- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Markolatry

- Article Subtitle: Loving detail in a flawed biography

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ernest Hemingway once wrote that ‘all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn’. We might add that Oz Lit owes Twain a little something, too.

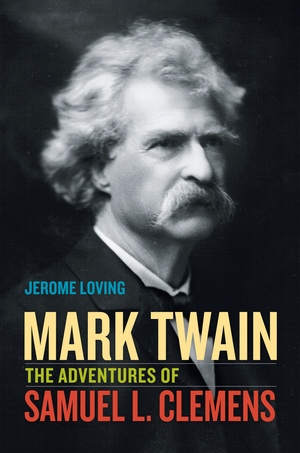

- Book 1 Title: Mark Twain

- Book 1 Subtitle: The adventures of Samuel L. Clemens

- Book 1 Biblio: University of California Press (Inbooks), $59.95 hb, 491 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

As Jerome Loving’s impeccably researched and exasperatingly flawed biography suggests, the posthumous reputation of these writers has also followed a similar course. Just as Lawson’s eminence now has less to do with literature than with nationalism – he is revered, like a flag or some natural wonder, rather than studied or relished in terms of his literary achievement – so too does Twain, who died a century ago this year, require saving from an idolatrous patriotism that obscures his flaws and more complex virtues.

Loving, alas, brings his own brumous weather to the life and work of Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835–1910). Although the biographer’s questions are clearly laid out – how is it that Twain became so fêted with so few genuine literary achievements to his name? how could a humorist have produced serious, lasting work? how could one be an artist who, in Van Wyck Brook’s words, hated art? – his answers, which show how America’s brute reality shaped a man who, in turn, shaped that nation’s idea of itself, are often lost in a haze of biographical detail.

This is not a failure of scholarship, since Loving has evidently toiled to assimilate tranches of material that have come to light in recent decades (5000 letters alone, since Justin Kaplan’s standard Life in 1966). It is more a problem of focus and style. In Mark Twain: The adventures of Samuel L. Clemens, the biographer has set out to capture, in ‘short chapters, or vignettes’, something of the restless, segmented, episodic life of its subject. Problem is, neither man sits still long enough to allow the deeper and more sustained story to be told.

Samuel Clemens was born twenty-eight years before becoming ‘Mark Twain’, in Missouri; the sixth of seven children, of whom only three reached adulthood. Instead of money, the young Twain inherited pseudo-aristocratic Southern attitudes from his father, who died when he was eleven. It seems the young Clemens could not tolerate free blacks’ uppity ways, and that his brief, undistinguished Civil War experience was with a band of Confederate volunteers.

Loving races to keep up with Clemens’s early peregrinations. At twelve, he was a printer’s apprentice; at fifteen, a typesetter for the Hannibal Journal, then owned by his perennially hopeless brother Orion. (It was not long before he was writing sketches and articles there as well.) At eighteen, he lit out for the metropolis and worked as a tramp printer everywhere from Cincinnati, Ohio, to New York City, where Walt Whitman claimed to have met him. The poet later described Clemens as ‘a man after old-fashioned models, slow to move, liking to stop and chat’.

Clemens was twenty-two when he found his way home to Hannibal, Missouri: the river-port town that was to become, in the St Petersburg of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), capital of Mark Twain’s empire of the imagination. Loving is particularly strong on the period Clemens spent as a trainee pilot on various Mississippi steamboats. It was highly paid, highly skilled work, undertaken by risk takers who outranked even the boat’s captain when called upon to guide the craft.

It turns out that Clemens was at best a mediocre pilot; at worst, a threat to himself and others. Yet the time he spent on the river was an education in something larger: he was a brilliant student of a world that was, with the coming of railways, set to vanish. It was also during this time that the writer’s younger brother, Henry, was killed in a riverboat explosion. Even though it was the outbreak of Civil War that officially expelled Twain from his paradise, the reader intuits that it was the guilt engendered by this event that kept him away. It would not be until Huckleberry Finn, decades in the future, that he would make a triumphant return.

In the meantime, however, Clemens entered an unsettled maturity. He was obliged to fail, not just as a pilot but as a soldier and a silver miner too, before realising that the true worth of this accumulated experience lay in its literary expression. Although he had used pseudonyms before, the day he began writing as Mark Twain marked the beginning of a new life. It also meant the death of the old.

Loving’s often-made point is this: it was the adventures of the man Samuel Clemens that the writer Mark Twain cannibalised for his success. From his inveterate travels west and south in the United States came the early frontier Feuilletons, short stories, and wildly popular lectures; from the more exotic and ambitious trips undertaken during his emergence as a popular writer – to Hawaii, the Holy Land, Europe and England – came material for novels, more lectures, and travelogues fuelled by satirical broadsides against Old World decadence.

Most significantly, though, it was his move to a grand house in Hartford, Connecticut – the epicentre of Yankee literary aristocracy – and his acceptance into the ranks of its Brahminical class that obliged Twain to dig ever deeper into his past in order to maintain an extravagant present. Luckily, the seams were thick. Writing made Clemens a rich man: yet some essential philistinism in his nature, a desire to be seen as a canny early adopter of cutting-edge technology, pauperised him once again. Loving doggedly traces Clemen’s doomed obsession with the Paige Compositor, and offers ample proof of Twain’s ‘lifelong losing streak’ as an investor.

Yet it was success – for he always wrote himself out of trouble – that spoiled Samuel Clemens. As Loving shows, it was ruinous for his art. Manuscripts were picked up, shuffled, abandoned, bastardised or completed in a rush years later. Even his one indisputable masterpiece, Huckleberry Finn

bears the marks of a number of books he was working on simultaneously, with his usual fits and starts, not just the river books [Life on the Mississippi, for instance, where Huck is first introduced] but also A Tramp Abroad and The Prince and the Pauper.

Loving cannot be faulted in laying out the day-to-day evidence of Twain’s contradictory character and of his paradoxical literary achievement. But, like the ‘psalm-singing cattle’ who raised the young Clemens’s ire during his world voyage on the Quaker City (the basis for The Innocents Abroad), the biographer dutifully admires every portrait in the Uffizi without leaving much time to meditate on the mystery of the Madonna con Bambino.

At his worst, Loving musters details into each chapter as into a stockyard, where the dust and bellow of corralled facts make for a busy din. Themes are reiterated to the point of absurdity (‘the mysterious stranger’, a reference to Twain’s late works in which Satan is the protagonist, is ticked with metronomic regularity every dozen pages or so), while metaphors are mixed so often that the prose turns a sort of khaki.

Nonetheless, the biographer admires his subject and knows him well, and his folksy style can disguise a sharpness that matches its subject. Loving eventually does find space enough to suggest that the myths that made Twain the most famous writer of his day deformed his life and personality. It was the clown’s mask that hid the cowardly soldier who fought on the side of slavery. It was the Puritan who, in rejecting his religion, ended up worshipping Mammon instead.

Perhaps, too, it was the very stolidity of Twain’s mid-life success – the respectable family of noble wives and daughters, bent on civilising him; the vast house, its foundations sunk deep in place as the New England society gathered round – that sent Clemens’s mind back to the Mississippi River: a personal longing that, as V.S. Pritchett observed, became ‘the channel of the generic American emotion which floods all really American literature – nostalgia’.

Comments powered by CComment