- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

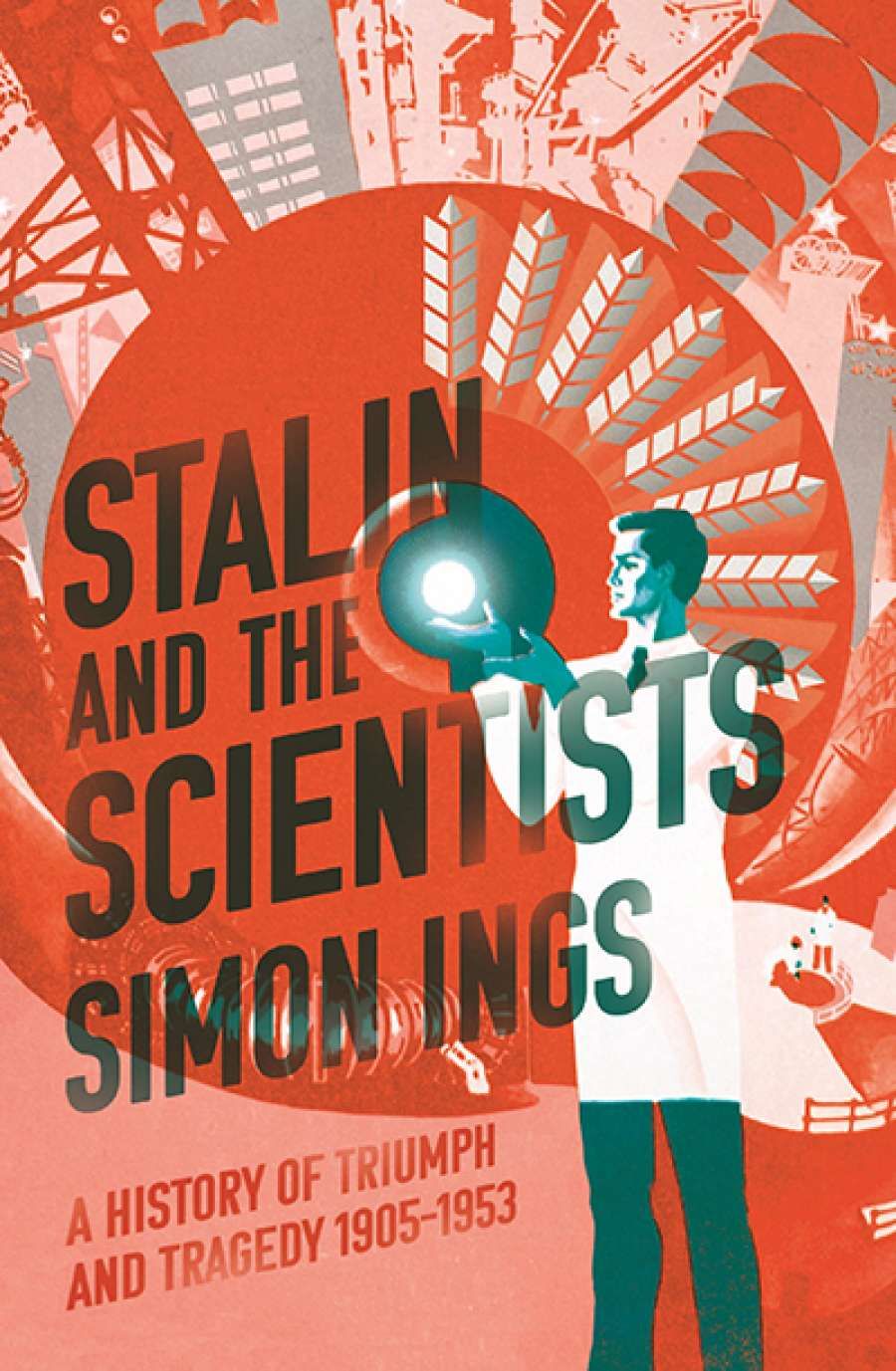

- Custom Article Title: Mark Edele reviews 'Stalin and the Scientists: A History of triumph and tragedy 1905–1953' by Simon Ings

- Book 1 Title: Stalin and the Scientists

- Book 1 Subtitle: A History of Triumph and Tragedy 1905–1953

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber & Faber $49.99 hb, 527 pp, 9780571290079

If the Lysenko affair showed the destructive effects of politicians meddling in science, physics under Stalin exemplified the other extreme. Lavish funding, privileged living conditions, excellent research environments, and the freedom to explore any theory, ‘idealist’ or not, led to physics reaching world standard. The reason for this government largesse, of course, was the atomic bomb, which Stalin needed in order to retain the superpower status the Red Army had won for him in the Second World War. Leave the scientists alone, the dictator ordered his underlings – ‘we can always shoot them later.’ As a result, the Soviet Union got not only the atomic bomb, but also a crop of dissidents used to thinking on their own, most prominently Andrei Sakharov. This story has been told in detail by David Holloway in his path-breaking Stalin and the Bomb (1994).

Stalin and the Scientists adds little to this well-established narrative. The book is largely based on English-language secondary sources. Ings, a science writer and novelist, has not been to the archives to discover new sources on the behind-the-scenes machinations of scientists and politicians during the Stalin years.

What can we learn from his narrative? Quite a lot, argues Ings. ‘We are all little Stalinists now,’ he writes. We are ‘convinced of the efficacy of science to bail us out of any and every crisis, regardless of what science can actually do, impatient of anything scientists might actually say’. As an interpretation of our own predicament, this statement seems wide of the mark. Today, aggressive campaigns are fought on the basis of established scientific conclusions, but with the goal of limiting the destructive consequences of our own actions. One could mention here the attempts to restrain the use of antibiotics to slow the further development of superbugs or to check global warming by concerted international action. Among believers in science, only a minority advocates muddling through on the assumption that our ingenuity will eventually save us. The problem is not ‘Stalinist’ naïveté, but growing anti-science denial that anything might indeed be wrong, or a cynical after-me-the-deluge-as-long-as-profits-are-right mentality.

T D Lysenko speaking at the Kremlin in 1935. At the back (left to right) are Stanislav Kosior, Anastas Mikoyan, Andrei Andreev and the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin (Soyfer, V N, The State and Science, Hermitage, 1989 via Wikimedia Commons)

T D Lysenko speaking at the Kremlin in 1935. At the back (left to right) are Stanislav Kosior, Anastas Mikoyan, Andrei Andreev and the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin (Soyfer, V N, The State and Science, Hermitage, 1989 via Wikimedia Commons)

As a popular history of Stalinist science, Ings’s book fails on another level. The general historical context is laid out so shakily that non-specialists will be easily misled. Readers could be excused if they come away with the notion that the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–5 began with the Battle of Tsushima in 1905 and that this battle led to the revolution of 1905; that the 1921–22 famine started in 1922; that Stalin ‘ousted’ Lenin in 1922 and henceforth was pulling the strings of Soviet politics, implementing his master plan; that the great famine of 1932–33 preceded dekulakisation; or that the Soviets occupied all of Finland in early 1940. The narrative of Stalin’s rise is imprecise, to say the least. The recurrent claim that Russia, ever since Peter the Great, had lacked ‘any civic life worth the name’ runs counter to a little library of books on the late Romanov empire, handily summarised in Wayne Dowler’s admirable Russia in 1913 (2010).

Stalin and the Scientists, then, cannot be recommended. Readers are better served with the classics mentioned above or the excellent wider studies which emerged after the Soviet archives were opened: Nikolai Krementsov’s Stalinist Science (1997), Alexei Kojevnikov’s Stalin’s Great Science (2004), or Ethan Pollock’s Stalin and the Soviet Science Wars (2006). Graham’s What Have We Learned About Science and Technology from the Russian Experience? (1998) answers the ‘so what?’ question much better than Ings’s long-winded narrative.

Comments powered by CComment