- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Tony Hughes-d’Aeth reviews 'Taboo' by Kim Scott

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When a new novel from Kim Scott appears, one feels compelled to talk not only about it as a work of fiction by a leading Australian writer, but also about its cultural significance. In this sense a Kim Scott novel is an event, and Taboo does not disappoint ...

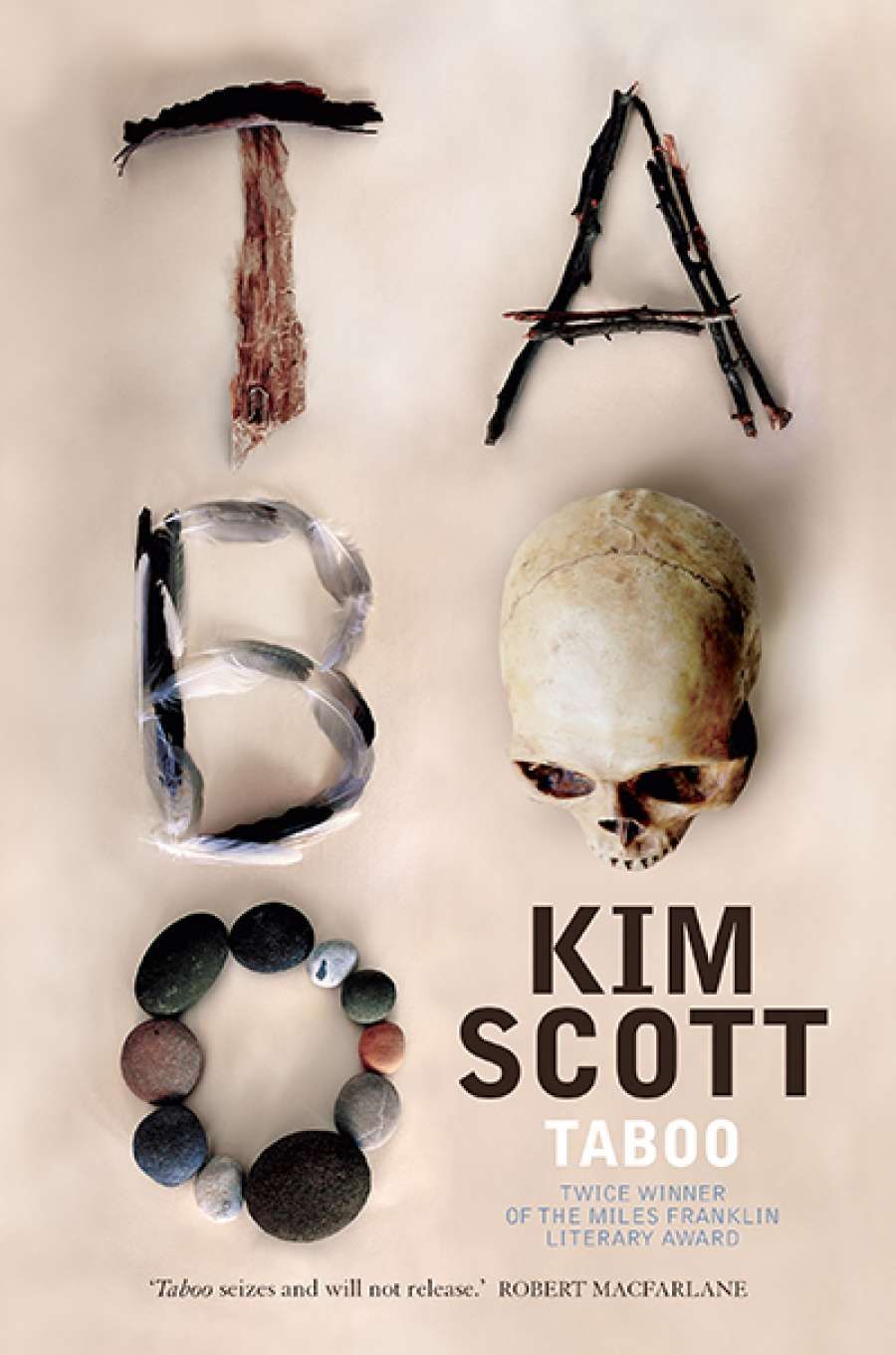

- Book 1 Title: Taboo

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador $32.99 pb, 271 pp, 9781925483741

That Deadman Dance took place on the south coast of Western Australia in a fictionalised Albany called King George Town in the early, and relatively peaceful, years of settlement. The contact communities of King George Sound become a kind of experiment in which we glimpse the historical opportunities that were lost as a more determined colonial avarice set in.

In Taboo, we move firmly into the here and now. If Benang was the great novel of the assimilation system, and That Deadman Dance redefined the frontier novel in Australian writing, Taboo makes a strong case to be the novel that will help clarify – in the way that only literature can – what reconciliation might mean.

The novel’s action is centred on the opening of a ‘Peace Park’ (or ‘Peace Plaque’, no one seems to quite know) in the fictional town of Kepalup on the south coast of Western Australia. The park/plaque was a reconciliation initiative of Janet Horton, who belonged to the historical society and was the wife of a local farmer, Dan Horton. Janet has recently died, and her grieving and religiously devout husband wants to honour her memory by bringing the park/plaque to reality. Horton has had his farm passed down to him through his ancestors and it is in the river valley that runs through this property that a massacre of local Noongar is said to have occurred in the 1870s. The massacre happened after the murder of one of Horton’s ancestors. How many died is not known, and Horton would prefer not to use the word ‘massacre’. It is a ‘hurtful’ word to his family, he explains.

The main thrust of the novel comes from the other side, from the descendants of the original owners, the Wirlomin people, the Noongar grouping with which Scott identifies. Early in the novel, a bus weaves its way through the more dilapidated neighbourhoods of King George Town (Albany), picking up the various Noongars whose kinship is to the Wirlomin people. Mostly middle-aged or older, they are travelling to a cultural retreat being run by some Wirlomin elders at the caravan park in Hopetoun. They are also going to attend the opening of the Peace Park at Kepalup.

Kim Scott

Kim Scott

Amongst their number is a young woman, Mathilda (‘Tilly’), who is in her last year of high school. Only recently has she met her father, Jim Coolman, a Wirlomin man. Coolman, dying of cancer, was in jail, where he had spent the majority of his life. Tilly’s mother was a white woman who suffered abuse in her short relationship with Jim. When Tilly met her father, he had drawn belated solace from reconnecting to his Noongar language as part of a prison program. He urged Tilly to make contact with her Wirlomin relations.

How the novel then unravels the complications of reconciliation is something I found utterly compelling. As with other Scott novels, the cast of Aboriginal characters in Taboo are not angels. Drug abuse and domestic violence are part of their lives. This clear-eyed approach to the social world is a recurrent feature in Indigenous writing, going back to foundational writers like Oodgeroo Noonuccal and Jack Davis. No one is quite what they seem in Taboo, for better and for worse. It is an important feature of the novel that the exact nature of the massacre is not known and can’t be known. At least, not known in the ways that we expect knowledge to exist for it to be relied upon in Western knowledge systems. The climactic encounter between the Wirlomin descendants and Dan Horton at the site of the massacre deserves be read and reread. It is not a set-piece in which the virtues of the Indigene are lined up against the vices of the colonist. It is a raw working through of wounded memory.

In South Africa, as is well known, there was a Truth and Reconciliation Commission into the apartheid years. In Australia, the truth of colonisation cannot call its dead witnesses to appear, nor offer them amnesty in exchange for honesty. But reconciliation in Australia depends on us evolving more profound mechanisms for coming to truth than the ones we have come up with so far. Counting the bodies in the historians’ footnotes is not going to get us there. Taboo is a powerful novel that offers something more than this.

Comments powered by CComment