- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

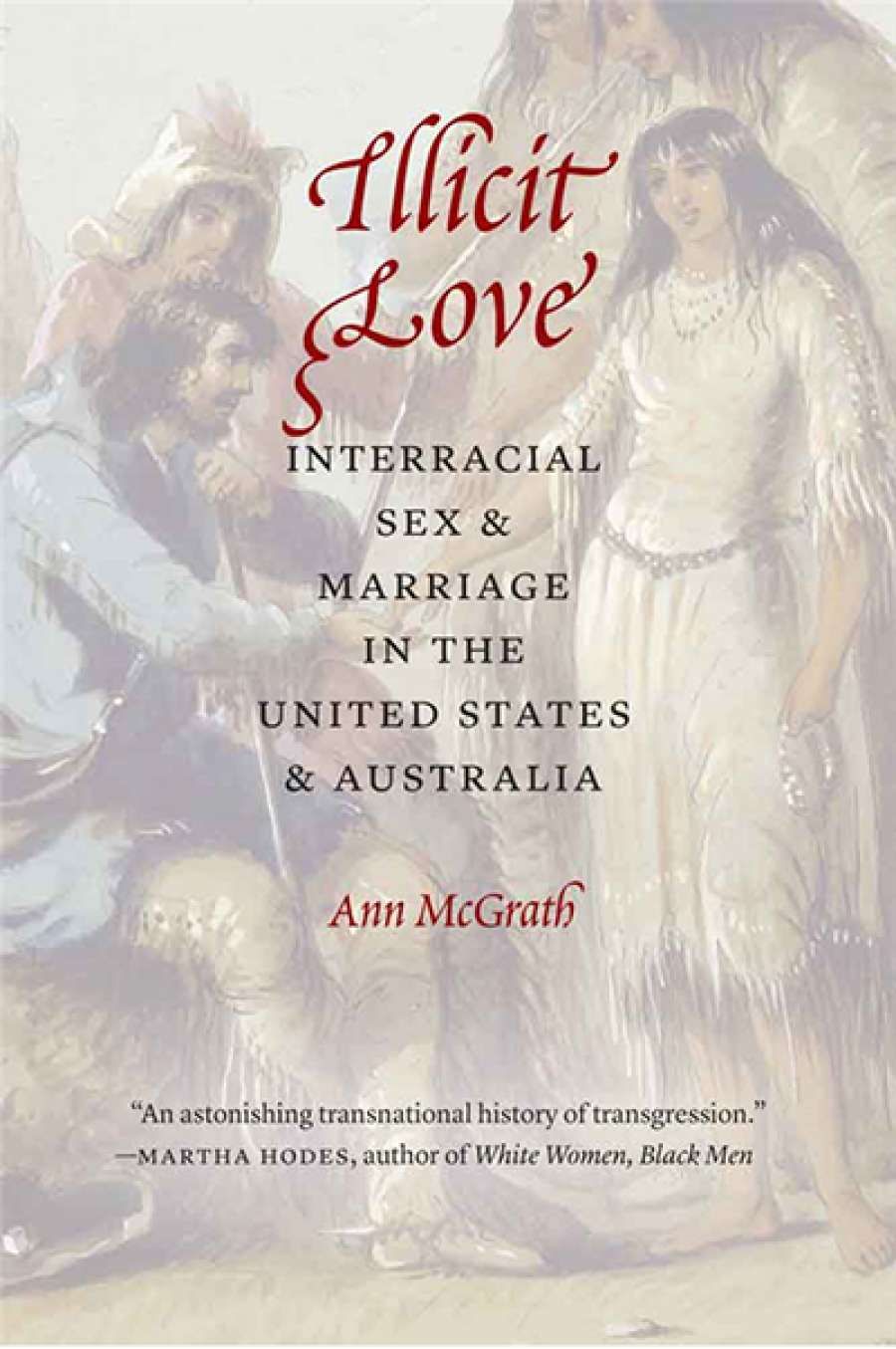

- Custom Article Title: Mark McKenna reviews 'Illicit Love: Interracial sex and marriage in the United States and Australia' by Ann McGrath

- Book 1 Title: Illicit Love

- Book 1 Subtitle: Interracial sex and marriage in the United States and Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Nebraska Press, $63 hb, 534 pp, 9780803238251

Illicit Love builds on McGrath’s expertise in the history of race relations in Australia, but adds another crucial dimension: the parallel history of those who dared to cross racial and national boundaries in the United States. As McGrath explains, ‘in histories of colonialism, the stories of marriages across colonizing boundaries’ have been ‘razed by a systemic forgetting’. Blurring the ‘dividing lines between Indigenous and settler-colonizer space’, these relationships revealed a countervailing history: Beneath the official tenets of racism espoused by governments, the law, police, and the wider community, countless men and women on the frontier refused to comply with the strictures placed on them. Instead, as McGrath asserts, they sought ‘control of their sexual partnerships and family arrangements’ as a ‘fundamental liberty’, and in the process they remade both the everyday fabric of their social relations and their nation’s destiny.

Illicit Love cuts against the grain of more familiar narratives of settler exploitation of Indigenous people – McGrath shows how Aboriginal women often entered willingly into monogamous and plural unions with white men – adroitly revealing that many of these same women ‘saw intermarriage from inside the world of their own complex system of laws and values’, integrating outsiders ‘into their own systems of family and ways of living in country’. McGrath’s transparent and engaging style (she incorporates the colour and drama of her search in the archives into her narrative, describing library interiors, manuscript presentation, and expressing her frustration when correspondence goes ‘missing’), combined with a chapter structure that shifts effortlessly from broader historical contextualisation to the more finely honed detail and personal drama inherent in the stories she has unearthed, constitute an accomplished example of contemporary historical scholarship. For McGrath, there is no conflict between scholarship and storytelling.

Harriett Gold ca. (Wikimedia Commons)One of the most telling aspects of the relationships that McGrath narrates in Illicit Love is the crowning hypocrisy of powerful men who, when faced with a choice between adherence to the principles of racial segregation they had advocated in public and satisfying their longing for intimacy, swiftly chose the latter course. McGrath tells the story of the Anglican missionary Ernest Gribble’s ‘illicit’ relationship with Jeannie, a Yarrabah woman with whom he fathered a child in 1908 during his tenure at Yarrabah Aboriginal Mission near Cairns. Gribble, who regularly preached that such unions were little more than ‘vice’ and exploitation (a position firmly in keeping with the Queensland government’s policies of segregation), promoted ‘Christian marriages between Aboriginal couples’. Once his affair with Jeannie was outed, Gribble was banished in shame, shifted 1,000 kilometres away by church authorities, and banned from ever returning. As McGrath concludes: ‘That the authoritarian ideologue Ernest yearned for intimate and sexual companionship across colonizing boundaries revealed a great crack in the many edifices that, brick by brick, he had painstakingly constructed’.

Harriett Gold ca. (Wikimedia Commons)One of the most telling aspects of the relationships that McGrath narrates in Illicit Love is the crowning hypocrisy of powerful men who, when faced with a choice between adherence to the principles of racial segregation they had advocated in public and satisfying their longing for intimacy, swiftly chose the latter course. McGrath tells the story of the Anglican missionary Ernest Gribble’s ‘illicit’ relationship with Jeannie, a Yarrabah woman with whom he fathered a child in 1908 during his tenure at Yarrabah Aboriginal Mission near Cairns. Gribble, who regularly preached that such unions were little more than ‘vice’ and exploitation (a position firmly in keeping with the Queensland government’s policies of segregation), promoted ‘Christian marriages between Aboriginal couples’. Once his affair with Jeannie was outed, Gribble was banished in shame, shifted 1,000 kilometres away by church authorities, and banned from ever returning. As McGrath concludes: ‘That the authoritarian ideologue Ernest yearned for intimate and sexual companionship across colonizing boundaries revealed a great crack in the many edifices that, brick by brick, he had painstakingly constructed’.

Like Gribble, John Ross, chief of the ‘Cherokee nation’ and one of the authors of the ‘Cherokee Constitution’ (1827), had spoken against interracial marriage in his community. Ross, however, soon ended up transgressing his own rules when, after his Cherokee wife died, he fell in love with Mary Stapler of Wilmington, New Castle, Delaware. Remarkably, their marriage has been little explored by historians, despite the existence of a cache of correspondence between the two lovers which McGrath exploits to full effect. Given the wealth of primary material here and McGrath’s skilful use of the couple’s letters, this is one of the strongest and most gripping chapters of the book.

It is commonplace for reviewers of outstanding scholarly books to plead that they ‘deserve a wide audience’, as though readers might need more than a little shepherding. I will make the same plea for Illicit Love, a book that amply realises McGrath’s long-standing ambition to ‘write history that people want to read’.

Comments powered by CComment