- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

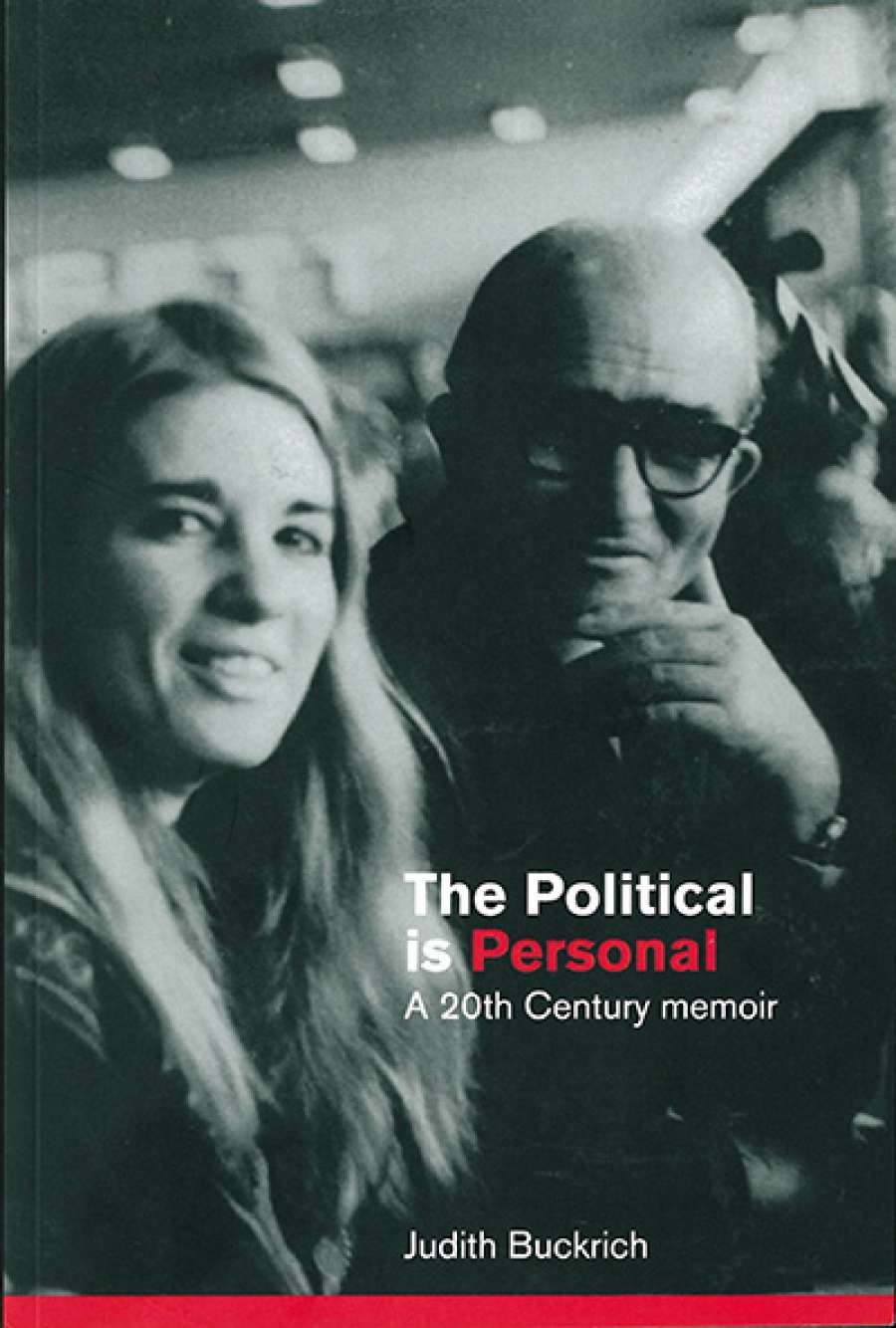

- Custom Article Title: Suzy Freeman-Greene reviews 'The Political is Personal: A 20th century memoir' by Judith Buckrich

- Book 1 Title: The Political is Personal

- Book 1 Subtitle: A 20th century memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Lauranton Books $30 pb, 420 pp, 9780994250728

Buckrich has had a peripatetic life, writing plays, journalism, and non-fiction books; teaching and translating. She has lived in Budapest, Chicago, and, mostly, Melbourne. Her Hungarian-born father, Anti, emigrated to the United States in 1929 and became a communist. He returned to Hungary in 1948, after advertising for a wife. Her mother, Erika, who answered the ad, was a young Jewish survivor of Auschwitz and Ravensbrück. The two married, had Judith in 1950, and moved to Melbourne when she was eight.

Their first year in Australia was ‘terrible’. Erika left Anti for another man. (They later reconciled, but the marriage was unhappy.) Judith, who spoke no English, was punished at school for not knowing the answers to questions. Throughout her childhood, Anti drank too much. ‘I was very young, probably only three-years-old,’ she reports, ‘when I first stepped in front of Erika to stop Dad from hitting her in a drunken rage.’ As Judith grew into an exuberant young woman, she increasingly lived a double life, especially after Anti slapped her during an argument.

Buckrich tells us she never really knew her father. Nor, unfortunately, does the reader get much of a sense of him. The first section of the book, outlining her parents’ stories, is strangely unmoving. Part of the problem is that it lacks their voices. We read, for instance, of a postcard Anti sent to his sister, but there are no direct quotes from it. Later, we are told, ‘my mother says that I was a sweet little girl’. Clearly, Buckrich has interviewed Erika, so why don’t we hear more from her? Instead, the author rushes from one event to another. Potentially poignant scenes are not fleshed out.

Buckrich’s brisk, confessional tone works better when depicting her own adventures in the 1970s and 1980s. Things pick up for the reader when she moves to Chicago in 1971 to stay with her cousin. Her portrait here of a trusting young woman from suburban Melbourne thrust into Chicago’s Near North Side is compelling. The pair live near a tavern where gunshots are sometimes heard. She goes swimming in Lake Michigan: it contains dead fish and broken glass. She is scared all the time. There is a dreadful account of Buckrich learning that her cousin has been raped.

Back in Melbourne, Buckrich studies drama and media studies at Rusden State College and helps organise public consciousness-raising sessions called ‘Sexuality and Ourselves’. A feminist who finds monogamy overrated, she plunges into new liaisons, jobs, households, creative projects, and political activities. In contrast to her father’s generation, she writes, ‘we considered our enjoyment part of changing the world’. I enjoyed the glimpses of 1970s counter-cultural life here: from Gembrook hippies in their ‘dull brown jumpers of raw wool’ to the image of Buckrich and the pale, thin writer–musician Sam Sejavka (another lover), wandering naked on the beach at Koo Wee Rup.

In 1978, Anti dies. Buckrich describes learning of her father’s death, and farewelling his body, in one paragraph. (‘His jaw had been tied closed, and he was very white and cold.’) For the amateur psychologist, the most memorable aspect of this account is the photo she has chosen to place beside it in the book. It is an image of Buckrich that was projected on a screen in her first show at Carlton’s La Mama Theatre, the following year. She is naked, save for a pair of silver, knee-high boots and a silver strap criss-crossing her torso.

After a lively section on her return to Budapest and a segue into the writing of her books (mostly local histories and the biography of a science fiction writer), The Political Is Personal peters out with an account of Buckrich’s recent travels as chair of the PEN Inter-national Women Writers’ Committee. It is disappointing that the memoir of someone who advocated so vigorously on the part of authors is so uneven. It could have used a tough editor: someone to urge Buckrich to play around with the linear narrative, more fully describe key moments, and axe the chapters on her holidays. Still, Buckrich’s intimate, unsentimental voice is appealing. There is something bracing about her company when she’s living at full tilt.

Comments powered by CComment