- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Going Latin

- Article Subtitle: Latin America as imagined landscape

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

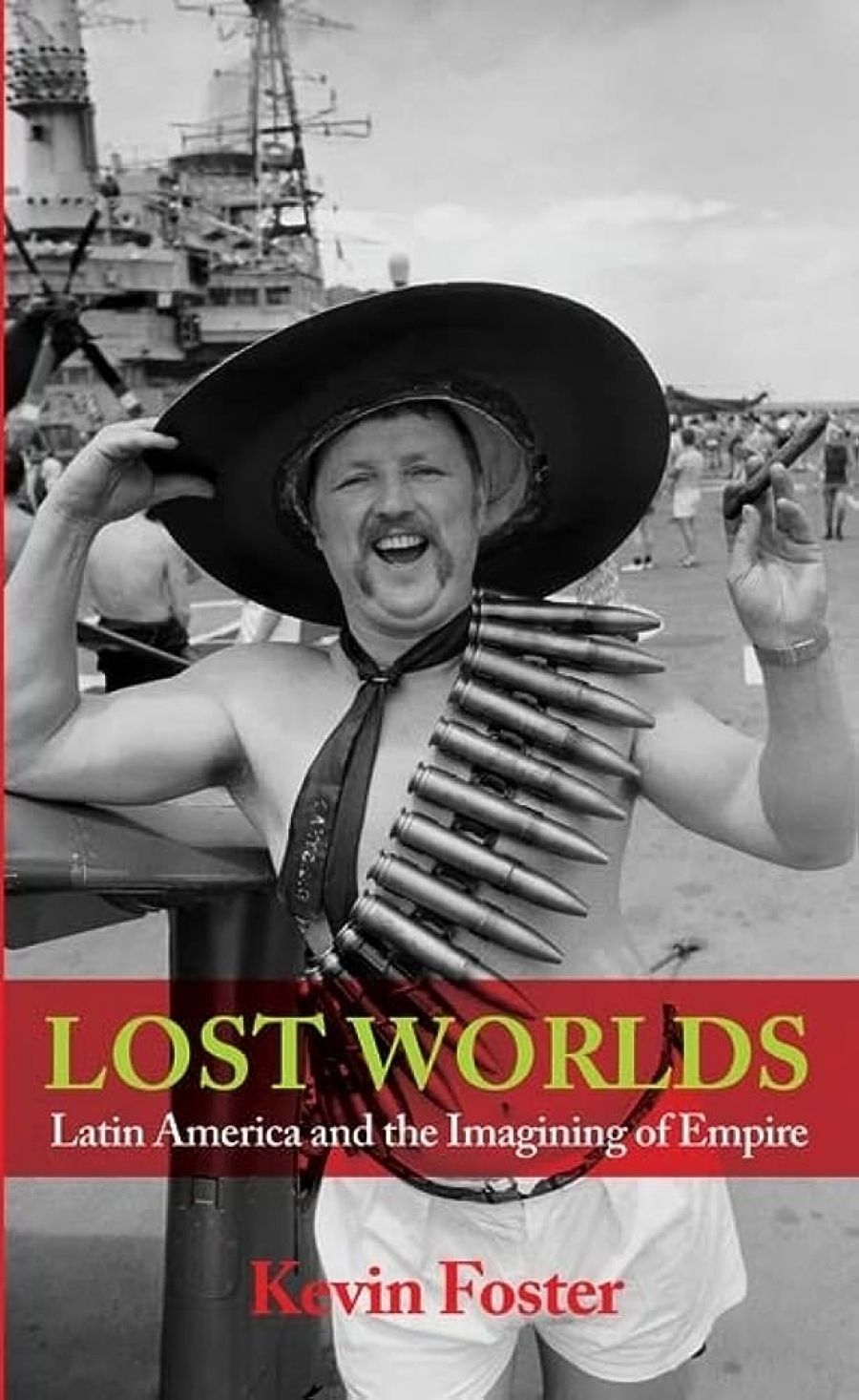

Start with the cover, cunningly designed to provoke a double take. What at first glance appears to be a cigar-chomping Mexican bandido in an oversized sombrero proves, on closer examination, to be a grinning British soldier celebrating victory in the Falklands. All he needs to go Latin is a big hat, a bullet-studded bandolier and a cigar. Three props conjure a chuck wagon full of clichés. The sombrero speaks of braggadocio and machismo, Hugo Chavez, Manuel Noriega, Juan Peron, generalissimos and juntas. But also of laziness – a hat to pull down over your face when, slumped against the adobe on a dusty side street, you sleep off the tequila. Poverty born of sloth, whose only remedy is to slip north across the Rio Grande: wetbacks, drug runners, illegals.

- Book 1 Title: Lost Worlds

- Book 1 Subtitle: Latin America and the imagining of empire

- Book 1 Biblio: Pluto Press, $59.95 pb, 279 pp

Kevin Foster points out that the reason why these stereotypical images of Latin America live on in British and American imaginations is that, behind every one of them, lurks a wish for fulfilment. Lots are about escape, not so much to where you can get away from it all as to where you can get away with it all. Such as Max Bialystock in Mel Brooks’s The Producers, who lures Leo Bloom into his crooked scheme, singing, ‘Oh Rio – Rio, Rio, Rio’. Or unextraditable Ronald Biggs, sipping margaritas and ogling girls from Ipanema while English coppers grind their teeth. Not to mention South Carolina Governor Sanford, who told his staff he would be trudging worthily along the Appalachian Trail before flying off to join his Argentinean mistress in Buenos Aires. Throw away your inhibitions and slip into the Carnaval procession; folks back in Peoria and Lake Wobegon will never know.

Other wishes revolve around easy money. One implication of the Mexican snoozing beneath his sombrero is that slothful Latins prefer leisure to work, ignoring untold riches just waiting to be plucked from the earth by enterprising outsiders: dreams as old as Coronado’s search for the city of gold and the South Sea Bubble (a South American, not South Pacific venture), which ruined Handel and Newton. If you can’t make it here, you’ll make it there. A whole range of other stock images mix promises of material plenty with plenty of sex. Brazilian Carmen Miranda, swaying seductively beneath her preposterous tropical fruit hat, set the gold standard back in 1939.

Latin Americans’ struggles to make headway against the relentless tide of caricature have generally been as futile as Noël Coward’s ‘Nina from Argentina’, whose protest was to stop dancing.

She said ‘I hate to be pedantic but I’m driven nearly frantic

When I see that unromantic, sycophantic lot of sluts

Forever wriggling their butts.

It drives me absolutely nuts.’

….

And she could not refrain from saying that their idiotic swaying

And those damned guitarras playing were an insult to her race

And that she really couldn’t face

Such international disgrace.

Foster is on Nina’s side, but his main purpose in Lost Worlds is not to contrast the stereotypes with Latin American realities. It is to show how the clichéd images sustained a long British tradition of using Latin America as an imagined landscape where European and North American fantasies, fears and morality tales could be played out.

In 1516 Thomas More used the fictional South American island of Utopia as a platform from which to denounce the faults and follies of his own society. Displaying great breadth and depth of reading, Foster traces the variations Britons played on More’s theme in the succeeding five centuries. These include poetry, such as Robert Southey’s epic Madoc (1805), histories such as R.B. Cunninghame Graham’s A Vanished Arcadia (1901), which recounts the tragic misfortunes that befell the eighteenth-century Jesuit missions in Paraguay, and real-life efforts to create real utopias, as William Lane attempted in his South American settlement, New Australia, at the end of the nineteenth century. Lane’s venture embodied all that was best and worst in Australian trade union intellectuals of his era. While aiming to create a communistic society amidst the indigenous Guarani people of Spanish-speaking Paraguay, New Australia specifically excluded from membership any person ‘not knowing English so as to understand and be understood’ and ‘any person of colour, including any married to persons of colour’. In a fascinating aside, Foster calls attention to a parallel Paraguayan venture, Nueva Germania, which had been launched a few years before by the anti-Semite Bernhard Förster and his wife, Elisabeth, who was Friedrich Nietzsche’s sister. Their sinister objective was to renew the genius of the German spirit on South American soil and to perpetuate it through the breeding of a purified Aryan master race.

In a further variation on the theme, Foster turns to postwar British sports journalists who used Brazilian soccer as a vehicle for criticising the sorry state of English football. Completely ignoring the real reasons for Brazilian success, they hailed them as untutored natural athletes whose flair, grace and enthusiasm sprang from a pure love of the game, unlike the stodgy, slogging British professionals. The sports writers embraced Pelé as the black man whose ‘natural rhythm’ on and off the field represented everything English players were not.

Foster takes his title from Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912), one of his ‘Professor Challenger’ series of science fiction novels. A linear ancestor of Jurassic Park, it features a party of British explorers who stumble into a South American valley where dinosaurs survive and primitive men battle ferocious great apes. Like other adventure literature of its era, The Lost World is based on the premise that encounters with savages in undiscovered lands bring out the savage within us. Professor Challenger resembles Indiana Jones in scholarship, strength and agility, but not in modest demeanour. As his name suggests, he bullies not only savages but scientific adversaries and his own colleagues. In his climactic confrontation with the leader of the marauding apes, Challenger thrusts his prognathous jaw forward and bellows in anger. Looking from one to the other, it was hard to tell man from ape. As Foster observes, ‘For all the smug assurance of his evolutionary advantages, modern man has not left his more primitive self behind but carries his primordial savagery within him, and the least provocation might bring it to the surface and betray him.’ So said Joseph Conrad in Heart of Darkness (1902); likewise Rider Haggard in King Solomon’s Mines (1885) and several of his later novels, one of which, Heart of the World (1895), attracts Foster’s attention because of its Mexican setting.

Many readers may find themselves wondering whether the Latin American venue of this genre is necessary or just incidental. In a review of a book about ‘elephant smashing’ in central Africa written in 1894, Rider Haggard complained that as explorers pushed back frontiers of knowledge, they made life more difficult for his kind of writer. ‘Where will the romance writers of future generations find a safe and secret place, unknown to the pestilent accuracy of the geographer, in which to lay their plots?’ Once Central Asia and the Polar Regions had been mapped, they would have to cast their eyes towards other planets. Which is precisely what happened to science fiction. Could not Conan Doyle’s Lost World have just as easily been transported to the Yukon, the Congo or Jules Verne’s Centre of the Earth?

Eventually, Foster makes his way back to the subject of his cover picture. For him, the Falklands War epitomised the paradox at the heart of Margaret Thatcher’s promise to sweep away the social-democratic state while leaving the essential character of the nation intact. ‘When the Argentines invaded the Falkland Islands in April, 1982, Britain was unexpectedly confronted with a vision of its pre-industrial self, a community of hardy rural yeoman rudely menaced by a tide of invading machinery.’ For ‘more than two centuries British writers had journeyed to Latin America in quest or defence of the nation’s essential identity’. The Argentines were not just fighting the military. ‘Standing between the British and the embodied evidence of their essential identity, the poor bastards never stood a chance.’

Inevitably, in a book of two hundred pages, much gets left out. By excluding the West Indies, Foster bypasses the rich subject matter provided by Cuba and the Dominican Republic. What I most wished for, however, was more attention to the whole dystopian stream of writing about Latin America: nights of the iguana, whisky priests, Paul Theroux’s Mosquito Coast (1982) and, above all, Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano (1947). In these works it is not Latin America that fails or brings out the savage that lurks within civilised Westerners. Deprived of their customary support systems, the anti-heroes of these works fall apart. The disintegration of their dreams and psyches may echo the stereotypical faults of the nations in which they are set, but it is not caused by them. The fault lies within. The fear they summon is that our vaunted superiority is a sham. It is even possible, as Paul Keating reminded us – borrowing a piece of fruit from Carmen Miranda’s hat – that we might become a banana republic.

Comments powered by CComment