- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Jan McGuinness reviews 'A Writing Life: Helen Garner and her work' by Bernadette Brennan

- Custom Highlight Text:

Who is the I in Helen Garner’s work? This is the question Bernadette Brennan probes by canvassing more than forty years of Garner’s writing and her seventy-four-year existence ...

- Book 1 Title: A Writing Life

- Book 1 Subtitle: Helen Garner and her work

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 334 pp, 9781925498035

Brennan relies chiefly on an examination of published works, letters, and diaries, the thoughts of a few significant players, including Garner’s long-time publisher Hilary McPhee, and conversations with Garner herself. The result is a literary portrait of a writer who has suffered for her art. Don’t they all! But Garner seems particularly susceptible. She is the sort of writer who writes to understand herself and what she thinks. Possibly this is because she learned to be self-questioning from a young age.

Garner’s first clash was with her father. Born in Geelong in November 1942 to Gwen and Bruce Ford, she is the eldest of their six children of five daughters and one son. She escaped the chaos of family life by losing herself in books, a point of contention met with admonishments to ‘go outside’ and ‘get your nose out of that book’. Parental responses of anger and dismissal were, according to Garner, the chorus of her childhood. Bruce was a wool merchant who had never read a book, a ‘vivid, obstreperous character’, an ‘impatient, rivalrous, scornful’ man who dominated his timid, depressive wife and bullied his children, as described by Garner in ‘Dreams of Her True Self’ from her latest book of essays, Everywhere I Look (2016). Her extended battle with him has been one of the defining features of Garner’s adult life, and a central drama of her writing, writes Brennan.

Enrolment in Arts at the University of Melbourne in 1961 spelt freedom, new friends from vastly different backgrounds (Axel Clark, son of Manning first among them), and further disquiet over what she now views as self-destructive, youthful behaviour, including her poor academic showing. At The Hermitage in Geelong, Helen was dux and head prefect. Brennan describes it as a prestigious (a word used also to describe McPhee Gribble Publishing and Ormond College) school for girls. University was a rude awakening for Garner. She proved a desultory student and emerged with a third class degree, the experience creating a lasting unease with academia and institutional authority that, Brennan suggests, influenced her handling of The First Stone (1995).

Tim Winton and Helen Garner at the 1986 Adelaide Arts Festival

Tim Winton and Helen Garner at the 1986 Adelaide Arts Festival

(photograph by Cathryn Tremain/Fairfax Images, first published in The Age, 10 May 1986, from the book under review)

A post-graduation altercation with her father, who now viewed her as an immoral radical, created a break lasting many years; he even vetoed contact with other family members. This drove Garner into the cheap and cheerful Melbourne inner city share-house scene of the late 1960s. There she immersed herself in a different style of family life based on friendship and shared counter-culture values, taught at school, married actor and academic Bill Garner, gave birth to her daughter, Alice, and within three years was on her own again. The first of her three marriages seems to have foundered amid the creative, sexually free, but weirdly controlling and all-consuming allure of the Carlton-based Australian Performing Group (APG) of actors and playwrights in which Bill Garner immersed himself.

Nevertheless, it was as a member of the APG’s women’s collective that Garner developed her writing chops, working on an experimental feminist theatre piece called Betty Can Jump. It played to packed houses (of mostly wildly enthusiastic women) for seven weeks in late 1971, caused upset among the male-dominated APG, and coincided with the end of her marriage. The production and the audience’s response helped to shape Garner’s early writing, says Brennan.

Through the ensuing weeks of performances, she learned about the capacity of diary entries to capture mood and experience. She discovered that brevity and structure were powerful tools of communication. Garner also appreciated the need for women to record their experiences or risk remaining forever silenced ... the APG strove to produce Australian theatre true to the Australian vernacular, accents and experience. Garner does something similar in her writing.

Garner’s teaching career ended in controversy over her forthright responses to questions about sex raised by her Year Seven Fitzroy High School students. She was already writing features, book and film reviews for the radical paper Digger, in which the issue was aired. Sacked by the Education Department, she survived for a while on benefits with help from Bill Garner and her parents, and began shaping her diary into what she thought might become a novel. The result was Monkey Grip, published in September 1977.

Based on her own experience of being trapped in an addictive love affair with a heroin addict and set around Carlton and Fitzroy, the book aroused interest and sold well, though critics were divided as to whether it was ‘tremendous’ and ‘truthful’ or ‘immoral’ and ‘sordid’, depending on their own social attitudes. The main point of contention, however, was that Garner had simply published her diaries. This accusation has dogged her fiction ever since. Now that she is even better known for her non-fiction renderings of morally complex and controversial issues and crimes (The First Stone, Joe Cinque’s Consolation [2004], This House of Grief [2014]), it has spilled over into what critics claim is her egocentric placing of self at the centre. In so far as novels and short stories are concerned, such criticism ignores the creative process of shaping and crafting story, Garner’s muscular use of language and evocative imagery. It also ignores how and why diarised entries contribute to a novel’s meaning says Brennan. Quoting Anaïs Nin, she highlights how they record what is strongly felt in the moment and thus reveal ‘the power of recreation to lie in the sensibilities’.

Helen GarnerAs for the non-fiction books, following Brennan into the labyrinth of anguish and uncertainty Garner suffers over them makes for remorseless reading. Accusations of bias, feminist revisionism, and the controversy, debate, and unrelenting publicity that followed publication of The First Stone fed into the breakdown of Garner’s marriage to fellow novelist Murray Bail and led to depression, a period of analysis, and refuge in religion. A ‘persistent, aching, leaking sadness’ weighed on her during the seven years it took to finally convict Robert Farquharson of drowning his three sons, his trials and appeals being the subject of This House of Grief. Critic James Ley judged it the best of Garner’s three non-fiction books, saying that she ‘has perfected a kind of negative capability in which she acts as a focal point for the book’s themes, which are channelled through her reactions but resonate far beyond them’.

Helen GarnerAs for the non-fiction books, following Brennan into the labyrinth of anguish and uncertainty Garner suffers over them makes for remorseless reading. Accusations of bias, feminist revisionism, and the controversy, debate, and unrelenting publicity that followed publication of The First Stone fed into the breakdown of Garner’s marriage to fellow novelist Murray Bail and led to depression, a period of analysis, and refuge in religion. A ‘persistent, aching, leaking sadness’ weighed on her during the seven years it took to finally convict Robert Farquharson of drowning his three sons, his trials and appeals being the subject of This House of Grief. Critic James Ley judged it the best of Garner’s three non-fiction books, saying that she ‘has perfected a kind of negative capability in which she acts as a focal point for the book’s themes, which are channelled through her reactions but resonate far beyond them’.

According to Brennan, Garner’s front and fall-back position is that of the observer who wrestles and agonises over all before her, but whose ponderings and conclusions are informed by a tsunami of research, reading, interviewing, and anguishing over questions of morality, personal responsibility, style and voice, and the profound and often unpleasant examination of her own reactions. The craft lies in her ability to weave it all into a compelling narrative while maintaining the stance of the personally immersed, questing everyman. The ‘me’ character, she admits, is in all her work and is a carefully constructed self.

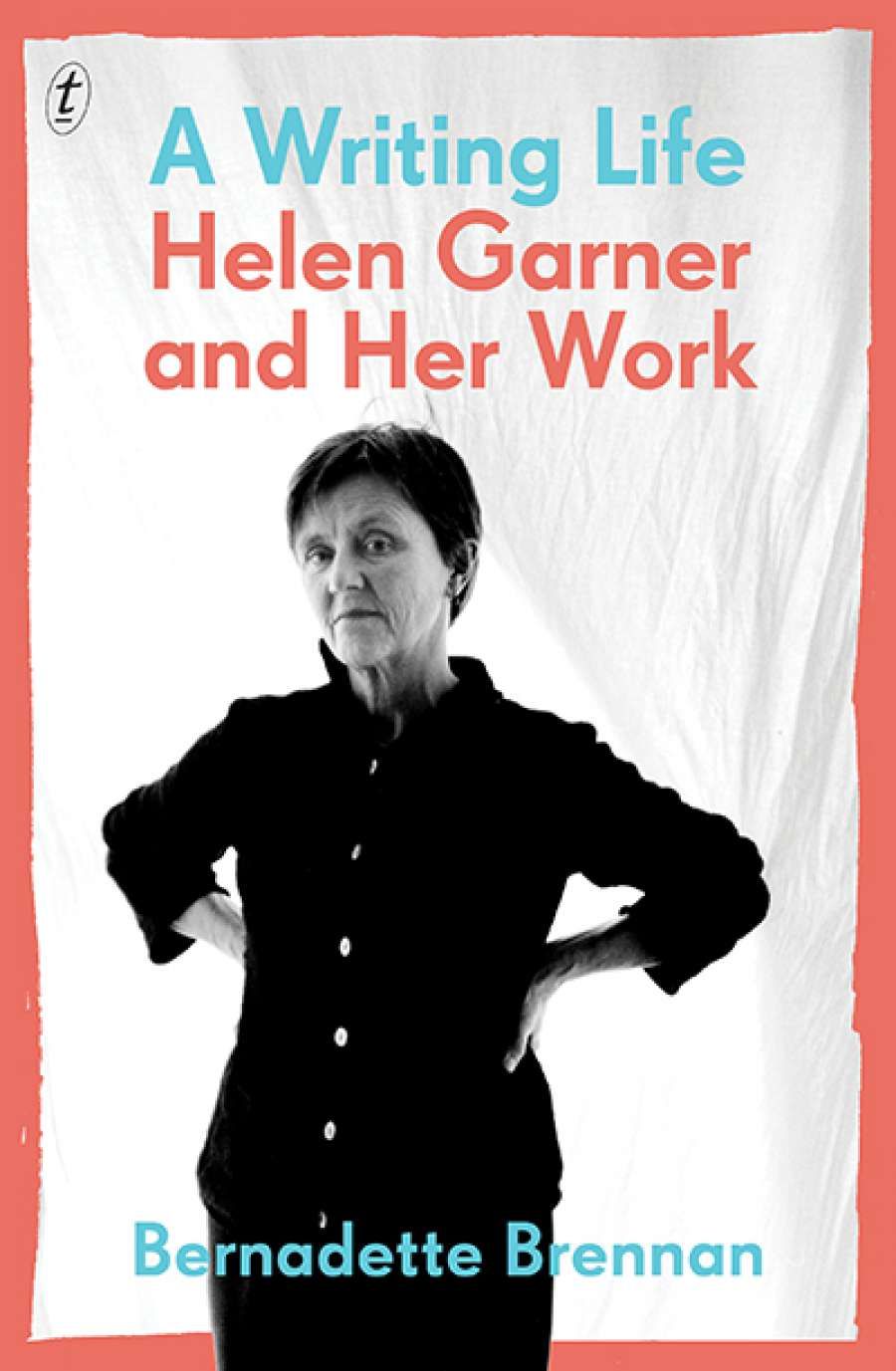

Garner puts her real self out there. Her writing invites controversy and confrontation, but also applause and acclaim. Despite her evident vulnerability and the personal cost of her writings, one is left with a sense that Garner thrives on the whole package. Consider the stern, assertive hands-on-hips front-cover image of Brennan’s book. Garner’s expression is apprehensive, defensive, bring-it-on. Is she still alert to that chorus of anger and dismissal, wondering what fresh hell awaits her, or is she asking, given so much formative disapproval, ‘Am I there yet?’

Comments powered by CComment