin in the context of a closely knit family in which there were developing tensions.

Almost from the start, ‘Deakin knew he was special’. He was the centre of attention in the small Deakin family: he was William and Sarah’s only son, and his elder sister Catherine, rather than resenting this precocious new arrival, ‘worshipped the baby as I have the man during all our lives’. He was full of energy and enthusiasm, a voracious reader and remarkably articulate; indeed he could instinctively command an audience. He was at first uncertain where to deploy his talents. He studied law at Melbourne University, and briefly and unsuccessfully went to the bar, while fantasising about a career on the stage. He threw himself into the spiritualist movement, which, with orthodox religious dogma under attack, had the attraction of novelty with the drama of the seance; he found that he had a gift as a medium, and within two years was presiding over the movement’s Sunday school. It was through his spiritualist connections that he met his future wife, the ‘graceful, translucent’ Pattie Browne, who had the distinction of being a child medium.

Still undecided about his future career, Deakin did some casual journalism for The Age, which was owned by David Syme, the acknowledged powerbroker of Victorian politics. It was through this connection that he was, as he famously put it, ‘whirled into politics’ in 1879 at the tender age of twenty-two. By 1883 he was a minister in a government coalition of conservatives and liberals, and two years later had become the leader of the liberal faction (this was a time when parties, in the modern, organisational sense, hardly existed). In the depressed 1890s he withdrew to the backbench and devoted himself to the federal cause, which in turn led to his crowning achievements in the federal sphere from 1901 until his retirement in 1913.

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin

(National Library of Australia, Wikimedia Commons)The young Deakin had a certain glamour: tall, charismatic, with eyes described as ‘mesmerising’ and ‘the compelling physical presence of a great actor’, he attracted both mentors and followers. Among the former were the conservative James Service and the radical Graham Berry. Brett stresses the importance of oratory in nineteenth-century culture. Political meetings were the lifeblood of democracy. Speeches two hours long were not uncommon, and Deakin’s astonishing ability to shape a speech, bringing the audience with him to its triumphant conclusion, was much remarked upon. His legendary (and much shorter) Bendigo speech to the Australian Natives Association in 1898 had such an extraordinary impact that it put an end to The Age’s opposition to the draft Constitution and ensured the success in Victoria of the referendum that followed.

Just as Brett is careful to place spiritualism in its ideological context to explain its appeal, so she is insistent that when interpreting the Deakinite policies of the early twentieth century, sometimes described as ‘the Australian Settlement’, ‘we need to exercise our historical imagination’, particularly to understand how Australians could regard White Australia as ‘an expression of high ideals’. Yes, of course the racist sentiments expressed then are abhorrent to us now, but, as Brett points out, the nineteenth-century ideal of the nation-state was bound up with the attainment of self-government and political democracy: for Deakin ‘the unity of Australia is nothing if it does not imply a united race’. And he was capable of holding this belief while having a great interest in Eastern religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism.

And it should not be thought that this is an uncritical biography. Brett scrupulously details Deakin’s investments in the 1880s when he succumbed to the Melbourne boom mentality: he was on the board of four companies that collapsed and was chairman of a building society which went into voluntary liquidation. He lost his own and his father’s money, which was a cause for guilt and shame, but, when forced to go back to the bar to maintain his middle-class income, cool pragmatism took over, and he defended in court several prominent landboomers who fell foul of the law. And Brett is clearly surprised and disappointed – as I am too – that a man of such intellectual curiosity and wide cultural knowledge had no interest in the Aboriginal people and their culture.

Earning an income and providing for his family was always an issue for Deakin. This partly explains his secretly writing as an Australian columnist for the London Morning Post from 1900 to 1913, even when he was prime minister. One senses a certain ironic piquancy when he wrote about himself, and Brett’s title, The Enigmatic Mr Deakin, is a phrase from one of his despatches. He took elaborate precautions to disguise his identity; indeed, if it had leaked out it would have been a political disaster.

Australia's first Prime Minister Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin

Australia's first Prime Minister Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin

(National Library of Australia, Wikimedia Commons)

For a man of such intellectual capacity, blessed with an extraordinary memory, it was a tragedy that from 1907 he was conscious of his mental world decaying. The main concern of his private reflections became to chart his own decline. As the book approaches the end of his career, there is a slight sense of haste in bringing this remarkable story to a close. The crucial 1909 fusion negotiations between the protectionists and free-traders are dealt with a tad too briskly, and Brett doesn’t notice that Deakin’s one-time close friend, Fred Derham, was a dominant figure in the Victorian Employers Federation, which, in league with interstate employer associations, would in large measure be funding the new party. If I have a criticism of the book as a whole, it is that I would have appreciated a firmer sense of structure, though maybe its thirty-six sometimes quite short chapters are expressly designed to encourage and engage readers. And it is a pacey, colourful narrative.

This is a fine biography – accessible, perceptive, and, in the best way, sympathetic. Deakin has found the interpreter he deserves for a modern audience. And if Deakin doesn’t fit as ‘a representative Australian figure’, perhaps that is precisely the point of his story – that politicians should be various, so that it is possible for a well-read, imaginative intellectual, with a talent for communication and compromise, to be an appealing and successful prime minister.

The ‘Australian Settlement’ associated with Deakin has received a bad press from neo-liberals, but the growing disillusion with privatisation and the corruption it has legitimatised makes the Deakinite agenda, with its reliance on a proactive state, look not half so bad. Perhaps the last word should rest with the patron saint of the Liberal Party, Robert Menzies, who, incidentally, was not a neo-liberal. He described Deakin as ‘this remarkable man’ who was Australia’s greatest prime minister.

Comments powered by CComment