- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

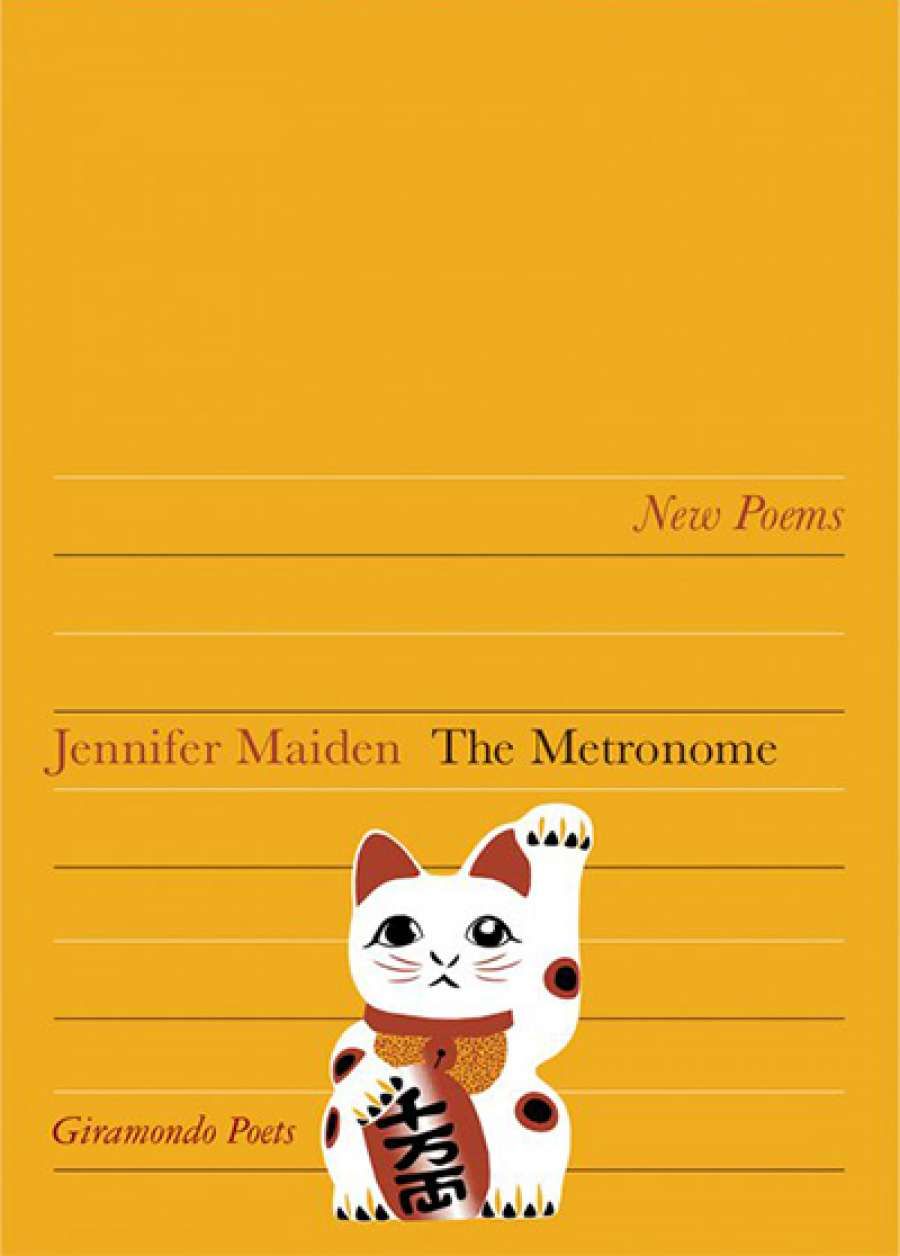

- Custom Article Title: Jill Jones reviews 'The Metronome' by Jennifer Maiden

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Jennifer Maiden’s latest book, The Metronome, is essentially part of a series that could be dated to the appearance of Friendly Fire in 2005 ...

- Book 1 Title: The Metronome

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo $24 pb, 96 pp, 9781925336214

Maiden’s poems, in this book as in her others, are unsentimental, as they inhabit our media-shaped, seemingly ordinary or evil, ‘wild or gentle’, obviously complex world that we would know and feel as real. Therefore, one of the things I have always appreciated in her work is that she is intensely interested in the way things work in the world – all kinds of things including politics, phones, and poetry. It is a kind of realism that not only recognises that the way things work actually matters, but that the details of this matter. Thus: ‘His / own “Love you” bounced back with a speed / and lack of echo only CIA technology / could probably have provided ...’ In other words, one of Maiden’s characters in this poem, George Jeffreys, ironically recognises that his phone is being bugged.

I am particularly glad that Maiden has space for birds in her work. Some grumpy reviewers have taken poets to task for including birds in poems. Possibly it is a set against some assumed gesture to an outdated ‘pastoral’. Goodness. Australian urban places teem with birds. I have had offices on major roads in two cities for many years, and there are always the ubiquitous lorikeets around, let alone everything from kookaburras to high-flying pelicans and the odd raptor. And there are other places such as the less-than-pastoral Nauru, the setting for Maiden’s moving poem ‘Clare and Nauru’, containing the reference to the phone mentioned above, wherein she mentions the Nauru Reed Warbler, which warbles in ‘a long fine treble’ and is, according to her character Clare Collins, ‘the only / native species the locals don’t eat’. I don’t take this bird in the poem as a symbol, or only a symbol – it is as real a bird as a writer can make. It survives as itself as well as a figure.

As for the poetry, Maiden draws attention, as I have suggested, to how poetry works, among many other things – ‘... Binary metre belongs / to life’s basic history, alone / reassuring continuity ...’ – and her books are particular in their forms though a casual observer – and I have heard this said – may feel that they seem or look ‘the same’, or, the poems seem ‘to sprawl’. Maiden’s attention to form is, however, neither casual nor unpremeditated nor technically loose. Her use of enjambment is key to making the poems, particularly the longer dialogic or narrative poems, turn (literally) in a way that keeps the flow and tension uppermost. Although not strictly metrical, they tend to four- or five-stress (or beat) lines with, obviously, more than a hint of pentameter or tetrameter. This allows these poems to move easily, for the reader, through their complex conversational manoeuvres.

Jennifer Maiden (photograph courtesy of Giramondo Publishing)

Jennifer Maiden (photograph courtesy of Giramondo Publishing)

Maiden also uses rhyme effortlessly in a number of ways. There is the book’s title poem, ‘Metronome’, with its mix of perfect and slant rhyme, and even some sight rhyme. Given it is the first poem in a book called The Metronome, it is significant that it adopts a sound structure that mimics, to an extent, the metronome it speaks of. Another poem, ‘Diary Poem: Uses of Catalonia’, moves in and out of rhyme, at times using single, often double, often slant or identical rhyme. But the rhymed line endings do not thud or become predictable. These are poems that turn on their sonic effects, their lineation, their movement within language.

I have not said much that is specific about the ‘aboutness’ of the poems. Enough reviewers, including myself in a previous review, have noted and explicated Maiden’s ongoing political and cultural concerns. Not that this book is a repetition of those. As Gertrude Stein would say, there is no such thing as repetition, rather there is insistence. Everything changes; Maiden knows this and shows this. She does so, however, through complex yet engaging poetry structures and rhythms. She is ever the masterful technician as much as a poet of intelligence, wit, integrity, and the senses.

Comments powered by CComment