- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Echoes and ashes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Now eighty, Felix, whom we met in two previous novels by Morris Gleitzman, is living in hot dry country Australia. In Once (2005), little Felix escaped from a convent, desperate to find his parents, not understanding that they had left him there in an effort to protect him. In Then (2005), he was ten. After jumping from a train bound for a concentration camp, he struggled to hide himself and six-year-old Zelda, who was not even Jewish, from the Nazis in Poland.

- Book 1 Title: Now

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking $19.95 pb, 176 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

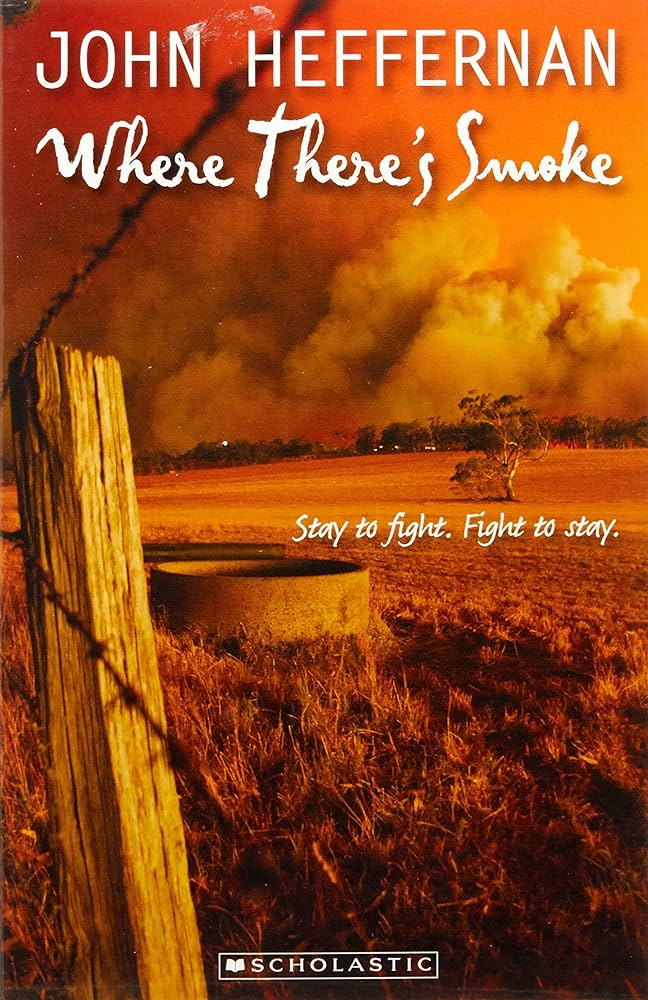

- Book 2 Title: Where There’s Smoke

- Book 2 Biblio: Omnibus Books, $17.95 pb, 205 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Now brings Felix’s story up to the present. Like many Jewish survivors of World War II, Felix was brought to Australia for a better, safer life. He became a surgeon, famed for his skill, compassion and, fittingly, for saving the lives of many children. Now he has retired and been joined by his young granddaughter, Zelda, named after the child whom Felix tried to protect in Poland and who was all he could call family. Zelda’s parents, also doctors, are currently working to save other lives in Africa.

Felix is frail, his legs still weak from spending two years hidden in a pit during World War II. His hands tremble too; he may have Parkinson’s disease. Zelda, struggling to be accepted in a new school, is nevertheless determined to make the most of her beloved grandfather’s eightieth birthday. This includes a stressful trip to the city for a grand celebration at the children’s hospital where Felix worked and was revered. Zelda, all by herself, organises a significant gift for Felix, bakes a cake and stages a picnic party. Her efforts sometimes go awry, causing her misery and confusion, but Felix and Zelda are tuned in to each other’s needs and emotions.

There are echoes of Felix’s war experiences everywhere. Zelda works hard to understand the implications and importance of his memories, experiences and the one tiny locket that belonged to the first Zelda. Those who have read the first two books would wish Felix a peaceful old age, but this is not to be as he and Zelda are caught up in the horrific events of the Black Saturday bushfires. Both are in danger but deal with life-threatening situations with resourcefulness, intelligence and heroism. Gleitzman has a finely honed ability to lighten the grimmest situations with just enough humour to avoid sentimentality and despair. Often he uses the dog, Jumble, to distract Zelda and the reader from the harshest moments.

Gleitzman strives to show that, despite what befell him, Felix went on to live a good and immensely productive life. We know that Felix achieved his aim to be the best kind of human being he could be. Gleitzman clearly also wanted to complete the cycle with another Zelda and to show the possibilities for young and old to contribute and be selfless.

However, when the parents return after the bush fire emergency, Zelda tackles them. She says: ‘In our family … there’s something we do a lot. The parents always leave the kids. It happened to Felix, it happened to Dad and it happened to me. I think we should stop it.’ Both parents recognise the truth of this. Then Zelda, as narrator, says: ‘I give Mum and Dad a smile, so they can see that speaking up doesn’t mean you stop loving them.’ Herein lies one problem with Now. Much of what Zelda is made to understand, articulate and endure seems beyond even the most sophisticated primary schoolchild. Zelda’s voice does not ring as true as those of the earlier Felix and Zelda, and the bushfire situation registers awkwardly as a conclusion to what is essentially a Holocaust story. Despite these reservations, Morris Gleitzman has written another book that is totally absorbing and shows readers what living as a good human being might mean.

John Heffernan, in Where There’s Smoke, uses the Black Saturday bushfire catastrophe as a narrative frame and context. Like Zelda, Luke is having a hard time at school. Being new and small, he comes in for his share of aggravation. But he’s game. Luke and his mother have been on the move to evade a violent father, who still looms. Now, thanks to the enormous, big-hearted and aptly named ‘Tiny’ Cobb, they have found a home in remote, idyllic Edenville: ‘It was almost too good to be true. A whole year without running.’ Luke’s mother works hard to make ends meet. Luke even makes a friend, Sarah, and life looks good.

Tiny is a ‘character’, probably of Baltic descent. Heffernan has fun with his mangled language. It is becoming hotter; the fires threaten and then swoop. The story slides from being domestic and character-driven to one of adventure, survival and heroism. Imagining and presenting the complexity of such an intense bushfire situation is a huge challenge for any writer, and at times Heffernan’s story loses focus and credibility. The chaos and ferocity of the fires propel most of the action and largely determine how the characters behave. Of course Tiny, Luke and his mother shine, but others rise to the occasion too. This is a readable and engaging tale.

Comments powered by CComment