- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

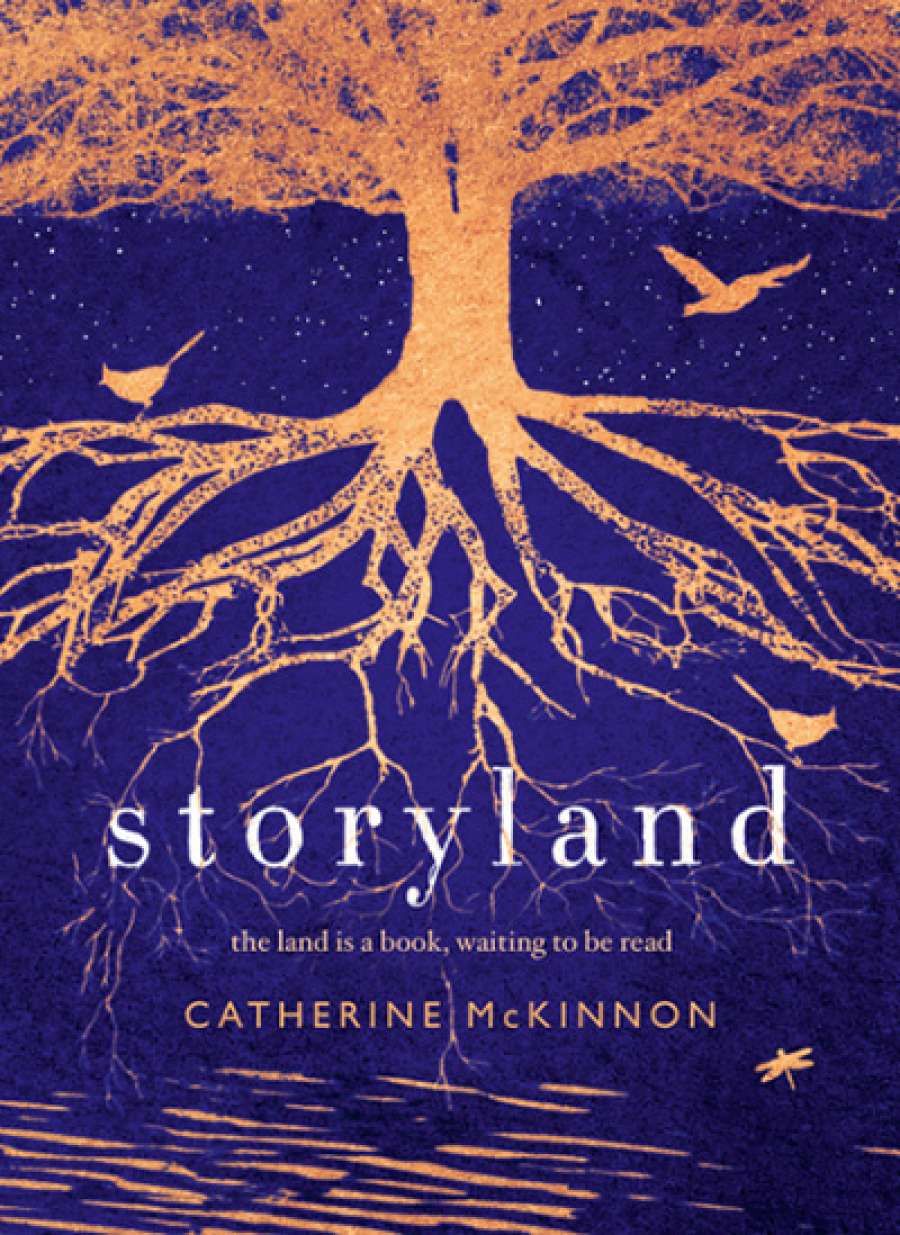

- Custom Article Title: Doug Wallen reviews 'Storyland' by Catherine McKinnon

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘I write best from place,’ Catherine McKinnon told Fairfax newspapers in a recent interview. Her second novel, which concerns centuries of human interaction with the New South Wales coast region between Wollongong and Lake Illawarra, makes this abundantly clear ...

- Book 1 Title: Storyland

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate $27.99 pb, 400 pp, 9781460752326

Founded on McKinnon’s obvious passion for research, the book entwines real history with her own imaginings. Storyland opens with narrator Will Martin, the fifteen-year-old cabin boy aboard Matthew Flinders and George Bass’s exploratory sailboat Tom Thumb in 1796. McKinnon sets the scene with atmospheric language but also records details from the expeditions: Flinders cannot swim, and all three men fear that the local Aborigines might be cannibals. Without glossing over their follies, McKinnon presents these historical figures as multifaceted people lodged in – and limited by – the prejudices of their time.

From there we move on to Hawker, an alcoholic former convict in 1822 who is haunted yet ruthless. Again, the character is based on a historical account, though only loosely. Next it is 1900: a young woman named Lola is running a dairy farm with her siblings while repressing the trauma of her lost baby and its conception. When tragedy strikes a neighbour, she is reminded of the suppression and physical danger that women must endure. Then, in 1998, the idiosyncratic ten-year-old Bel is thrust into close encounters with savage violence and the region’s Aboriginal history – two of the book’s recurring themes.

This quartet of scenarios can be difficult to connect with until we revisit them later. Initially, it is unclear why we are being told these stories, aside from the author’s own interest in local history, and we don’t spend enough time with each set of characters to truly connect with them on the first visitation. A few of the period trappings feel clichéd at first, like the Chinese character in Lola’s section, but they are increasingly fleshed out. The scenarios themselves make more sense when they have all been completed, even if McKinnon leaves each one unresolved to some degree.

The book’s centrepiece is a single section where a woman named Nada recounts her quest to escape murderous looters in the year 2033 after a storm has submerged Port Kembla and cut off the virus-stricken area from the outside world. This section shares a humane, ground-level detailing of post-apocalyptic survival with David Mitchell’s The Bone Clocks (2014) and Mark Smith’s The Road to Winter (2016), and it is here that McKinnon underscores the book’s environmental message, depicting a degraded land that is increasingly uninhabitable for its abusers. ‘We’ve always felt at peace at this place,’ says one character by way of reassurance, while another doubts whether this sense of sanctuary can continue.

It is this middle section that provides the book’s title, thanks to a project functioning like the narrative equivalent of a seed bank. In the face of a starkly altered planet, such oral history collects cautionary advice from mankind’s fraught past in the hope that humans might change their ways. One character hints at how this kind of perennial adaptability has sustained the human race despite itself: ‘Our concept of what is real is always changing.’

The reader must remain adaptive too in order to follow each new setting and time period in the book. McKinnon does merge the end and start of each section with a device grounded in the natural world, and certain characters and artefacts carry over between sections to bridge the distinct time periods. She also provides two maps at the back of the book, including Aboriginal and colonial place names.

Storyland does more than trace the impact of Western civilisation on this particular stretch of land: The book shows us how settlers have treated Aborigines, other majorities, and the land itself. Beyond the reverberating actions of individuals, we witness ancient rock formations and waterways transformed overnight by man-made climate change.

Catherine McKinnonMcKinnon, a playwright, theatre director, and senior lecturer at the University of Wollongong, has written an imperfect but deeply invested variation on Australian historical fiction. The landscape looms large in every section, and there is a pronounced resonance when she highlights human violence. The lack of resolution can leave the sections feeling more like loosely linked stories than a fully realised novel, but the individual sections still offer valuable insights. While McKinnon attempts to press home the power of storytelling too bluntly at the end, the book has undeniable cumulative power.

Catherine McKinnonMcKinnon, a playwright, theatre director, and senior lecturer at the University of Wollongong, has written an imperfect but deeply invested variation on Australian historical fiction. The landscape looms large in every section, and there is a pronounced resonance when she highlights human violence. The lack of resolution can leave the sections feeling more like loosely linked stories than a fully realised novel, but the individual sections still offer valuable insights. While McKinnon attempts to press home the power of storytelling too bluntly at the end, the book has undeniable cumulative power.

English native Will Martin may start out calling Australia an ‘upturn of the natural world’ for all its foreign elements, but he eventually sees a profound positive side to that distinction. ‘This land is a forever land,’ he muses. ‘Here, the clock ticks to a different time.’

Comments powered by CComment