- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

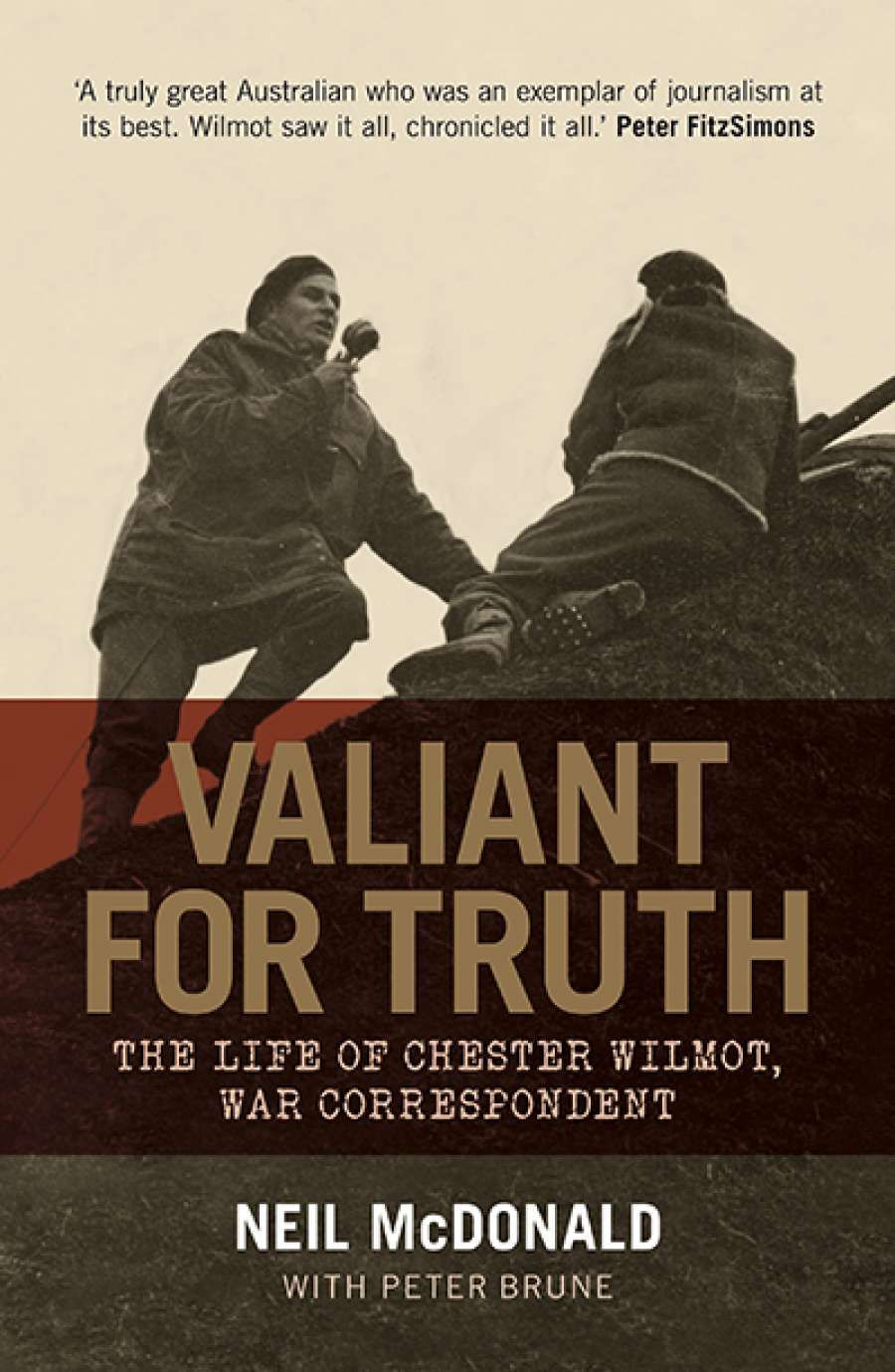

- Custom Article Title: Kevin Foster review 'Valiant For Truth: The life of Chester Wilmot, war correspondent' by Neil McDonald with Peter Brune

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Valiant For Truth

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of Chester Wilmot, war correspondent

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth $49.99 hb, 500 pp, 9781742235172

For all its thoroughness, this is as much an exercise in advocacy as it is a work of appraisal. Wilmot emerges from the book as both establishment superman and empathetic everyman. The son of a prominent journalist, he was Melbourne Grammar School Captain and an Arts/Law graduate from the University. In his younger years, Neil McDonald insists, Wilmot was also a committed socialist and the faithful friend of the common man. Not that Wilmot saw much of him. Wilmot was a serial cosier-up to authority, both scion and creature of the establishment. The trusted confidant of men of letters, men of arms, and men of power, Wilmot met and mixed with generals and statesmen as an equal – a big man among big men. His overweening arrogance was almost his undoing.

A witness to and interpreter of history, Wilmot was increasingly convinced that he had the right, and the credentials, to play a more active role in shaping its outcomes. He was a faithful servant of authority when it served his interests, but when it did not he was ready to pick sides and cloak his advocacy in the guise of reporting. When he was caught in the act, confounded in or punished for his scheming, he shamelessly portrayed himself as a martyr to journalistic freedom.

Wilmot’s character flaws were writ large in his legendary run-in with Thomas Blamey, who divided more opinion than he ever commanded. While McDonald’s treatment of these events covers much familiar, highly partisan ground, it also illuminates some pertinent but neglected questions about the legitimacy and limits of press freedom in wartime. While Blamey’s insistence that the media should offer no criticism of the Australian Army in the field was unreasonably extreme (if still popular in some quarters in today’s ADF), Wilmot’s conviction that the freedom of the press not only licensed reasonable censure but also the liberty to advocate on behalf of one military faction or another is no less extreme. It was both naïve and arrogant of Wilmot to believe that, with the assistance and at the behest of disgruntled senior officers, he could play Brutus to Blamey’s Caesar and help bring down the nation’s supreme military officer.

Chester Wilmot (photograph by Athol Smith via Wikimedia Commons)It was rich for Wilmot to portray himself as a martyr to journalism’s highest principles when in his own naked partisanship and his readiness to cloak factional loyalty as objective appraisal, he consistently breached so many of its core tenets. Wilmot’s treatment by Blamey exposed serious shortcomings in the military command’s tolerance of and readiness to accommodate reasonable criticism. It is not the role of a free press to slavishly support the military regardless of objective considerations. However, it also reinforced some inescapable truths about where the power lies at moments of acute national crisis, the proper bounds of reasonable media criticism and the role of the reporter in such a context. Blamey may have been, in General MacArthur’s judgment, a ‘sensual, slothful and doubtful character’, but he was also ‘a tough commander’ and ‘the best of the local bunch’. Crucially, Curtin recognised him as the right man for the job at hand and continued to support him.

Chester Wilmot (photograph by Athol Smith via Wikimedia Commons)It was rich for Wilmot to portray himself as a martyr to journalism’s highest principles when in his own naked partisanship and his readiness to cloak factional loyalty as objective appraisal, he consistently breached so many of its core tenets. Wilmot’s treatment by Blamey exposed serious shortcomings in the military command’s tolerance of and readiness to accommodate reasonable criticism. It is not the role of a free press to slavishly support the military regardless of objective considerations. However, it also reinforced some inescapable truths about where the power lies at moments of acute national crisis, the proper bounds of reasonable media criticism and the role of the reporter in such a context. Blamey may have been, in General MacArthur’s judgment, a ‘sensual, slothful and doubtful character’, but he was also ‘a tough commander’ and ‘the best of the local bunch’. Crucially, Curtin recognised him as the right man for the job at hand and continued to support him.

Ivone Kirkpatrick famously noted that during World War II the BBC set out to give the public ‘the truth, nothing but the truth and as near as possible the whole truth’. Wilmot was, of course, a key player in delivering on this ambivalent promise of fullish disclosure, and at his best he was a credit to his employers and the great cause they served. That he was not always at his best in managing his relations with the military, nor a paragon of selfless reporting, are important personal and professional failings that the book might have considered in greater detail and thereby rendered a more rounded portrait of a contradictory and compelling figure.

Comments powered by CComment