- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

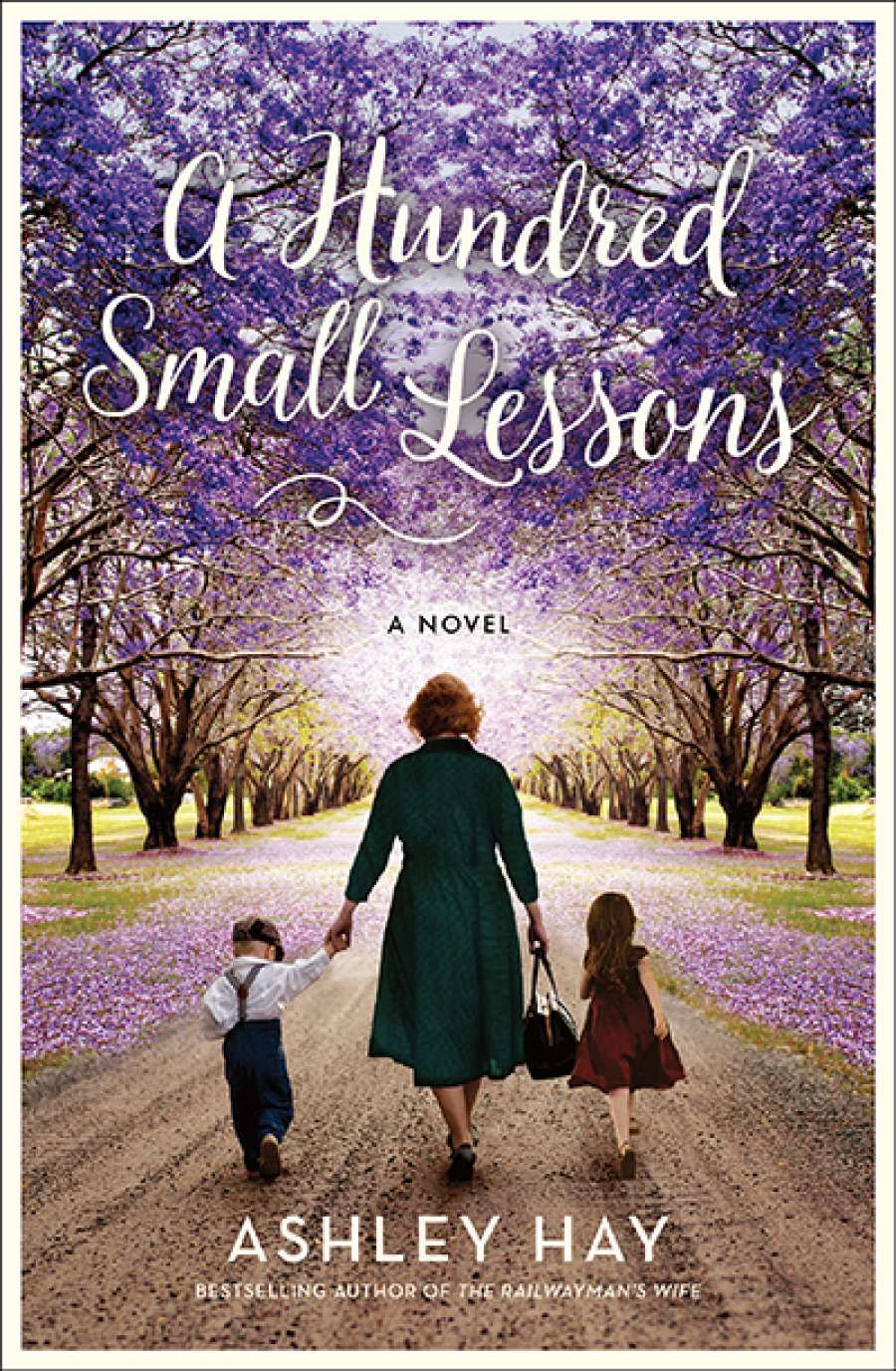

- Custom Article Title: Tessa Lunney reviews 'A Hundred Small Lessons' by Ashley Hay

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Hundred Small Lessons holds powerful truths, simply told. It is a story of parenthood and place, where small domestic moments, rather than dramatic public displays, are the links between people, the present and the past. Each moment occurs in and around a familiar, ordinary Brisbane house ...

- Book 1 Title: A Hundred Small Lessons

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin $32.99 pb, 384 pp, 9781760293208

Their Brisbane house stands for home which stands for motherhood, as though neither Lucy nor Elsie can under- stand how to be a mother without this house: ‘In their new house – Elsie’s house – the back door faced almost due east and Lucy loved that. One sure point in a floating world.’ The house, situated near a swamp that leads to the river, is vulnerable to flooding and wildlife, as well as to the transformations wrought by the occupants. Since more than one character proclaims how much they love Brisbane, the way it changes through the wet and dry, it is as though parenthood is so amorphous and consuming that Lucy and Elsie cannot simply love the role. Instead they must love the jacarandas and brown water, the crows and the tropical moods of the city. ‘This astonishing place: sit still long enough and the wildlife took such liberties, like there was only ever a porous border, at best, between what was outside and what was in.’

The doors to the house, the verandah, the garden fence, the river, the city, become the porous borders of a life transformed through parenthood. When they are open they are exciting yet dangerous; when closed they are safe but constricting. These borders are also between the past and the present. Elsie often notes how coincidence has shaped her life, and wonders how her present self grew from her past self, while Lucy wonders where her old self went. These questions are not easily resolved but hold much of the narrative tension.

Elsie and Lucy are explored, Ben and Clem are explained, but for a novel about parenthood, their children deserve more attention. Elsie’s daughter Elaine is always on the verge of becoming an exciting, dramatic character, especially because of her fraught relationship with her own daughter, Gloria. The novel suggests that Elaine’s and Gloria’s know-ledge of the filial relationship would not be composed of a hundred small lessons but rather of a few startling ones, a dark counterpoint to Elsie’s and Lucy’s constant striving to be good. Tom is too young to be capable of such startling decisions, but there is little sense of him beyond Lucy and Ben’s anxieties.

Ashley HayThe writing is clear and lyrical. Some passages achieve a subtle beauty, but often they become too explicit. A final sentence robs a paragraph of its power by straightening out the image’s ambiguities rather than letting the reader linger over the possibilities. As with Hay’s previous book, The Railwayman’s Wife (2013), a poem embedded in the text is the focal point; here, from Michael Ondaatje: ‘For his first forty days a child / Is given dreams of previous lives. / Journeys, winding paths, / A hundred small lessons / And then the past is erased.’ The eponymous poem becomes the pretext for an argument between Ben and Lucy. The fight holds all of the book’s ideas – memory, parenthood, identity, place – and the action is pacey, but the poem compels the reader to stop and linger, to bring the idea of porous borders into the sentences. Hay employs powerful ideas; for example, that small instinctive actions have huge consequences.

Ashley HayThe writing is clear and lyrical. Some passages achieve a subtle beauty, but often they become too explicit. A final sentence robs a paragraph of its power by straightening out the image’s ambiguities rather than letting the reader linger over the possibilities. As with Hay’s previous book, The Railwayman’s Wife (2013), a poem embedded in the text is the focal point; here, from Michael Ondaatje: ‘For his first forty days a child / Is given dreams of previous lives. / Journeys, winding paths, / A hundred small lessons / And then the past is erased.’ The eponymous poem becomes the pretext for an argument between Ben and Lucy. The fight holds all of the book’s ideas – memory, parenthood, identity, place – and the action is pacey, but the poem compels the reader to stop and linger, to bring the idea of porous borders into the sentences. Hay employs powerful ideas; for example, that small instinctive actions have huge consequences.

‘I want to see, Mum. I want to know what’s there.’

They were the only words Elsie heard, and she over-my-dead-bodied them at once. And Lainey slipped away, leaving Elsie, scared and beset in her own kitchen. Afraid for the world and her daughter all at once. Send her a small, quiet world and keep her safe. As close to a prayer as she might get.

It is not the world that is dangerous, but Elsie’s desire to protect Elaine. The line between intention and effect is traversed without fanfare, and some ideas float away like the tidal river that borders the characters’ world. There is no defin-itive moment; instead, ideas are layered, one small action at a time, until the whole is revealed. Only then can we see the intricacy of the story, in which the river’s flowing quality is present within each sentence, the moods and tides reflective of the transformative power of parenthood.

Comments powered by CComment