- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Here's trouble

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One day soon, instead of meekly thanking the Editor for another memoir, I’m going to scream. Not another damned life story, confession, self-exploration! I’m fed up, I’ll shout – fed up with women (because they always are) whose only way of writing about their times is to plonk themselves at the centre (which they are, in a literal sense) and to define everything through their own feminism, jacket, migraine, dog, marriage, job or dependency.

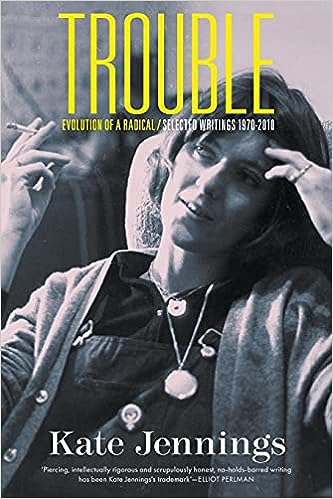

- Book 1 Title: Trouble

- Book 1 Subtitle: Evolution of A Radical / Selected Writings 1970–2010

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.95 pb, 330 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

I’m going to rail against authors who complain that they have been ignored when they haven’t. In one of the introductions to the nine sections of Trouble, Jennings reckons her 1993 collection of essays, Bad Manners, was ignored. Well, hell, I read it (and there are many essays from that book reprinted in Trouble), and lots of people I know did too, and I distinctly remember good reviews. It wasn’t exactly A Confederacy of Dunces, although for the life of me I can’t find it on any shelf at the moment, so perhaps she’s right. Jennings reckons she’s always ‘rubbing the fur of [her] own cat backward’. She’s a bundle of contradictions, congratulating herself in one breath that no one else agrees with her, and complaining in the next that others are always disagreeing, that she’s ‘pissing in the wind’. Much of her literary energy exults in being sometimes contrary, sometimes grumpy and sometimes self-justifying. Coinciding with the release of Trouble, an interview with Phillip Adams on Radio National found this unlikely pair performing an orgy of mutual congratulation, each rubbing the other’s fur forward until the purring drowned out any serious discussion of Jennings’s writing. You could sense a version of personal triumph in Jennings’s demeanour: I have collected myself; therefore, finally, I am. And why not! She’s been immoderately, stylishly going against the grain for decades, fighting her own demons, writing with guts, often about herself.

Have I mentioned how much I enjoyed Trouble?

Reading these essays, poetry and a little fiction is rather like pulling out buffalo grass, something I’ve been doing in equal measure while reading Trouble. This cussed, indestructible plant is part pain, part pleasure to wrestle with. You can simply poison it off and leave the gross tangle of the mother roots to wither away. But they are relentlessly resilient; shoots will appear again. And once you start pulling it out, it’s hard to stop, even when you need a strong back and spade to dig down and under the entrenched roots. There’s something addictive about pulling it out, yanking it until you’ve loosened enough of a great clump of roots so that one long, thick, strong, living length will pull away for up to a metre and bring with it the green shoots of grass at the end. You’re dirty, tired, there’s soil in your eyes and under your fingernails, but you’ve made progress and part of the sadomasochistic pleasure is that by untangling the roots and releasing the long tendrils of more recent grass, you get to understand its remarkable tenacity, and the rude health of the aboveground green.

Have I told you how much I enjoyed Trouble?

A group of interviews Jennings conducted with three Australian writers long resident in New York, as she herself is, forms a substantial section in this collection of writing, which spans forty years. Two were commissioned by Island in 1991 and 1992, and the third, with Ray Mathew, was published in Voices in 1993. Asked if he enjoyed returning to Australia, Sumner Locke Elliott replied that it was exhausting, and went on to say, ‘Have you met David Malouf? Wonderful writer. He summed it up for me. He said, “Oh my god, Australians, we are a grudging race.” I don’t know whether it is still like that, but oh that grudging praise!’

Shirley Hazzard, who judged Elliott one of the wittiest men, mentioned to Jennings ‘the Australian tendency toward derision’ when we are uneasy, and Jennings replied, ‘To deride and mock is almost a national pastime in Australia’. Hazzard agreed that this ‘can seem habitual’. Later, Hazzard, whose elegance of phrase always impresses, responds to Jennings’s avowal that women don’t take themselves seriously enough, and says, ‘To have some style, some true, inward self-possession is a pleasant thing. In its benign form I like and envy that. In its malignant form, as a posture, it is absolutely awful ...’

Mathew, who died aged seventy-four in 2003, spoke about being praised for a play he wrote when still in primary school: ‘It certainly was fixed that this was a way to earn praise.’ Yet Hazzard agreed when Jennings said that ‘Australians are suspicious of people who have a way with words’. These interviews are the grace notes in a book devoted to the author herself. It’s interesting that they are included at all, so divergent are they from the subject at hand, except for the bundling of four Australian writers who left Australia so long ago but didn’t become part of the Greer/Humphries/James/Porter mythology, perhaps because they went to America.

Did I say that Trouble edges towards the unputdownable?

Kate Jennings, your Trouble is like my entrenched, invasive grass: the old roots dying off but still begging to be excavated (three inclusions from the 1970s, one of them the embarrassment of the Front Lawn Speech, all cracked bluster, hysterical profanity, crazed revolutionary feminist tactic and gross immoderation; another, the introduction to Mother I’m Rooted, the 1975 anthology of Australian women’s poetry that Jennings compiled); the more recent underbelly of roots in good nick (the Bad Manners essays, for instance, and some poetry published in the 1990s); and the long tendrils of healthy grass dependent on the knotted and tangled older growth.

These recent essays (substantial writing on the American elections and the financial brouhaha, and a couple of long essays written for The Monthly) are the central strength of Trouble, though it should be said that Jennings’s writing now is little different from her writing then. She has a way with words and is the owner of a crusty, muscular style. There’s no dross. Her voice edges towards the conversational, in part because it is always so personal, but the literary voice is much more finely honed than that suggests. At its best, this voice is invigorating, punchy and intelligent. She’s very good at judging the right tone for outrage (Wall Street and bankers, for instance), but it is difficult to stomach her many petty (but not petty to her) furies and quarrels with her Australian contemporaries in general. The very best that can be construed from Trouble is that, without changing her literary voice, without turning her back on her roots, she has grown up.

‘I’m not immune to wanting to set a few things down for the record,’ she says in the preface, but this isn’t anything like a conventional memoir. All autobiography is selective, and, as a ‘stand-in for a memoir’, Trouble is as reticent, selective and personally well groomed as you might get. By using only published work to tell an approximate life story, a gaping hole stares at you from the late 1970s until the early 1990s. It’s hard not to think about the hole. Jennings reckons she finds it easier to write novels than non-fiction, but Trouble belies that statement. She has not been a prolific writer of fiction; she’s no Philip Roth, Joyce Carol Oates, Shirley Hazzard or David Malouf. She’s trouble.

Comments powered by CComment