- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

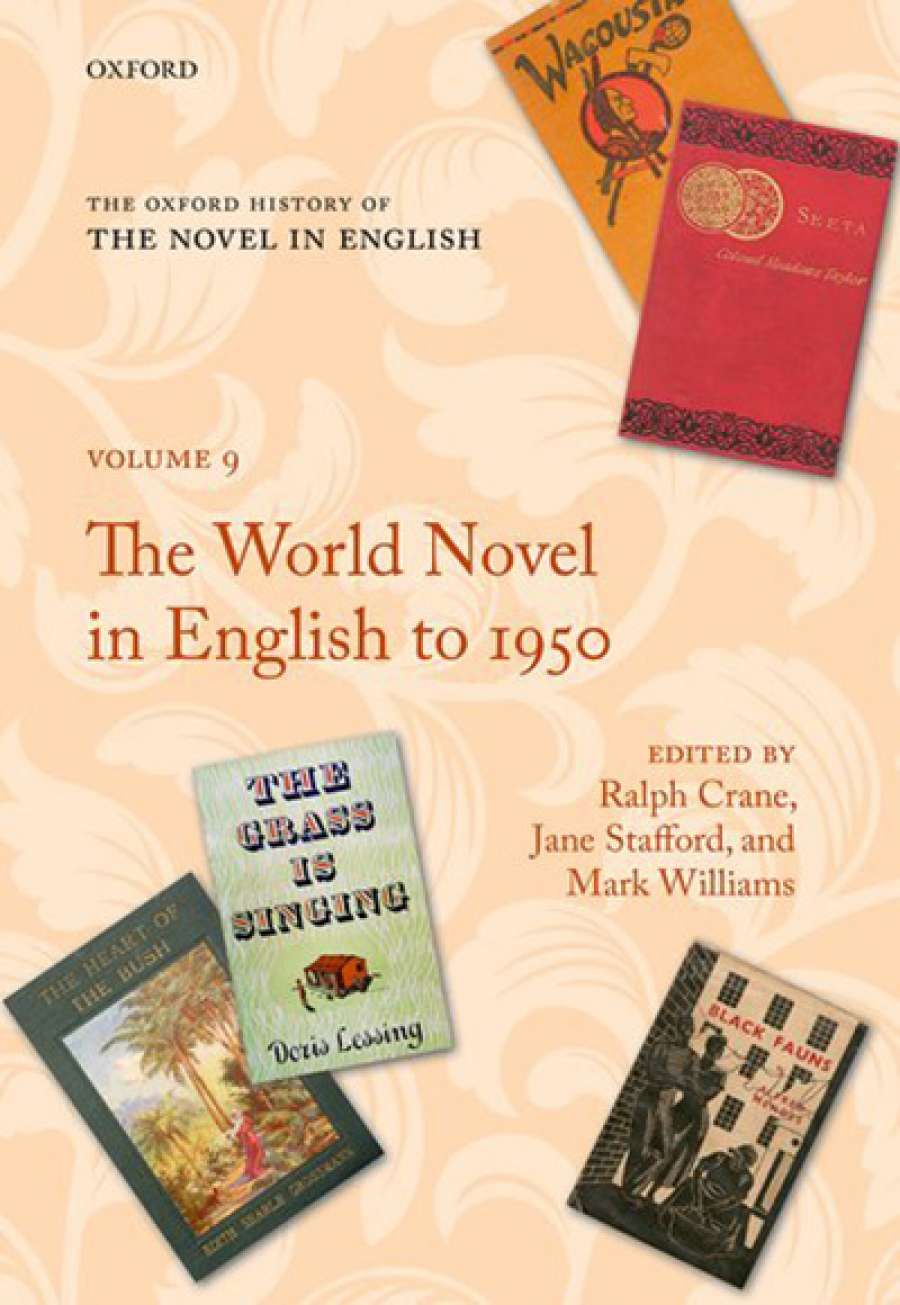

- Custom Article Title: Paul Giles reviews 'The Oxford History of the Novel in English: Volume 9: The world novel in English to 1950' edited by Ralph Crane, Jane Stafford, and Mark Williams

- Book 1 Title: The Oxford History of the Novel in English

- Book 1 Subtitle: Volume 9: The world novel in English to 1950

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $160 hb, 501 pp, 9780199609932

The first section in The World Novel, entitled ‘Literary Production’, includes individual chapters on ‘Book History’ and ‘Colonial Editions’; this sets the overall tone for the work, which is generally descriptive and impressive more for breadth than depth. The book does cover an enormous range of material, and it contains many nuggets of useful and (to me, at least) unexpected information, such as the commentary in Ralph Crane’s chapter on ‘The Anglo-Indian Novel to 1947’ on popular Victorian novelist Philip Meadows Taylor and on how Matthew Arnold’s brother, William Delafield Arnold, published in 1853 under the pseudonym ‘Punjabee’, a novel entitled Oakfield, a fictionalised account of Anglo-Indian society. On the other hand, there is very little extended critical commentary on any of these works, and within the critical surveys that make up the bulk of this volume, discussions of major writers often seem brief and reductive. Xavier Herbert, for example, is dispatched in six lines and Eleanor Dark in one paragraph, while the analysis of figures such as Joseph Conrad, Herman Melville, and D.H. Lawrence, whose fiction encompasses many different parts of the world, often seems quite ‘retro’ in its orientation.

The editors were clearly aware of the difficulties involved in trying to balance their book’s multiple coordinates, and they have sought deliberately to counterpoint these more generalised overviews with chapters towards the end that focus more specifically on ‘Individual Voices’ and ‘Critical Contexts’. There are some particularly insightful contributions in these latter sections, particularly Harry Ricketts’s informative and well-written piece on ‘The Persistence of Kim’ and the politics of Rudyard Kipling’s literary reputation more generally. The other individual voices granted the privilege of a separate chapter are Mulk Raj Anand (India), Sara Jeannette Duncan (Canada), Olive Schreiner (South Africa), Marcus Clarke (Australia), Robin Hyde (New Zealand), and G.V. Desani (India), a selection that does seem somewhat arbitrary.

Rudyard Kipling, 1892 (Bourne & Shepherd, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, via Wikimedia Commons)It is noteworthy that the novel since 1950 has been granted no less than three separate volumes in this Oxford series – one on the novel in ‘South and South-East Asia’, another on its life ‘in Africa and the Caribbean’, and a third on ‘Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the South Pacific’. Such largesse emphasises how the task of compression imposed upon the editors of this ninth volume must have been severe indeed. But they would have faced a further dilemma, involving the definition of the ‘novel’ itself, a generic form that has always thrived on impure associations, not only with romance – Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1624) is cited as an influence in the chapter on Oceania – but also with popular journalism and pamphleteering, going back to the days of Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift. Again, the editors take a pragmatic line here, declaring in their introduction their intention to omit authors such as Katherine Mansfield, ‘whose work is entirely within the short story genre ... except where they contribute to the development of larger patterns within the novel’. But in Mansfield’s case, this is almost always, and her story ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’ is duly (and sympathetically) treated in Angela Smith’s essay on ‘Colonial Modernists’. The law of genre, as Jacques Derrida sardonically remarked, is a law intended only to be broken.

Rudyard Kipling, 1892 (Bourne & Shepherd, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, via Wikimedia Commons)It is noteworthy that the novel since 1950 has been granted no less than three separate volumes in this Oxford series – one on the novel in ‘South and South-East Asia’, another on its life ‘in Africa and the Caribbean’, and a third on ‘Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the South Pacific’. Such largesse emphasises how the task of compression imposed upon the editors of this ninth volume must have been severe indeed. But they would have faced a further dilemma, involving the definition of the ‘novel’ itself, a generic form that has always thrived on impure associations, not only with romance – Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1624) is cited as an influence in the chapter on Oceania – but also with popular journalism and pamphleteering, going back to the days of Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift. Again, the editors take a pragmatic line here, declaring in their introduction their intention to omit authors such as Katherine Mansfield, ‘whose work is entirely within the short story genre ... except where they contribute to the development of larger patterns within the novel’. But in Mansfield’s case, this is almost always, and her story ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’ is duly (and sympathetically) treated in Angela Smith’s essay on ‘Colonial Modernists’. The law of genre, as Jacques Derrida sardonically remarked, is a law intended only to be broken.

This volume as a whole, then, might be seen as something of a critical hotchpotch, but this also comprises its strength. Because of its general accessibility and the huge amount of material covered by its distinguished contributors, this book will undoubtedly be useful for undergraduates or even high-school students seeking background information on the global tentacles of English-language fiction in the nineteenth and earlier part of the twentieth century. Oxford University Press, like its Cambridge counterpart, is now heavily committed for financial reasons to encyclopedic projects of this kind, figuring that they can exploit the gravitas of their brand name to sell their merchandise to reference libraries, and in a pragmatic sense readers are more likely to make use of this work by seeking out individual chapters rather than reading it from cover to cover.

Overall, this book contributes impressively to a broader sense of how Australasian literature has intersected over a long period of time with narratives that have circulated around the world. It does not, though, have much to say about the status of world literature as what Franco Moretti called ‘a problem’ rather than ‘a subject’, a conundrum turning upon complex relationships between centre and margin whose stress points can never entirely be resolved through merely expanding the circumference of global coverage.

Comments powered by CComment