- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Paul Giles reviews 'The Glamour of Strangeness: Artists and the lost age of the exotics' by Jamie James

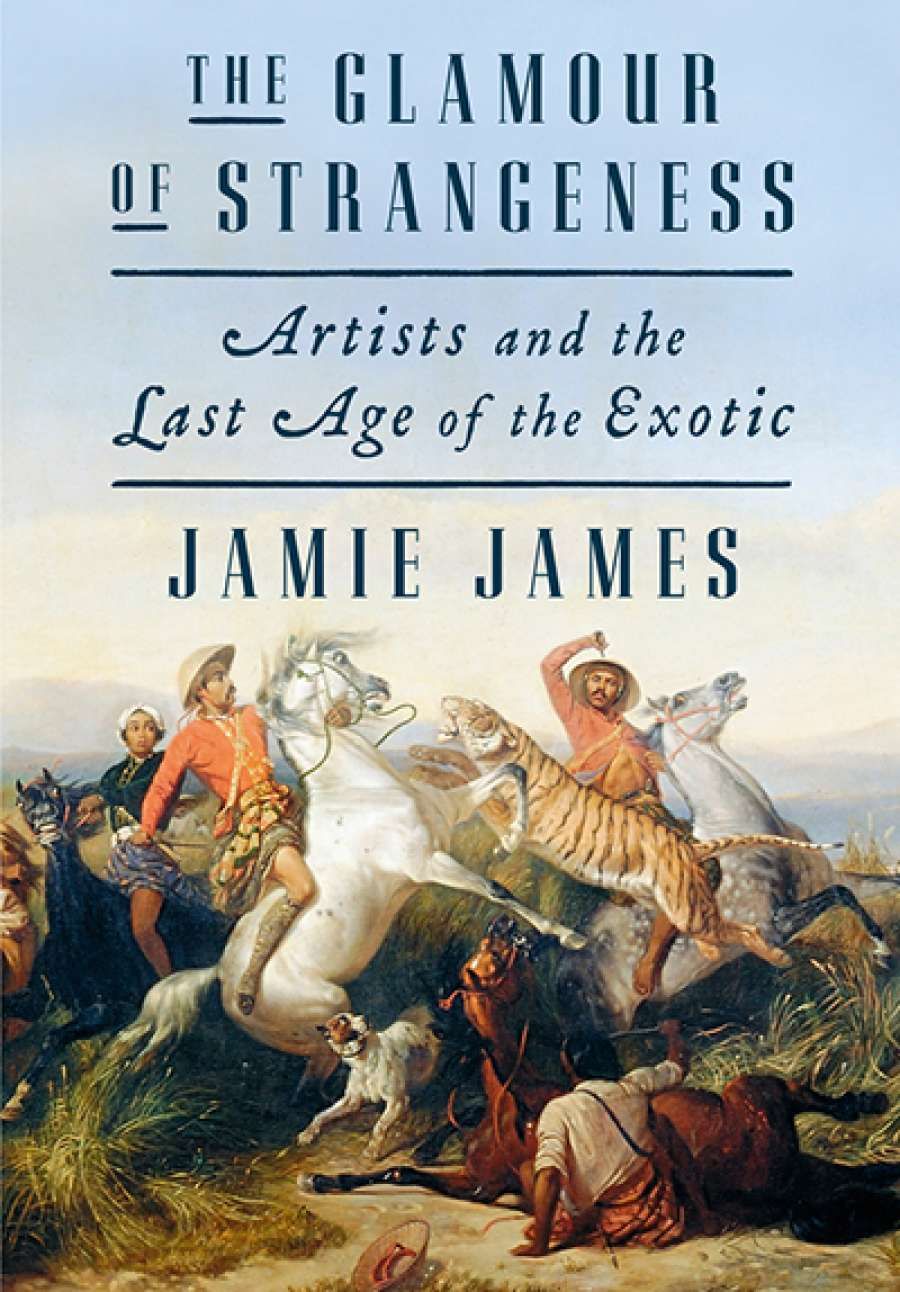

- Book 1 Title: The Glamour of Strangeness

- Book 1 Subtitle: Artists and the lost age of the exotics

- Book 1 Biblio: Farrar, Straus and Giroux $37.99 hb, 375 pp, 9780374163358

We might wish, however, that James had stuck to his original plan, for the sections of this book dealing with Javanese culture make for much the most compelling reading. The author himself, formerly a freelance arts journalist in New York, has lived in Indonesia since 1999, and the sections here treating Saleh’s painting (based on a ‘landmark exhibition at Indonesia’s National Gallery’ in 2012) and the work of Spies are fascinating, the latter being heightened by some excellent colour reproductions furnished by the New York trade publishers. It is also both surprising and revealing to learn about the extent of Hollywood’s engagement with Indonesian culture on either side of World War II. James discusses Honeymoon in Bali (1939, starring Fred MacMurray) and Road to Bali (1952, starring Bob Hope), as well as Charlie Chaplin’s visit to Bali in 1932, after the success of City Lights. Chaplin also developed ideas at this time for a feature film to be set on the island, but this plan never came to fruition.

Unfortunately, though, James attempts to expand his thesis to encompass a global version of the exotic, and this is much less convincing. He conceptualises his variegated subjects in terms of certain characteristics they shared: linguistic dexterity, artistic versatility (‘working in many media’), the fact that they ‘were all brave people’ and suffered premature deaths. But there is not even a nodding acquaintance here with considerations of how exile was a constituent aspect of modernism more generally; as many scholars have observed, exile was, for various reasons, more the norm than the exception among avant-garde artists in the first half of the twentieth century. James casts aspersions several times on systems of ‘feminist and postcolonial critiques’, but such hostility to what he calls academic ‘spinners of theories’ leaves him to construct a narrative of exoticism based upon nothing more than what he calls ‘sympathetic vibrations’ with his subjects. He finally excuses this impressionistic method by describing his account of ‘a group of artists’ who created ‘works in different media that span two centuries’ as merely ‘a thought experiment’.

Portrait of Raden Saleh, 1872

Portrait of Raden Saleh, 1872

(Wikimedia Commons)Such lack of clarity is particularly regrettable since James is so knowledgeable about the particularities and idiosyncrasies of Indonesia; he describes in illuminating detail how its culture arose from a conflict in the nineteenth century between Dutch and Javanese interests. Epigraphs from Baudelaire, Elizabeth Bishop, and others are strewn around the book, which reads at the end more like a heterogeneous collection of curiosities than anything resembling a coherent argument. (Herodotus, for example, is hailed and farewelled in one sentence.) The form of the narrative reflects this generic hybridity, mingling discursive prose with conversational colloquialisms based upon the author’s autobiography: Richard Halliburton, for instance, is described as ‘a Marco Polo for the Jazz Age’ and ‘already a quaint figure by the time I discovered his book in my grandmother’s library in Oxford, Mississippi’. This anecdotal style leads to an odd conflation of objective and subjective perspectives, leading the author to admit that ‘while I was writing this book in Bali and Lombok, I sometimes wondered if I was writing the story of my own life’.

Edmund White is thanked in the acknowledgments for making ‘some excellent suggestions that bore fruit’, and this whole enterprise carries the air of an intellectual flâneur sauntering past strange exhibits on the world stage. Taken on their own terms, James’s peregrinations are often lively and interesting, and he comments on a characteristically evocative scene set in a Peking brothel from Edmund Backhouse’s autobiography Décadence Mandchoue (1943), where to ‘evoke the timeless, radiant splendour of his night of paid sex, Backhouse quotes Homer, Sophocles, Euripides’, and a host of other cultural authorities. James aptly describes the overall effect of this as ‘not erudite so much as demented’, and though this would be an unduly harsh assessment of his own work, it does suffer from similar contortions, where disinterested analysis and sexual badinage are brought together in an enticing but not entirely convincing manner.

Comments powered by CComment