- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Alison Broinowski reviews 'Subtle Moments: Scenes on a life’s journey' by Bruce Grant

- Book 1 Title: Subtle Moments

- Book 1 Subtitle: Scenes on a life’s journey

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing $34.95 pb, 448 pp, 9781925495355

In the 1980s the trope of young Australia exchanging its British mentor for an American one was already outdated. Later generations of Australian writers, some with Asian languages, and some born in Asian countries, were unconcerned about Asian inscrutability, the innocence and ignorance of Australians, or Australia’s claim to superior morality. By 1994, older men with Asian brides were satirised in Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, and by the 2000s readers had acquired a taste for Ouyang Yu’s acerbic double-takes on Australia and China.

A former journalist, foreign correspondent, diplomat, academic, and prolific writer of fact and fiction, Grant, now ninety-two, selects fourteen ‘scenes’ from his life. The first displays his rural childhood in Western Australia, then at selective-entry Perth Modern School. Service in the army and navy produce a novel about his experiences in Darwin. Meeting people who will later be helpful to him, including Casey and Menzies, he studies Arts at Melbourne University, adding the Clarks, the Reeds, ‘Mac’ Ball, Christesen, Ryan, and Santamaria to his politically eclectic list of friends. Apart from ‘the Marxists’, Australians ‘knew little of Asia’, Grant recalls, perpetuating the common fallacy that because the people he knew were Asia-illiterate, so was everyone else.

Grant’s scenes then become a semi-chronological slide-show. He writes for The Age, turns down a job offer at ASIO, and mentions in passing that he has a wife and three children. Next, he writes from London (with the family, but already having ‘personal difficulties’). In the early 1960s he is without them in Singapore, and also covering Indonesia, the subject of his first book, now a classic (Indonesia, 1964). A year at Harvard follows, then Washington. In another slide, Grant meets Joan Pennell in New York in 1959, where she works for Radio Free Europe; she eventually joins him in Melbourne and they have two sons. A prodigious worker, he teaches Australian foreign policy at Melbourne University while still contributing to papers in Australia and the United States.

Grant keeps in touch with Menzies but in 1972 he and sixteen others publicly call for a change of government, and Whitlam makes him high commissioner in New Delhi. After the Dismissal, he joins Citizens for Democracy in support of Whitlam. That brings his posting to an end, and he and Joan return to Melbourne. From 1988 he works with Gareth Evans on their magisterial book on Australia’s foreign relations (1991), establishes the Australia–Indonesia Institute, and chairs it. In 1989 Joan is teaching in China when Tiananmen happens, Grant travels in Cuba and the Balkans with the ‘frolicsome’ Indonesian-Australian journalist Ratih Hardjono. Their brief marriage ends in 1999, when she converts to Islam.

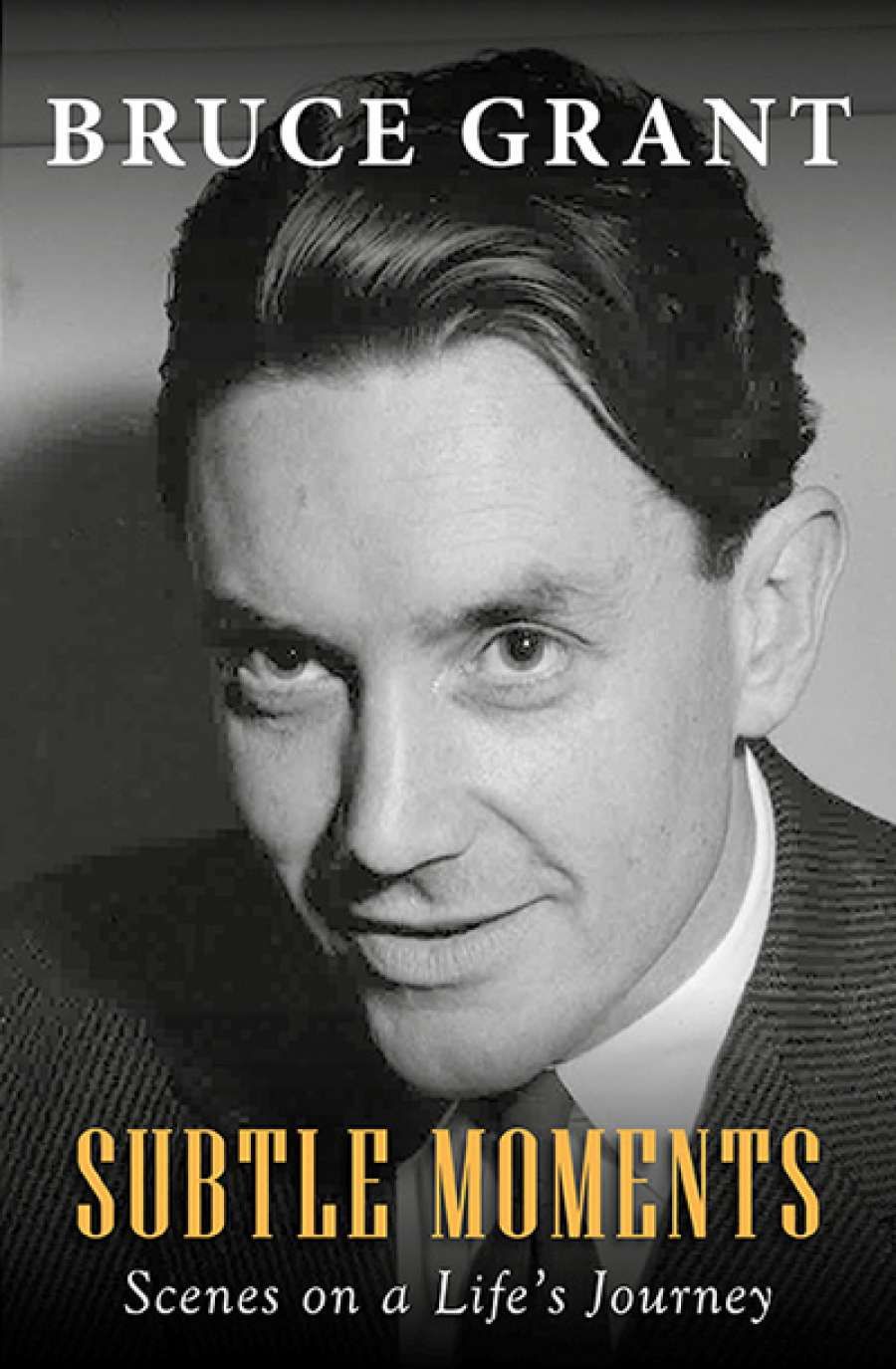

Bruce Grant (photograph by Richard Compton, Monash University Archives)Grant would agree with Goethe that an undocumented life is not worth living. He reproduces testimonial letters about himself from headmasters and professors, and letters of introduction from Casey and Menzies, as well as his own generous obituaries to friends, and Joan’s 1994 ultimatum letter. In a scene called ‘Trusty and Well-Beloved’, he even includes the queen’s letters of credence for his ambassadorial appointments in India, Nepal, and Bhutan, although as a republican he twice declines an ‘honour’. Adept as a fence-sitter, or as he puts it ‘a creature of a gradualist tradition’, Grant writes for both Meanjin and Quadrant. He wants Australia to take ‘independent’ initiatives in our region, but within the US alliance. He is scathing of the espionage and intelligence industry, but won’t blame the CIA for Whitlam’s dismissal. He works with Gareth Evans on eliminating nuclear weapons, but now Australian policy has changed he says the issue is ‘complex’. He names his trilogy after the Asian Century, but neither Kishore Mahbubani’s work nor the 2011 White Paper, Australia in the Asian Century, rate a mention.

Bruce Grant (photograph by Richard Compton, Monash University Archives)Grant would agree with Goethe that an undocumented life is not worth living. He reproduces testimonial letters about himself from headmasters and professors, and letters of introduction from Casey and Menzies, as well as his own generous obituaries to friends, and Joan’s 1994 ultimatum letter. In a scene called ‘Trusty and Well-Beloved’, he even includes the queen’s letters of credence for his ambassadorial appointments in India, Nepal, and Bhutan, although as a republican he twice declines an ‘honour’. Adept as a fence-sitter, or as he puts it ‘a creature of a gradualist tradition’, Grant writes for both Meanjin and Quadrant. He wants Australia to take ‘independent’ initiatives in our region, but within the US alliance. He is scathing of the espionage and intelligence industry, but won’t blame the CIA for Whitlam’s dismissal. He works with Gareth Evans on eliminating nuclear weapons, but now Australian policy has changed he says the issue is ‘complex’. He names his trilogy after the Asian Century, but neither Kishore Mahbubani’s work nor the 2011 White Paper, Australia in the Asian Century, rate a mention.

At the end, instead of writing more on North Asia or at least on contemporary Indonesia, Grant offers the surprising view that Australia in the UN Security Council was no longer seen as a British protégé or an American proxy, but a multicultural supporter of peace, international law, human rights, nuclear disarmament, public health, education, and women; active on climate change and against racial discrimination. Recently, he admits, he and his Melbourne friends decided ‘something was happening’ in Australian public life, although ‘no-one seemed sure what it was’.

Grant tried to resolve the Australian dilemma in his 1983 book of that name. He still hasn’t.

Comments powered by CComment